Melodie Jackson grew up in a predominantly Black community in Mississippi and did not become fully aware of racial and social justice issues within the Church and in the United States until she served a full-time mission in Brazil and attended BYU in Utah. In response to the societal turmoil over the high-profile murders of multiple Black people in 2020, she launched the “Black Lives Matter To Christ” Facebook page. She hosts devotionals for Black members of the Church to share their experiences of racism and the comfort they find in Jesus Christ.

What is the background of how you started working on social justice issues?

I’ve talked about this a lot recently – my journey into consciousness and being aware of racial injustice in America. I was aware of these things in high school. Black History Month was my favorite month, I was on a Black history quiz-bowl tournament team, all my poetry…I went back and read my poetry and it was all centered in the experiences of Black lives. Growing up, I just wasn’t aware of racial problems in the world. My grandmother told me stories but in my mind, they were very particular to Mississippi. I had no idea of institutional systemic things.

I was surrounded by so much Blackness – my family, my neighborhood, my school – that church was literally the only white space I occupied. Somehow, I separated church from the world. It didn’t really occur to me that the racial things I noticed in the world also could happen at church. It wasn’t even a possibility in my mind that those two things collided.

As I’ve gotten the language and vision to recognize racism in the world when I look back over my youth, there are things that didn’t really occur to me then, but I notice now. Why was my family the only Black family to consistently attend the ward? Why did my grandmother, who loved-loved-loved going to church and going to Relief Society, stop going to Relief Society one Sunday, but would make us stay and come pick us up afterward? Why were there not more Black people in church?

When did that perception of the Church being a white space shift for you?

Melodie Jackson, Missionary

My mission definitely awakened the idea of racial injustice, especially within the Church. Having a Black mission president blew my mind, but not until I thought about it. I grew up in Mississippi and I’d only seen three Black priesthood leaders and just a few Black families in the entire stake. Mississippi is 50 or 60 percent Black. On my mission, I had Black bishops and Black stake presidents. I saw tons of other Black missionaries. I was the only one from the United States, which is very telling. There were Black missionaries from Brazil, Black missionaries from Europe, Black missionaries from Continental Africa. Wait – this is not the church I experienced in Mississippi.

I’ve heard that the Church situation in Brazil was the tipping point for removing the ban on Black people being ordained to the priesthood and attending the temple. The rule was “not one ounce of Black blood,” and they got to Brazil where this person was a quarter and that person an eighth, and what were they going to do about that. Is that true?

That’s true. Shout-out to my Ph.D. research that hopefully will cover that more in-depth. It started with President David O. McKay. McKay, in terms of pre-Kimball prophets, had this question because he had gone to different countries. His perception of race relations was vastly different than previous prophets before him because he had gone to New Zealand and different places in Polynesia and had formed a relationship with these people. So he came back to America and then became the prophet, and started having questions about the priesthood ban, and started thinking about Brazil. In 1978, the Sao Paulo Temple was built.

So that was the catalyst – the Sao Paulo Temple.

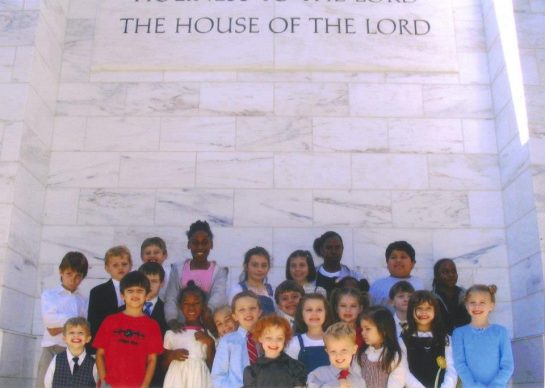

Primary children at the Temple

There were Black members building the temple and paying their tithing, and putting in the effort to see this temple built. They had this conflict of interest – these people were very faithful and working really hard. But they couldn’t go into the temple.

Race relations in Brazil are very different from race relations in America. In the US, there’s the legacy of the one-drop rule. For Brazil, you can’t really do such a sharp contrast because they didn’t have laws that segregated Black people and white people like America did, so there was a lot of intermixing. So the Church leaders had questions of what to do with that – how do they test Blackness? David O. McKay had that question a lot – is it one fifth, one-tenth, one percent – which is crazy because you can’t really measure race.

Going on my mission to Brazil and seeing these Black leaders – not just in priesthood positions but as Relief Society presidents and Sunday School teachers, my mission president’s wife was a Black woman … A majority of the members in the areas in which I served – they looked Black. So it was unbelievable to me that there was a priesthood and temple ban. It completely shifted how I viewed Black bodies in the Church as a possibility and could be the norm. I know that Brazil isn’t the perfect place to look at race relations – if you look at the highest leaders of the Church in Brazil, they’re all white and of European descent. But my mission completely opened my eyes and showed me that Black people occupy a large space in this Church. They have contributed significantly to the history of the Church, the history of temples, the history of community worshipping, and just building the Church. If you took out the members in Brazil, the membership numbers would significantly decrease.

When you came home from Brazil, you went to BYU. How did you get involved with social justice issues and classes there?

I did my freshman year at BYU before my mission, and I thought it was this utopia. BYU was the greatest place ever! My roommates were so awesome! I loved my experience.

Then I got this lens, and coming back to BYU was so bizarre. I came back from my mission in April 2016 – that was the summer that Philando Castile was murdered in Minnesota and Alton Sterling was murdered in Louisiana. That also was a shock to my system. A friend reached out to me because she saw some of the things I was posting on Facebook, trying to articulate these feelings that I didn’t really have the language to say yet. She said, “I’m a teacher’s assistant for a sociology class, Race and Ethnicity. You should take it.” That class and my mission completely awakened something in me – things that I’d noticed as a child and youth but I didn’t know how to explain or understand it. Those two things gave me the language and the eyes to see things that were going on in the world and in the Church.

Once I started recognizing things and became more vocal, there was immediate pushback. People would question my testimony or immediately shut down whatever I was saying. I’m grateful to certain professors who gave me space and said, “No, we’re going to listen to everyone. Everyone can express their opinions and especially their lived experience without there being immediate rejection.” In that first sociology class, there was a power struggle because there was this group of white men in the back – why you even here? Every single class period – the professor was a Black man – we would learn something and that group in the back would tell him he’s wrong and invalidate his experience.

My religion classes were really the power struggle. I was changing how I perceived the Church, how I perceived doctrine, how I perceived leaders, and I was very vocal about that. There was immediate fear. In one of my classes, we were talking about prophets and I raised my hand – “We should probably also discuss that prophets aren’t perfect and they make mistakes. Like the priesthood ban – that was a mistake, that was not of God.” A student waited for me after class to tell me how wrong I was, and that Black people are cursed, and until I showed him some document by recent leaders that the words of Brigham Young were incorrect, he would not change his mind. As if I served him.

I felt so very uncomfortable all the time. I was traveling this line of hyper-visibility and invisibility. Hyper-visibility because I’m Black and there were only about 300 Black students out of 33,000 students at BYU. Invisible by always having my thoughts invalidated and always having my experience questioned.

What did you do for a support network at BYU to help you deal with that?

I took these classes and was finding Black friends, and we started going to the Black Student Union. Someone asked me if I’d ever been to the Genesis Group – it gave me the community that I needed so badly within the Church. It was a really beautiful experience to worship with other Black people with a Gospel choir, with hand-clapping, with preaching. It just felt like home. It felt like a safe space. It felt so good to have a shared experience with Black people in the Church and discuss what it meant to have a Black body in this church and still have our testimonies, while struggling with the conflict of Blackness within our theology and also within our culture as a church.

I’ve heard of the Genesis Group but never really understood it. The way you describe it sounds like a Spanish Ward in such-and-such stake, except it’s not Spanish or another language, it’s for Black people.

BYU students with Darius Gray

I wish it was that. It was started in 1972, six years before the priesthood ban was lifted. Darius Gray and a couple of others were baptized into the Church and they were struggling because there weren’t a lot of Black people. Also, they couldn’t hold the priesthood or go to the temple. They were gathering together mostly as a support group, processing what it meant to be in this Church and not be a full member. So they approached President Hinckley and said, “Hey, Black people are struggling in the Church and we need to do something about it or they’re going to keep leaving. This is our church too and we need a space where we feel supported.” So the general authorities came up with the Genesis group. It’s a gathering space for Black people. It’s not a ward because it meets only once a month. It’s more of a devotional or fireside type atmosphere. There’s a presidency and they have activities. There’s a Relief Society and Primary and Young Women, but it’s not officially recognized as a ward.

So that helped you with extra support at BYU. Tell me about the Black Student Union [BSU] on campus – was it already a group or did you help form that?

I could never take credit for that. It was already a group. It was small when I first started going, and last year, it was 60 or 70 people. I became the vice president so I was in charge of different activities every month to help Black students at BYU. It was really a safe space where we could talk about what it meant to be Black at BYU. We could organize and plan – let’s see if we could push this department to have a panel about this, or let’s see if we can do something about this, have a protest, petition the school to have a required class about race. Stuff like that. It was really a cool space where we could come together and talk about our different experiences.

Even being Black, the experience of Black people from the US were so very different from the experience of Black people from continental Africa. So very different! We often clashed, because they just had a different experience with racism and white supremacy and whiteness. Colonialism is very different from what we have experienced in America as Black people. Our experiences were different but it was a really cool space to come and have those conflicts and see how we could join together in getting so many things done at BYU. The people who came before us – we stood at their feet because they had done so much. There is still so much to be done at BYU and the Black Student Union is a gathering space to come up with ideas to change things.

When you left BYU, did you feel like you had resolved anything, or was it – good luck, see ya later!

When I left BYU, I felt relieved. It was not an academically challenging place for me but it was so taxing on my spirit and mental health. I definitely know that all the work I did there as an organizer and an activist – it was never really for myself but for the people that come behind me. It’s been cool and beautiful to see the little seeds that I planted – people at BYU now are watering those seeds.

Bryan Stevenson came to BYU – he wrote the book Just Mercy and created an organization that frees innocent people on death row, the Equal Justice Initiative. He also started a monument in Birmingham Alabama to commemorate lynchings in America – the first memorial to those victims in a public space, our public memory. He came to BYU and talked about his book and the memorial.

I had already been thinking about building names on campus because I was on a committee in Provo to rename Squaw Peak, because it’s a derogatory word for an indigenous woman. I was thinking about places and spaces and the names that we give them, and how that translates to violence and affects people in the community. I am not ashamed about this but I completely fabricated the question I submitted to ask Stevenson because I knew they wouldn’t approve my real question. I said, “I see the work that you’ve done in Birmingham with public memory, and calling people to be accountable for the way we remember things. How can we translate that here at BYU where our school is named after a man who said racist things, our buildings – Abraham Smoot was a slave owner, leaders have said racist things, have been anti-Civil Rights, anti-Black.” He was so happy I asked that question because he had done research about BYU and he was waiting for someone to bring that up!

After that, I formed a committee of professors – do we try to rename the buildings, or do we add a plaque next to the building that accounts for the true history of these people for which these buildings are named. After I left BYU, two of my really close friends partnered with the NAACP to push the petition and movement forward in trying to rename buildings, or at least offer some accountable history that these men participated in and perpetuated anti-Blackness. It’s been really cool to see the work being continued by Black students there now. The BSU is amazing – the new presidency is doing things that I never would have thought of.

Since you graduated from BYU, you’ve started the “Black Lives Matter to Christ” Facebook page. How did that get into your brain and off the ground?

I’d been doing different organizing things before Black Lives Matter to Christ, especially within the Church. When the Church did the Be One event in 2018 to commemorate the 40th anniversary of lifting the priesthood ban, Elder Gary E. Stevenson really wanted to do something with the Black young single adults to make this experience personal, so he formed a committee and I was on that committee. We planned a really cool event after the Be One broadcast for three of the Apostles to speak directly with Black people.

We kept the Be One YSA group going at BYU. We had Black Family Home Evenings (FHE) – Black students were not going to FHEs because they didn’t feel comfortable for various reasons. We had firesides and devotionals for Black students. We had what we called a black-out, which was my absolute favorite thing. Any time one of us spoke in sacrament meeting or taught a lesson at church, all of us would go to their ward and “black-out” their ward, to show that Black people exist in the Church. There would be 30 or 40 Black people going to one ward to support one person giving a talk.

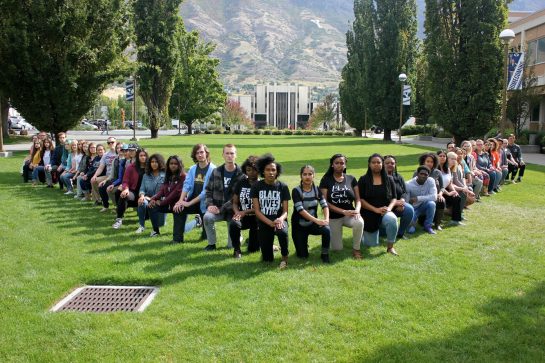

Melodie Jackson and students taking a knee at BYU

We were doing things and organizing around social justice in the Church. But when I left BYU, I wanted to do something for myself. With COVID happening, and then the world blew up from the deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd, there’s always this yearning from a lot of Black people in the Church to want words of comfort from our leaders and it never comes. It almost never comes. So I thought, since we never get these words, let me just follow the example of the Black LDS Legacy Conference – I don’t know if you know about that.

I don’t – please elaborate!

They are an amazing group of Black women who have a conference every year at the Washington DC Temple Visitors Center. It’s an academic and cultural conference centering on the experience of Black people. People come and read their research. People come who are doing different cool things in the Church – art, writing, anything of that nature.

The people who formed it are my mentors. All these different women that I look up to – Janan Graham-Russell, LaShawn Williams, and others – they were already organizing. They are the ones who came up with the Be One event and the Church leaders took it over, but they were the ones who said we’re going to do something because 40 years is a significant number in the scriptures. Everything I learned about organizing within the Church came from this group of women.

That’s awesome that you have so many mentors. Back to Black Lives Matter To Christ…

I wanted to do something because Black people need comfort and peace right now, and I think the gospel brings a lot of that. I prayed about it and reached out to a lot of people who I felt were in a lot of pain and probably could find some peace in expressing that pain and building community. They all agreed to do it – we’ve done devotionals twice so far, and it was a really amazing experience.

I’m trying to decide if I want to do a devotional every other month or every three months. So we’ll see how it goes. I want to expand that page so much – I think I have to allow other people to participate, but it’s my baby and I don’t want to let it go. But that page could be so amazing, like the letter-writing campaign we had.

It was in June (2020) and June seems like two years ago. We did a letter-writing campaign to the Twelve Apostles – I invited Black people to write to them about their experiences in the Church. It was initially intended for just Black people to tell their experiences because I think the Apostles are so far removed from those experiences. But then it turned into white members wanting to tell their experiences and how they’ve seen instances of racism, like with children who were interracially adopted. When we do it again, I feel like picking a specific Apostle and saying we’re all going to send letters by this date. I think doing a targeted campaign like that – telling them why Black lives matter, and why Black lives matter to Christ in this Church – could be a really important thing.

How do you see this going forward?

The future is to be able to share the experiences and stories of more Black people, so that other Black people can find community, and share the work that Black people are doing because they are doing so many amazing things in this Church!

This past devotional, I wanted to do a giveaway but I ran out of time. Melissa Kamba has amazing artwork that is so mind-blowing and I think she’s going to be pivotal in how we imagine Blacks in the Church. Fatimah Salleh’s book, The Book of Mormon for the Least of These, completely changed my life, my theology. It’s the Book of Mormon through a social justice lens, and it’s amazing! So amazing! Her research and her work … for a lot of people in the Church, social justice and the gospel seem like conflicting ideas. It’s totally not! People make you think that they’re conflicting ideas, but they’re not! Some of my friends are doing just really cool things.

Melodie Jackson

At the end of the day, I’m trying to claim space – this is my church too. But at what point does that become exhausting and is it even worth it? I’m in this constant state of conflict, trying to figure out if I should be here – wait, you should be here because there are so many Black people for you, that fought for you to be here, and are doing so much work to make this a space for you. But I personally think that the Church has to go through a process of atonement because it’s done so much harm to so many people. The Church hasn’t really dealt with this history of anti-Blackness, the theology of anti-Blackness in a way that offers salvation for the Church.

The Gospel of Jesus Christ is so beautiful and so liberating and so expansive. I’m working on a poem right now – why do we make God so small? I went to pray one night and I couldn’t even see God because we’ve made Him so small – or Them. Why is it even Him? God is so much bigger than what we’ve conceptualized and theorized God to be. Our culture shrinks God so much, but really, I think our theology allows God to be expansive.

We are always talking about preparing our Church for Christ to receive, but are we working on that? We need to be actively trying to allow the Church to be as good as the Church can be.

At A Glance

Age: 25

Location: Vicksburg, MS

Occupation: Graduate Student

Convert to Church?: 2009

Education: BYU, B.A. (American Studies), University of Maryland (American Studies) PhD (Current)

Languages Spoken at Home: English

Favorite Hymn: Total Praise

Interview Produced By: Trina Caudle