April 2010, Alpine, UT

In February 2001, Marilynn Clark visited Africa on a humanitarian expedition and the trip gave her a vision for her future work. She has since started Inside Out Learning, a system of teaching that introduces critical thinking, creativity, and moral perspectives to African school children. Marilynn discusses how humility and her experience in Church callings have made IOL possible.

How did you initially become interested in helping the people of Africa?

I like to travel but my husband doesn’t, so when I have an opportunity to go somewhere, I jump at the chance. Years ago, a friend called and said she was going on a humanitarian expedition to Africa. Africa was a place I hadn’t visited and it sounded exciting, so I went. That was February 2001. We visited schools, took school supplies, and enjoyed a cultural experience. I don’t think we did much to help the people, but for me it was a life-changing experience. I had never been to a third-world country. I wasn’t aware of the poverty that existed, and I was so shocked by the tragedy, the desperate situation that much of Africa’s population faces.

On one of my first trips to Africa, I traveled to Uganda and met a man who wanted to go to medical school. I agreed to help him financially, but I didn’t have extra discretionary funds, so I had to make the money I had agreed to send him. So I started baking. I have a couple of neighbors and friends who help me, and we bake a couple times a month, sometimes once a week. On a big day, we go through 100 pounds of flour. It’s a big baking day. We’ve funded this student for three years. He has two more years before graduating.

It’s a community effort. All of my neighbors buy my rolls and bread. They pay more than they would at the grocery store. I hesitate to talk about this because it’s not just me. If it were, there would be nothing. Success has come from everyone contributing their piece.

What is Inside Out Learning and how did your initial experience lead you to develop the program?

After my initial trip to Africa, I decided I had to do something that would truly make a difference. So I continued going back, usually once a year, and each time I tried to learn for myself what that thing would be that could make a difference. Each trip I gathered more pieces of the puzzle and thought about what I would ultimately do to really make a difference in Africa. Instead of putting on Band-Aids, I wanted to get to the root cause of the poverty.

After a series of discoveries, I knew there was something about Africa’s educational system that wasn’t preparing people to face life, and solving this problem is where I ultimately decided to focus my energies.

Many Africans are well educated, but they can’t seem to change the economy. Africa has a 70 percent unemployment rate. The people aren’t lazy, and they have ability. But there is a missing link between the education of the work force and their productivity.

Most African schools use the rote teaching method that focuses on memorization, so creative children are often eliminated from the educational process. This led me to think about how teachers were working with children in the classroom. In addition, much of Africa faces moral problems associated with the AIDS pandemic. The concept of the family is broken. The people have lost their moral compass.

Knowing all of this, I began working with a group of American teachers in 2005 to develop Inside Out Learning (IOL), a system of teaching that focuses on three things: 1) critical thinking, 2) creativity, and 3) moral values.

IOL is based on the premise that all people are endowed with skills necessary to survive and thrive in this world. The program does not teach an academic curriculum but provides support and life skills to fully empower pupils to achieve their own greatness. The goal of IOL is to give African children, through their teachers, the knowledge necessary to discover solutions to life’s fundamental challenges. IOL gives people tools to solve their own problems. Our team can’t solve the people’s problems for them.

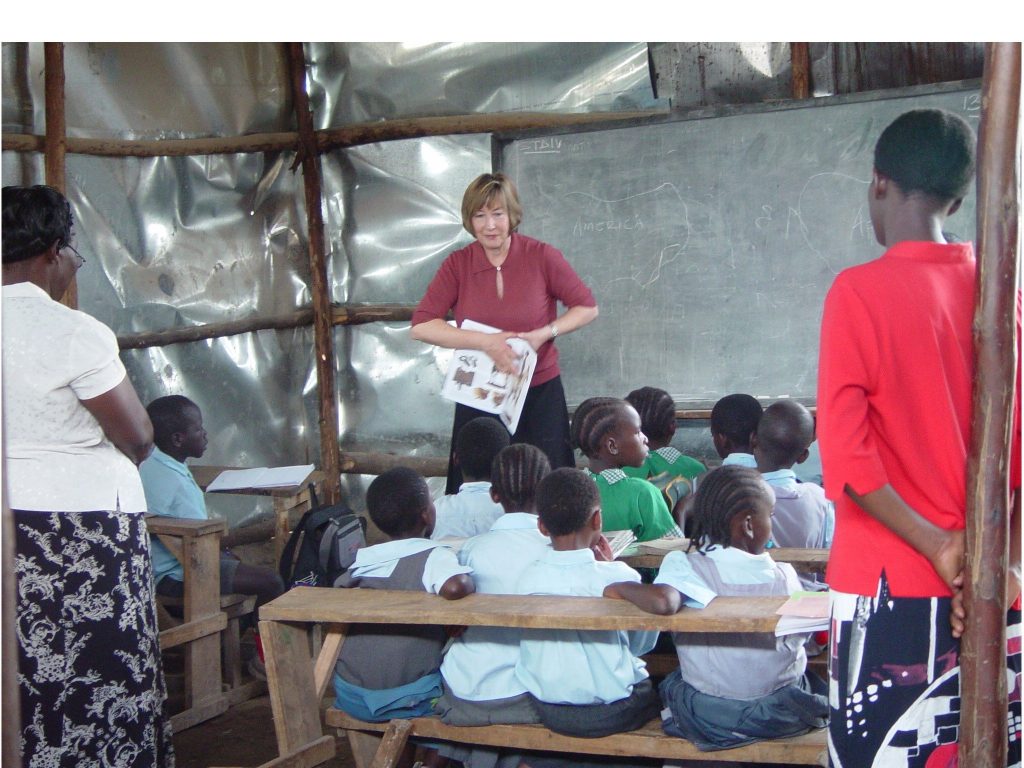

The formula for our success is that IOL allows Africans to teach Africans. We are introduced as support to teachers. Americans are not coming in pushing what they think is best. We don’t bring curriculum; we bring ideas. Teachers use their own curriculum, their own books. We just teach them how to be more effective in the classroom. We teach them different activities. We use music, inquiry-based learning. We teach how to ask questions, how to help a student who has questions, how to work as a team.

How do the IOL specifics work to improve the classroom environment and ultimately help the people change their lives?

The chance to talk about God in Africa’s public schools is wonderful. The IOL team begins training on the premise that if God created the world and everything in it—and gave people dominion over all things—He must have provided the necessary things to live in this existence. IOL aims to help the teacher understand that all children have great worth. It’s up to the teacher to help the child discover what’s already there.

In areas where we’ve worked, there are about 80 students per teacher, so teachers use very strict discipline that includes fear and intimidation. The students are very afraid of the teacher. It isn’t a healthy learning environment because the children are so afraid they’re going to give the wrong answer that they only think about having one right answer, the answer the teacher wants. Because of this, it’s obvious what happens when students integrate into society. They give up.

To help change that environment, we use a music technique in the morning to break down barriers between the students and the teacher. The teachers have been really receptive to the technique and asked how they can use music throughout the curriculum, so we brought a music specialist to Africa. She was fabulous.

Just as I was introduced to our music specialist, I’ve been introduced to all sorts of people along the way with special skills in areas like literature, inquiry based learning, and math. As I’ve been introduced to these experts, we’ve kept building the program.

How receptive have the teachers and students been to IOL?

We first introduced the program in February 2007, and the people have been very receptive. To this point, we’ve trained teachers at eighteen schools. That’s 144 teachers. About 8,000 students have received the training through their teachers.

Since that time, we’ve done research and development to see if what we’re doing is working. The results were very positive, so we’re going to train the remaining teachers in the tested district. When we’re done, there will be 24,000 students under the direction of IOL.

During the evaluation process, we met an African who received a PhD in education from BYU. He is now our on-the-ground director for Uganda. Beginning this April, we also have an organization, World Joy, paying for three of our African IOL instructors to conduct a five-day training seminar in Ghana. So we have three sites: Kenya, Uganda, and Ghana. Our program is continuing to grow, and we’re adjusting to meet the needs of the people, particularly in establishing that moral compass, those moral values.

What’s your measuring stick for success?

Once we established six to nine months of actual classroom experience, we knew we needed to measure our efforts. It’s easy to measure test scores, but we needed to measure something non-tangible.

The process of developing IOL has been amazing because every time we’ve needed something, the expertise has become available. In this case, a friend of mine who wanted to get involved with IOL happened to have a sister who worked as a marketing executive for Proctor and Gamble. She knows how to develop measurement models on a professional level and she created a questionnaire evaluation for teachers and those who had been trained with IOL methods. Our African director in Kenya also conducted personal interviews. Using these two surveys, 104 teachers were analyzed. The evaluation forms were then computed using a measurement evaluation created especially for IOL.

Results show teachers are enjoying teaching more than before. Students really want to come to school. When children choose whether to stay home and look for food or come to school, they’re choosing to come to school, which is a positive result.

We also recognized areas where we need to improve, mostly with follow up. Teachers want to know where they can find more information about IOL teaching methods. They want additional training, so we’re now putting together a mentoring program to link African teachers.

We’re interested in test scores, too. Some schools show scores are up; some schools show scores are about even. But it’s too early to have any clear data showing whether or not our work is affecting test scores.

Continuing improvement is part of the process. We will continue to test and measure, find our weak areas and improve.

How have you funded IOL?

IOL has been financed with personal funds. A few individuals have helped fund our website and trainings, but it’s hard to get people to contribute financially when it’s just ideas. We had to get the measurements. Now that we’ve got concrete data to show results, I’m hoping we can raise funds to complete additional training seminars.

The long-term plan is to be sustainable, and we’re getting close. Once we have the product and people recognize it is worthwhile, they will hopefully pay our African team to conduct trainings. I think we are about six months to a year from that goal.

What prepared you for this work? Where did you find the inspiration for the ideas and the courage to implement them?

People have been surprised when they see my lack of credentials. I’m not a teacher. I don’t have a background in education. I just had a feeling there was something missing in the way Africans were educated. It didn’t relate to what I saw in their work ethic, their wonderful ability, and the problems they face in society.

I felt I understood the problem. I needed people to help with the solution. That’s been the amazing thing. People, experts who have the skills, have come forward. I’ve always felt like the process of developing IOL was divinely orchestrated. This was something that needed to happen. The Lord was opening a way to gather these wonderful Africans and help them recognize who they are. That was the missing link. They had forgotten who they are. My mission was helping them understand that they have what they need. They don’t have to be dependent on someone else to help them. A welfare state destroys people’s confidence. It causes people to think somebody should help solve their problems and they forget to turn to that inner strength, that inner belief that with God’s help, anything is possible.

I can now see that my experience in the Church prepared me for this work in Africa. I’m doing what I’d do in a Church calling and expanding it onto a bigger field. The network of Church members has also been key. Muslims and Christians work with IOL, and they all benefit the program. However, it’s the association of Church members that have played a major role in IOL’s success. We have an automatic network throughout the world. It’s created a linking of people who have a desire to do something to benefit others.

I think the only thing I can offer is realizing I don’t know anything, and I rely on the Lord. The only thing I have brought to this process is the humility to say, I don’t know exactly what to do, but I care deeply and will follow through on a prompting. The Lord must think, “Oh that poor dear, she’s worrying about this so much and trying so hard, let’s give her a little help. She’s never going to figure it out on her own, that’s for sure. So we’ll put the right people in her path.”

The evolution of IOL is nothing short of a miracle. There are so many stories about the people who have come forward. It would take a very hard heart not to recognize the hand of the Lord in this process. It’s truly inspired. Surely the Lord could find someone better than me. And He does. If you’re sincere, the Lord magnifies your efforts. There’s no question about that.

People should proceed with whatever work shows up on their path. It doesn’t have to be in Africa. It can be next door. All of us have little promptings. Don’t turn your back on them.

At A Glance

Marilynn Clark

Location: Alpine, UT

Location: Alpine, UT

Age: 62

Marital status: Married 43 years

Children: Three daughters (35, 32, and 30)

Occupation: Homemaker

Schools Attended: Ricks College, Idaho State University

Languages Spoken at Home: English

Favorite Hymn: “How Great Thou Art”

Current Church Calling: Relief Society Meeting Coordinator

On the Web: Inside Out Learning www.iolinternational.org

Interview by Melissa Hardy. Photos by Justin Hackworth.

At A Glance