Jill Mulvay Derr began working at the Church‘s history department in 1973 as an intern, compiling the poetry of Eliza R. Snow. She spent her career there and at Brigham Young University studying and writing about the history of the Relief Society and its leaders. She participated in writing and editing multiple books about Latter-day Saint women, culminating in the 2016 publication of The First Fifty Years of Relief Society: Key Documents in Latter-day Saint Women’s History.

Could you tell us a little about yourself?

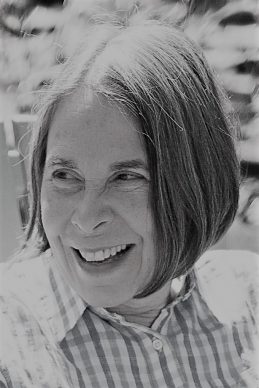

I grew up in Salt Lake City with hard-working, loving parents, known for their generosity. They were not active Latter-day Saints. Both came from pioneer families but my mother’s ancestors became hostile toward the Latter-day Saints. My dad went inactive when he joined the Navy at age 17. Still, they decided that it would be best if their children attended Church and had Latter-day Saint associates. So my three siblings and I went to Primary and Young Women, and the four of us were baptized around age eight. Our parents supported us in Church activities even though they themselves never entered into Church activity.

I attended the University of Utah, then went to the Harvard Graduate School of Education for a Master of Arts in Teaching degree. I taught for two years in the Boston public schools, then returned to Utah. I started working at the Church Historical Department in 1973. My husband Brooke and I married in 1977. He brought three children to the marriage and we had a child of our own, so we have a family of four children. Our children are now grown and we have eleven grandchildren.

We had two wonderful experiences abroad. My husband taught at the University of Utah, and in 1985, he took an appointment at a business school in France, so we lived there for eight months. We lived in Europe again from 1989 to 1991, this time in Switzerland where he taught at a different business school.

Brooke and I are retired now and we served a mission in Frankfurt Germany, 2012-13.

How did you begin focusing on women in Church history?

I was in Boston when Claudia Bushman and Laurel Ulrich and others sponsored a lecture in the early months of 1973 that featured Maureen Ursenbach [Beecher] talking about Eliza R. Snow. I attended that lecture and was fascinated. I knew nothing about Eliza R. Snow. I couldn’t believe that Maureen had that kind of information. I talked to her afterward; she told me that she was doing her research in the Church’s new History Division under the direction of Leonard Arrington, the newly appointed Church Historian.

That spring, I returned to Salt Lake. I had planned to get a teaching job but couldn’t find one. A friend suggested I visit Maureen at the Church Historical Department where they were sponsoring some internships. I had been making about $8000 teaching in the Boston public schools, which was a good salary for that day, and I had determined I would not accept less than that in a teaching job. Then I connected with Maureen and got this offer for an internship for $1000, and snatched it up as fast as I could.

Eliza R. Snow (1875)

My first assignment was searching for the poems of Eliza R. Snow. It was like I parachuted into a totally different world, to be engaged in research. My undergraduate work was in English with a History minor. I knew absolutely nothing about Church history. I knew nothing about women’s history. I had not been stirred or awakened by the women’s movement that was happening around me. But I was soon enmeshed in all those ideas and concepts and people.

After my internship ended, a full-time appointment in the department came through the James Moyle Oral History program and I began interviewing recent women’s leaders – LaVern Parmley who had just been released Primary General President, Belle Spafford who had recently been released as Relief Society General President, and a series of other Latter-day Saint women. So it plunged me in – I learned to swim by being dropped in the water. What could be better training than working under Leonard Arrington and Davis Bitton and James Allen and Maureen? They were great mentors.

You noted that the women’s movement of the 1970s didn’t really catch your attention, but was it connected to the Church’s focus on women’s history? Belle Spafford is known to have opposed the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), but at the same time, the Church was apparently focusing more on women in our history. How did that balance out for you within the setting of the Church Historical Department?

That’s a very interesting question. It really sets up some of the tensions of that era. One of the challenges was that the Correlation movement was in full swing. In 1970-71 especially, we see this big era of change. The Relief Society had been running Social Services, the Primary ran the Primary Children’s Hospital. Women published their own monthly magazines – the Relief Society Magazine and the Children’s Friend. Each of the three women’s organizations had its own budget and responsibilities. Through the Correlation movement, all former Church publications were terminated and replaced by the Ensign, New Era, and Friend. All of women’s major responsibilities were to be umbrella-ed under what we then called simply “the priesthood” – which at the time meant these responsibilities would be managed by men.

That was a huge change for Latter-day Saint women. It required a considerable loss of autonomy but reflected the need for the simplification and central direction that enabled internationalization and the growth of a worldwide church. Relief Societies in Utah could have bazaars and fund their projects and decorate their rooms how they wanted. In the Philippines, however, Relief Society women had no resources and no money. They could do much more by being under a ward budget.

Correlation was part of the difficult transition to becoming a global church and reaching members internationally. I think that transition has been a long time coming – a gradual move away from concern about the Wasatch Front and how things are done here, to what we can do worldwide. So today we see the immediate translation of conference talks or manuals going out to all the world at once, instead of dribbling out year by year to different communities.

But to get back to your question – there were lots of changes in the Church at the same time there were lots of changes in the world. In the world, there was emphasis on women’s equality, the Equal Rights Amendment, equal pay for equal work, advanced positions and responsibilities for working women, expanding women’s lives into the public sphere, moving beyond the private sphere. At the same time in the Church, there was new emphasis and a real focus on the home, Family Home Evening, priesthood directed homes, priesthood directed (usually male-directed) everything, and women’s responsibilities in the Church became more narrowly focused in the home.

Was this a clash? Yes, it was. It was impossible for it not to be. In doing women’s history, in looking at how Latter-day Saint women’s lives corresponded to the lives of American women, answering the questions that the feminist movement was raising as we worked on Mormon history – yes, there was considerable dissonance there. It was certainly an awakening for me.

Maureen and I started going to women’s history conferences. We could see the questions that the world was opening up – our first efforts were to answer some of those questions. We looked at public figures, we looked at famous women, we looked at women in politics, we looked at women in medicine, we looked at women in the arts…because the focus on public figures was what was happening in American women’s history right at that time.

It was a time of discovery for me. In addition, Maureen and I were part of a women’s group established in Salt Lake City in 1974 – some were women from Boston who had helped publish the 1971 pink Dialogue that addressed women’s issues. We decided to call our Salt Lake City group Retrenchment because in 1869, as Relief Societies were reorganized in Utah, they operated only on a ward basis. The women themselves developed a monthly meeting called General Retrenchment where they met across ward boundaries. So we chose that name for ourselves because we were outside the confines of our ward associations. The group is still meeting now, fifty years later. It is an amazing collection of women, and it’s wonderful.

That group was the place I worked through a lot of women’s issues such as concerns over the ERA and concerns over changing the Relief Society organization. On one hand, I was studying history, and on the other hand, I had this great exposure to these lively and intelligent women who understood political science and social work and literature and medicine and different fields that really make for a rich conversation, which, as I said, continues.

I’m seeing in my mind this group of women focused on community and learning and not necessarily being in their home all the time, which was not what the Church leaders encouraged at the time. That’s something we still have a challenge with now – many women feel that they are told that they should live a certain way, to stay home with their children. But they’re done having kids, or they don’t want kids, or they want a career and kids. So there’s tension. How did you deal with that tension in the 1970s?

I graduated from the University of Utah in 1970. It was difficult for me because most of my college friends were getting married and settling down. I opted to go to graduate school, which was unusual. I think the fact that I chose a one-year program bespeaks my ambivalence about it. I didn’t want to sign up for a long-term graduate degree. I was brave and timid at the same time. I loved my time at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. I enjoyed associating with people there. I returned to Utah without being married. So I was going to try to have a productive life in the interim, whatever happened.

I was 29 when I married, much later than most of my friends, and I continued to work. I loved my job. I had been working in women’s history for four years. In fact, before we married, I had a wonderful bishop, Craig Sudbury, who thought I should serve a mission because I was older and single. I told him I didn’t feel good about that. This wonderful man said, “I’m willing to fast and pray with you on a given day and then let’s talk again.” We talked again and I said, “I really feel that the work I’m doing is my mission.” He said, “I feel that way too.” He gave me his full support.

I felt strongly that I should marry Brooke – I was wildly in love, and he was supportive of my work. We had full custody of one of his three children, an 8-year-old son, so I went to half-time employment so I could balance my work and give part of the care to this son. Brooke was teaching at the University of Utah and as a professor, he had some flexibility. So we were able to manage that.

Jill Mulvay Derr

It was harder after a son was born to Brooke and me because in addition to having an infant we were in a custody battle over his other two children. So our family situation seemed very different from the traditional family. Those were difficult years and without the wonderful support of family, friends, and neighbors, we couldn’t have made it through. My neighbors were full-time homemakers. I never felt criticism from them – I always felt their love and support. Maybe that was easier for me because I was working for the Church, so there seemed a kind of legitimacy that other people may not have felt. I acknowledge that I was in a position of privilege.

Did I feel tension about my decisions? Of course. I think all women who work evaluate and reevaluate what they’re doing, how to balance their time, what their own health is, what kind of support is available from a husband depending on his work, or from sisters or parents or ward members. It’s a balancing act. I recall running into a friend and she asked me how I was doing. I said, “You know, life never seems to be quite in balance.” She just looked at me and said, “And it never will.” I thought that spoke to the sense of juggling, the way we’re always asking if we’ve got it just right, trying to meet the commitments to family, to work, or community service. I think for all women, it’s a balancing act.

And you’re right. The rhetoric from the Church sometimes makes us feel that we have to be the perfect mom. I think my history work helped me because of the diversity of models. It’s one thing to talk about ideals and principles. It’s another to see the diverse ways that people live them out. That was very liberating for me.

You worked for the Church your entire career. How many books did you work on? Were they years-long projects?

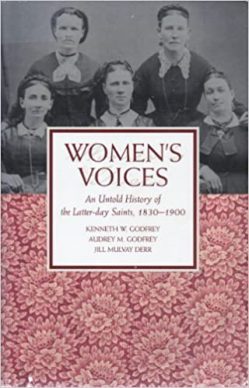

Women’s Voices: An Untold History of the Latter-day Saints

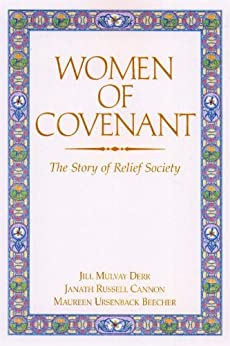

The projects all fit into the family-work-life conundrum. The first book that I worked on was in collaboration with Kenneth and Audrey Godfrey, Women’s Voices: An Untold History of the Latter-day Saints. That project started when I worked in the Church’s History Division, directed by Leonard Arrington. I stayed with the division until about 1980. After our son was born, I couldn’t balance children, writing, and commuting the forty minutes from our home in Alpine to work in Salt Lake, so I terminated my employment. But I completed the work on Women’s Voices and it was published by Deseret Book in 1982. Around 1980, I began working on Women of Covenant, the Story of Relief Society with co-author Janath Russell Cannon. That project had to go with me first to France and then to Switzerland.

By the time we came back from France, the Church History Division staff in Salt Lake had been transferred to BYU to become the Joseph Fielding Smith Institute for Church History. Since those were my colleagues, I reconnected with them in 1986 and they offered me part-time work. I remained with Smith Institute and BYU until 2005. That year, I moved back to the newly reorganized Church History Department in Salt Lake. So yes, over a span of years I was employed by the Church, but in two different places, and at three distinct periods.

The Smith Institute director, Ronald K. Esplin, not only helped me get a part-time appointment at the institute but also fully supported the Women of Covenant project which with the addition of a third author, Maureen Ursenbach Beecher, was published by Deseret Book in 1992. As part of that work, Maureen and I wanted to publish the original Nauvoo Relief Society Minutes but that took a lot of negotiating over the years. I finally came up with the idea of publishing the minutes in connection with other documents from the first fifty years of Relief Society history, so readers could see how Relief Society gradually changed, and see how the minutes were interpreted over that first half-century and better understand where Relief Society is today. Context is vitally important.

Women of Covenant: The Story of Relief Society

That project was indeed long-term and went from Smith Institute back to the Church History Department when I moved there in 2005. I had already invited Carol Madsen to help with the project and the department assigned Matt Grow and Kate Holbrook to collaborate with Carol and me. The four of us were able to finally pull the massive work together. A huge team at the Church History Department helped refine it and make the introductions and footnotes historically accurate and comprehensive. That was an important team project, and The First Fifty Years of Relief Society was published by the Church Historian’s Press in 2016 (and is included on the Gospel Library app in the Church History section).

In between, I worked with Karen Lynn Davidson on Eliza R. Snow: The Complete Poetry, published in 2009 by BYU Studies in connection with University of Utah Press. That collection of some 500 poems completed the work I’d started in 1973. Some things take a long time.

I’ve had wonderful co-authors or co-editors in everything I’ve done. I don’t claim to be an independent historian. Many fine historians work on their own, independently and without a co-author. I have generally had institutional support and worked collaboratively, and that’s been one of the great blessings of my life.

Why was there pushback to publish the Relief Society Minutes?

Really, I believe parts of those minutes should be canonized and known by every man and woman in the Church because they include some of Joseph’s most beautiful and significant teachings. Maureen Beecher and I hoped to publish them because they had not been published ever, in their entirety. The reason, to state it succinctly, is because the Nauvoo Minutes raise questions about plural marriage and about the nature and extent of women’s religious authority. Both of these subjects have been and to some degree remain controversial.

Nauvoo Relief Society minutes book

Some of Joseph’s sermons to the Relief Society were edited for publication in the 1850s. Why were they edited? When Joseph first organized and addressed the women, who themselves chose the name Female Relief Society of Nauvoo, he spoke about the authority of the new presidency—the president Emma Smith and her two counselors—to preside, but he did not explicitly clarify the limits of that authority. Emma was a strong leader whom women admired and followed. As plural marriage, introduced privately by Joseph, became a subject of public gossip and stirred controversy, Emma apparently encouraged Relief Society women to take a stand against the practice. Her claim that she had authority to oppose it is only hinted at in the minutes of the last four meetings – two held on March 9 and two on March 16 in 1844. Following Joseph’s death, she did not support the leadership of the Twelve in pursuing temple ordinances, expanding the practice of plural marriage, or moving West.

As Church historians in Utah began compiling an official history of the Church in the 1850s, they included some of Joseph’s addresses to the Relief Society, but they, with Brigham Young and the Twelve, decided to redact or edit some of Joseph’s wording to clarify the limits of women’s authority. For example, Joseph’s statement in the original minutes, “I now turn the key to you” was redacted to read, “I now turn the key in your behalf,” to make it clear that Joseph was the holder of the key, turning it to open new possibilities for women. The redacted minutes appeared in the Deseret News in the 1850s, then became part of the well-known six-volume History of the Church published by B.H. Roberts.

Though the original minutes had not been published, scholars went to the Church Archives and made their own transcripts from the microfilm. Unofficial transcripts were circulating by the 1970s and 80s. Feminist scholars began to look at the original turning of the key statement and said, “No, Joseph was giving women keys.” The wording stirred questions about women’s authority for a new generation concerned with women’s equality, responsibility, and authority. How do you deal with that? During that era, Church leaders declined to publish the original minutes. In part, they, like the earlier leaders who had redacted the minutes, seemed to be thinking, “Keys? No, no, you’re not giving keys to women. Only the presiding priesthood leaders have keys, so let’s not talk about turning keys over to women.”

Another of Joseph’s addresses in the minutes talks about moving according to the ancient priesthood and making the Relief Society a kingdom of priests. These were references to the forthcoming temple endowment and Joseph made it clear that he was using the Relief Society as a means of preparing women for the temple endowment. So that’s another consideration. We have temple-related language that general Church leaders had not seen previously and didn’t know what to do with.

On top of that, we have Joseph talking about spiritual gifts, and women healing the sick by laying on of hands. That too in the 1970s and 80s was problematic. Some scholars had already begun to address these issues, but at the time Church leaders were reluctant to speak to these questions without having more information or a better sense of the context.

That was the debate, discussion, conflict swirling around. Maureen and I tried to take on part of that in our chapters of Women of Covenant. We used examples of women healing the sick. We used Joseph’s original statement, “I now turn the key to you.” Because it was published by Deseret Book, we tried very hard to provide context and explanations that would be acceptable to Church leaders and members. Two members of the Quorum of the Twelve and Elaine Jack, Relief Society General President at the time, reviewed the manuscript before it was published. To be honest, our book did not accomplish all we’d hoped for and did not please everyone. It didn’t push things far enough for the feminists. It pushed things too far for traditional members.

Now we’re living in a period when the rhetoric has changed and there’s a new understanding about women’s authority on the part of General Authorities and General Officers. We have President Nelson talking about women and priesthood in very different terms than the 1970s. He’s talking about Relief Society responsibilities to minister. Members of women’s presidencies serve on executive councils at every level. I just celebrate all of that. I know there are people who feel that the progress isn’t sufficient, and questions of women’s authority are still sensitive. But for me who has waited fifty years to see such advances, I think it’s great.

I’m grateful for the Saints volumes that forefront women in so many ways that previous Church histories have not. A friend of mine, who is very traditional and has served as a bishop and stake president, read the first Saints volume and said in all seriousness, “I had no idea there were so many women in Church history.” We’ve always been at least half of the population!

How has studying women’s history and the Relief Society impacted your personal faith?

My studies have been a significant part of my faith. Seeing the varieties of lived religion has been of immense importance to me. It’s one thing to study principles, it’s another to see how people have lived those principles. Women’s Voices: An Untold History of the Latter-day Saints is a collection of selected excerpts from women’s diaries and letters and reminiscences. Working on that book was important to me because I was able to look at individual women and hear their voices and see their lives.

At first, I was like a kid in a candy store – give me some of Bathsheba Smith’s sense of humor! Give me some of the faith of Mary Ann Weston Maughan when her husband died from persecution in England. I wanted a bit of this or that – the courage, the bravery, the humor, the faith, the humility – I wanted a piece of each of these women. There became so many women I admired that I finally came to the conclusion, oh, I guess I will have to be myself. That was just so liberating. I couldn’t be just like this one or just like that one, or a piece of this and a piece of that. I could only be me and work it out with the Lord. That was tremendously liberating on a personal level.

I have also learned the power of the collective. I started looking at not just the Nauvoo Relief Society Minutes, but also the local minutes.

One of the first people I studied was Sarah M. Kimball, president of the 15th Ward Relief Society in Salt Lake City – what a discovery for me! These beautiful 15th Ward minutes are a story in and of themselves– of women who lived with the suspension of Relief Society in 1844, picked it up in the 1850s, saw it drop and picked it up again in 1867. I loved the spirit of initiative and enthusiasm and cooperation – these minutes tell the story of the Relief Society in the 1870s and 80s.

Salt Lake City 15th Ward Relief Society Hall

The creativity of somebody like Sarah Kimball – “Let’s build a Relief Society hall! We can do this! We can have our own meeting place. Let’s sell our homemade goods in a small cooperative store and pool our money. President Young has asked us to store grain – we can do that, we can build a granary. We have money to send to those who suffered in the Chicago Fire and we can pay for the training of a kindergarten teacher.” And her sisters in other wards demonstrated the same spirit: “We can build a hospital. We can run a newspaper – the Woman’s Exponent. We can support the suffrage movement. We can be self-sufficient. We can set up a straw weaving establishment to make hats and get the equipment for weaving stockings. We can do tailoring. We can send women to medical school.”

There’s so much energy in this period –so many things women felt they could do. It was the cooperative era in Mormon history, and it opened my eyes to the variety of things that Relief Society has done and could do. Some of those activities faded as times changed, of course, but some carried on in new ways into the 20th century, such as health care for women and children and the establishment of Social Services and the Primary Children’s Hospital. There is just so much that women have done.

Part of the conflict that I and others felt in the 1970s was that those women-led enterprises were placed under the direction of men. That was difficult. But my sense of wonder and respect for those women and their energy has remained with me.

We don’t take minutes like that anymore that I know of. Was that a product of the culture at the time? Why did we stop? How can we not lose that kind of record with the current women of the Church?

Eliza R. Snow was called by Brigham Young to reorganize the Relief Societies that had been dormant, and in 1868, she started in earnest working with individual wards. As secretary of the Female Relief Society of Nauvoo she had recorded the minutes of most of its meetings in a bound volume, and that volume remained in her possession. She did submit it briefly to the Church Historian’s Office so that excerpts could be copied from it (and redacted, as we have noted), but during her lifetime the volume remained with her. She felt a keen sense of stewardship for that minute book.

In 1868, as she began the work of reorganization, she took the volume with her from ward to ward and said, “This is the pattern for organizing a ward Relief Society, and this is the pattern for keeping minutes.” In fact, as we study some of those minutes from wards in 1868, it is evident that she is the one who set up the minute book and recorded the minutes for that ward’s first meeting. She was clear about the importance of secretaries and keeping minutes. We have in the Church Archives scores and scores of wonderful minute books. Certainly this attention to record-keeping stems from the mandate in Doctrine and Covenants 21: “There shall be a record kept among you.”

When the Young Women and Primary were set up, they too kept minutes of their meetings. Elders quorums and Seventies quorums were keeping minutes. This is part of the treasure in the archives and many of those minute books are now being digitized. So today, if you go on the Church Historian’s Press website, you can see the discourses of Eliza R. Snow pulled from women’s minutes. Of course, ward and stake minutes preserve the words of many other women who were speaking – Zina Young, Mary Isabella Horne, Emmeline B. Wells, among others, and hundreds of local women. We have a rich treasure trove of women’s words in these remarkable records.

Handwritten minutes ended in about 1913-14 when Relief Society general secretary Amy Brown Lyman and others from a new generation pushed for modernization. We then had more typewriters and standardized forms. The forms were much cleaner, briefer, and the information was much reduced. If I go to Sarah Kimball’s 15th Ward minutes from the 1870s, for example, I can see, “Sister so and so said this, Sister so and so said that this is the testimony borne by Sister so and so.” Sometimes the minutes are lengthy and detailed, sometimes not. From the 1880s, I found minutes from a ward in Huntington, Utah that tells the whole story of building the Relief Society hall including a conflict with the bishop over the hall. It’s a rich story that we have now because the secretary kept elaborate minutes of who said what, sentence by sentence. It’s just a treasure.

But you don’t find that after 1914. The forms introduced in 1914 were used until about 1970, when they began to eliminate the forms. Unfortunately, many of those records have been lost. Many have been microfilmed or digitized, but many are lost. So it does become harder in the 20th century to get that kind of intimate picture from the minutes.

More recently, the Church History Department has asked individual wards, stakes, and missions to assemble annual histories. Some of those are very rich and meaningful, some are just photographs of youth activities. My husband and I served a Church history mission in Europe for 18 months, and part of the emphasis was encouraging units to put together these annual histories. Some are just stunning – they include testimonies of people baptized or reactivated that year, the testimony of a young man who received the priesthood, and his experience administering the sacrament. People come up with creative things. As with previous minutes, the efforts are spotty – they’re not all comprehensive, and they’re certainly not all submitted. But that is one way of keeping this history worldwide. Records like that and individual diaries are what the historians have drawn upon to write the Saints volumes of the 20th century.

What impact has writing about Eliza R. Snow specifically had on you?

I have now lived with this woman for fifty years and I’m still learning new things about her. This is a person of extraordinary intelligence who consecrated her gifts to build the Kingdom. The compilation of her poetry – those five hundred poems – was an important part of my coming to know her better. We have only three diaries – one from Nauvoo and two from the trail – that show us something of her private thoughts. We have a handful of letters and a rich trove of discourses from the last twenty years of her life.

Eliza R. Snow, The Complete Poetry

Consistent across her life were her poems. One of the important concepts that has come to me from looking at her poems is her capacity to work within patterns and structures to express herself. In some ways, this is the story of her leadership: this capacity to be creative and express herself within a form or structure. Within the ecclesiastical structure of the Church, we see her moving forward creatively to make things happen and still maintain allegiance to the structure, just as she could conform her thoughts to some pattern and form of meter and rhyme in her poetry. She’s able to do that organizationally without losing personal integrity or a sense of what she wants to express or advance. That is one of Eliza’s great strengths. I have learned much from seeing her navigate some pretty tight forms and pretty tight places. Not that she never stepped beyond limits – she was reprimanded a few times. But she had an exceptional gift for maximizing possibilities within the organization. This, coupled with her willingness to consecrate and sacrifice, enabled her to make a singular contribution.

She believed heart and soul in the restoration of the priesthood. For her, priesthood order and ordinances provided women and men access to the power of God, and she believed that working within the revealed order was the way she could gain access to godly power, increase in holiness, and assist in the work of salvation, to which she was deeply committed. That is the core of her strength – her faith in and connection to Jesus Christ, her devotion to His Kingdom on earth and to the possibilities of holiness He offers each individual. Her vision of and commitment to the power of priesthood order and ordinances has had a tremendous impact on me.

I’m sure it has. How can we now – both men and women – benefit from studying Church history and the women in particular?

I think we can benefit by the same sense of discovery and fascination that I’ve tried to convey. The more stories we have, the more satisfying it is – whether it’s someone from the 19th century or the 20th century. These lives don’t necessarily solve our problems, but they show us such a range of possibility. I hunger for that. The diversity in our history is truly enriching.

As the Church has moved internationally, and we see even a greater variety of lives, we understand that there are many ways to be a faithful Latter-day Saint. There is power in sacrifice, and we can’t study these lives without seeing the power of the sacrifices people have made.

When we study the whole history, we also see that people have opted out all along the way, essentially saying, “This sacrifice was too great for me. The dissonance was too much for me and I left.” Those are also part of our story. We can see those who dissented weren’t necessarily destroyed – many went on to live productive lives. Those examples are also out there. Still, there is a plentitude of diverse examples of people who made the sacrifice to stay, to remain, to live with conflict and dissonance, to work through disagreements among women and men. Disappointment is as much a part of our history as triumph and unity.

In seeing the full landscape more clearly, we get a better sense of what it means to be a Latter-day Saint and how we can commit ourselves to an institution that is both human and divine. We’re going to be disappointed and offended, we’re going to have to sacrifice. But if we believe in that divine power to which the ordinances of the gospel give us access, we can live with those sacrifices and that dissonance, and we can make a contribution to something we believe is divine and far greater than ourselves.

At A Glance

Name: Jill Mulvay Derr

Age: 73

Location: Holladay, Utah

Marital History: Married

Children: 4 children and 11 grandchildren

Occupation: Historian, retired

Convert to the Church: Baptized at 8 years old

Schools Attended: B. A., University of Utah; M.A.T., Harvard Graduate School of Education

Languages Spoken At Home: English, occasionally French

Favorite Hymn: #113, “Our Savior’s Love”

Interview Produced By: Trina Caudle