Bonnie Ballif-Spanvill has dedicated her professional life to the study of peace and how to bring peace to the lives of women around the world. Both as a professor of psychology at Fordham University in New York City for 30 years and as the director of the Women’s Research Institute at BYU for 16 years, Bonnie has demonstrated the power of one to inspire kindness and love coupled with a fierce fight for women’s freedoms. For more on this remarkable woman’s personal life, watch her participate in the MWP 2010 Salon here.

Take me back to your college and graduate school experience in the 1960s. Did you know studying peace was going to be the trajectory of your career or did you just fall into it?

It evolved, but I was always interested in how to help people maximize their own development, so I was interested in psychology and education. I wasn’t just interested in helping people overcome weaknesses or problems; rather, I was interested in the development of their minds. I was fascinated by the concept of repentance, which comes from the Greek word metanoia. The “meta” part means transformation, like metamorphosis of a butterfly. And the “noia” part means the mind, suggesting that the mind can be transformed from an inferior state to a superior state. I wondered a lot about how this transformation takes place, how human beings have the eternal capacity to grown and ascend. So much of the gospel is about growing and progression.

Those were major ideas in my thinking. I was also very interested in Christ’s teachings and His use of the mustard seed as an analogy for faith. It seemed, as I studied more about what that meant, that His teachings if actually used in our lives, can grow from a tiny seed into an enormous mustard plant which bears fruit and more seeds and brings more lifting and expanding. It seemed to me that our power – our ability to think, our spiritual power – could literally explode if we could catch a glimpse of and use His teachings we’ve been taught.

I don’t think we can comprehend the magnitude of this growth and expansion. I guess it is the process that allows a mere mortal to become a god someday.

I’ve met a lot of people who’ve followed those same interests by going into religious studies, instead of something so practical as psychology and really helping other through the practice of psychology. Did you ever consider going into religious studies and studying these concepts academically rather than as a practioner?

I’ve always believed that the teachings of the gospel couldn’t just be something that are spoken about; they need to be lived and used and internalized. There was a part of me that found just the discussion of these issues a little lacking in actually bearing much fruit in people’s lives. Where the excitement comes for me is when I see people really able to grow and transform themselves. That’s overwhelming. You see it with your children; you work with them and help them catch a glimpse of what they can be. So I was interested in the applied part as much as the theoretical part.

Let’s talk about that focus started being funneled into an interest in women and peace. How did your interest in regeneration and connection lead you specifically to an interest in women and peace?

There were a couple of things. Yehudi Menuhin, the violinists, gave an interview in the New York Times very soon after I went to New York in 1968 and the interviewer asked him, with so many troubles in the world, how did he justify spending so much time in his music. Menuhin responded with something like, “It’s for the very reason that there’s so much ugliness and hatred in the world that I spend so much time on music. I have to counterbalance that with something beautiful and lovely and something that represents the best that I can be.”

While I was teaching there, the women’s movement was very prominent especially in New York and I quickly became aware of the disparity between opportunities that were available for women to grow when compared with men. Education, employment, healthcare… all aspects of our society in the United States, but also internationally. What barriers need to be removed for women to excel? What would it look like in a peaceful world where there was great literature and art, but also people knew how to interact with each other in prosocial ways.

How do you actually make a career in that? What sorts of courses did you teach? Research did you do? How did you practically craft those broad, idealistic goals into a career?

I was a professor at the Graduate School at Fordham University at Lincoln Center for thirty years. This was an amazing opportunity for me because I was surrounded by very bright, capable doctoral students. The way I framed my ideas for a non-Mormon audience was in terms of learning and growing and progressing. I was developing a model to help children excel and love learning. As you know, New York City has many different dimensions and there were plenty of opportunities for these students of mine to take parts of this model I was building and use it to help children and adolescents throughout the city grow and learn. This model evolved and grew throughout the course of my work with my students. Many of my students were international because it’s a Jesuit university and drew the attention of many nuns and priests from around the world who come there to study. I was also able to look at parts of my model and see how it worked in different parts of the world.

I was trying to identify the emotional and affective states along with how the brain functions cognitively in order to determine what conditions were the most beneficial to growing and learning in both schools and corporations and lots of other settings. It was a very rich time to explore a motivational learning model, and that’s where my career really took off since no one else was really interested in my thoughts on eternal progression!

One of the most important experiences I had in New York City didn’t occur in the classroom or even the university campus. One morning, my husband Bob and I woke to total silence. We lived on 57th Street, and that morning there was no honking, no talking people, no sirens… It was total silence. We were stunned. We got up and looked out the window at a city that was absolutely buried in snow. There were no cars on the street, even though the traffic lights kept turning red, green and yellow. The stores were closed. Wall Street was closed, schools were closed. This enormous, powerful city had just stopped. We got up and walked around in Central Park and I caught a little snowflake and I watched it quickly melt on my fingertips. I wondered how such a vulnerable little flake could have such a power over this giant city. Then I realized it wasn’t just one snowflake that had done it but millions and millions of snowflakes together that had brought the city to its knees. From then on, I had a perspective that what I was doing was not significant by itself. But if many people would help each other grow and develop, we could develop a culture of learning and of peace. I began to see that having a culture of peace where people are kind to each other really does accelerate learning. If millions of people would do it, we would reduce violence and free people to grow and develop to their fullest potential! I’d already seen in my collaboration with my students that it took more than my ideas to make a difference; it took their teamwork to make them happen. I realized we need to help everyone engage in this process.

Do you feel that you have a spiritual gift for peace, for bringing calm and bringing unity? Not only your career, but your personal life and your demeanor make those around you feel so assured and loving towards each other. Is that something you’ve identified as a personal gift?

That’s a hard question for me to answer. I think as I have studied it more and tried to apply it more in my life, I have become more peaceful. It may be that I’ve always tried to stay very close to my Father in Heaven, and He has guided me so many times and helped me so much. I certainly don’t believe I chose this path on my own. I think He needed someone to work in this space. Whether or not He gave me a special gift, I don’t know but I do know that He’s opened the way for things to happen that are actually miraculous. Maybe I had some tendencies in that direction that He was able to develop a bit, I don’t know.

Let’s move on to your time at the Women’s Research Institute (WRI), which is the department you ran at BYU for 16 years.

One of the things that excited me about the WRI was that it was a place where I could take my theological understandings established through our latter-day revelation and actually use them as a foundation to study the differences between women and men. We basically had three principles that we worked from at the Institute: One is the idea that gender is eternal and a central characteristic of premortal, mortal and eternal lives. There is an identity that surrounds us being female that is profoundly important. We wanted to know what parts of our being female are eternal, as opposed to the cultural things we grow up and learn to be on this earth. This was one serious question we wrestled with at the Institute. We also believed that increasing the understanding of women would have a significant impact on strengthening both male and female spirits as we try to comprehend ourselves and interact in this existence and prepare to interact to interact in the next existence.

The second principle was that women and men are equal, but from a theological point of view. We argue unequivocally for the development of the full potential of each person, regardless of gender. Central to Christ’s work was the way He interacted with women, even though at that time they were relegated to inferior status in the culture. He recognized their spirits and intellects, He taught them, healed them, raised them from the dead. And after His resurrection, He appeared first to a woman and asked her to give the news to the apostles, even though at that time in Jewish law women were not considered competent as legal witnesses. So the fact that He used a woman as a witness is especially profound.

The third principle that drove us came from statements from President Hinckley when he talked about how women had been put down and denigrated and abused and how the full gamut of opportunities were now available to women.

The institute itself was a community of scholars, much like a university department, and it facilitated faculty collaboration. That kind of collaboration increases the quality of research and teaching. That community that the Institute created involved over 80 affiliates from across the other departments of the campus, and also across universities. We made good connections with other scholars that helped on a national level to understand that the attitude toward women at BYU wasn’t as archaic as many of them had been led to believe. Our connections and influence were felt around the world.

The institute did great things: we met every week, we had discussions and lectures and films and it was all built around Christian responsibility to look after the downtrodden. As long as some women are the last to be fed, the first to be denied healthcare, as long as they are abused in their homes and social barriers keep them from growing and being educated and they’re denied opportunities and exploited for trade, then solutions to these problems must be found. We have to study them and find out what it is that is hindering these women and help alleviate those barriers. That’s what, I believe, what the Research Institute fostered in students and faculty.

The most critical challenge of the 21st century is the need to improve women’s lives and increase their opportunities for growth because they turn around and increase the opportunities for grown and development among their own families. There are so many studies that provide evidence that the same amount of energy and effort and resources given to the men does not result in the improvement of the health or education of the children. But when provided to the women, it does. Supporting women leads directly to peace within our communities.

There were three areas in particular that resulted in significant accomplishments, and these were three things I was personally involved in:

First of all, when I started at the WRI, we wanted to identify what constitutes peace from a feminine perspective. There are many men out there talking about violence and peace, but we couldn’t find women’s definitions or discussions of their experiences with it. To start, we needed to carefully define what it was we were looking for and trying to understand. We did interview women to get definitions of peace and women’s experiences with it, but we finally decided to go to the most articulate women in the world: female poets who’ve written about their experiences with violence and peace. We wanted them from all over the world because we wanted to see the similarities and differences. We literally scoured the works of hundreds of poets. Eventually, we published our findings in a book called A Chorus for Peace. It was a global anthology of poetry by women and it was edited by myself and Marilyn Arnold and Kristen Tracy and was published by the University of Iowa Press.

But the way these female poets saw war and strife, on fronts that were both international and domestic, and then the way they wrote graphically and poignantly about these conflicts and how they tore up their lives was just unbelievable. I don’t think it’s appropriate to repeat the poems here, but for example one woman from Africa talked about her memories of violence being like broken glass running over smooth skin. With just that image you begin to get a female perspective. Many of them were about rape and devastating birth circumstances and other heartrending situations. But, out of these ashes of violence, these women insist that peace be born. They want peace, and they describe peace and they plead for peace. One woman from China starts her poem with, “Let me be in my mother’s arms. Let my mother be in a small boat. Let the small boat be on a moonlit sea…” You begin to get this sense of peace that she would feel in the arms of her mother. It was an amazing collection of feminine perspectives.

I’ll never forget the poem you read at my baby shower by the Chilean poet…

Was it Gabrielle Mistral? Actually, that one about rocking a baby was in this collection. What’s so interesting is that women have similar feelings and perspectives. We relate immediately to rocking a baby or being rocked in a boat by a mother. We react to the image of broken glass on smooth skin. There is something that is eternal about being female that, I think, is universal. There are, of course, many modifications of what we start with, but at least in these poems we read and studied there was a great deal of blending of voices in a heartbreaking plea for peace.

The second series of studies I worked on was with Valerie Hudson, Mary Caprioli and Chad Emmett and these were studies that were just published in Sex and World Peace by Columbia University Press. There were several elements of these studies that were important. One is that we build an enormous database called WomenStats, which is on the Internet and is free. It’s information about women from all over the world and all aspects of their lives. It’s about the laws of their lands and how they’re enforced in regards to women, their attitudes and mores as well as facts, such as percent of women who die in childbirth. That is a huge contribution, which is already being used by many scholars.

Using those data, we were able to find an empirical link between the security of women and the security of the state. Basically, that means that a country’s peacefulness is not its level of wealth, democracy or ethnoreligious identity, but how well its women are treated. Those studies also show that the larger the gender gap between the treatment of men and women in a society, the more likely a country is to be involved in intrastate and interstate conflict and to be the first to resort to force and higher levels of violence to solve conflicts.

The third area we focused on at the WRI was reducing violence in the home, particularly spouse abuse. The intergenerational cycle of domestic violence is really strong: if there’s abuse in the home, particularly the young sons are likely to be abusively in their own relationships in the future. So we decided to study children who have been exposed to violence in the home and compare them with children in nonviolent homes. We saw what the differences were in their patterns of thought and their emotions so that we would know how to address those who have been exposed to the violence and how to stop it in the future. We found very specific thoughts and emotions in witnesses of violence that are different from those of other children. We also identified, from the different types of conflict that are common to children, the one that is most likely to erupt into violent episodes: that is feeling excluded, not being allowed to play with someone, or being left out of some sort of gathering.

We developed a program from these findings which we believe can provide an intervention for these emotions. It’s called PEACEABILITIES, published by Brigham Young University.. It’s an intervention program that increases children’s abilities to be peaceful in all kinds of interpersonal relationships. It’s just barely come out and it’s a collection of compelling stories and songs and games and artwork and activities that originate from many ancient and modern cultures. It’s unique in that it develops the internal strengths that children need, rather than external controls. If I have a brain tumor, I don’t want a surgeon to go in near where the tumor is. I want the surgeon to root out that exact tumor. It’s that sort of precision we believe PEACEABILITIES has to target the root of the behavior. It’s not going to solve all world conflict today or tomorrow. But if it can be used as a model for selecting specific resources that target specific behaviors, then maybe children will be less likely in the future to be angry and escalate their own feelings into conflict. There will be less spouse abuse and neighborhood fighting. There will be less tribal fighting… That, I know, is a dream, because we’re a long way from having materials in all the languages we need. But the vice president of the Democratic Republic of the Congo is really interested in PEACEABILITIES and wants to get it translated into French… There are many opportunities to spread this program..

We are trying now to raise money to place it in shelters for domestic violence families, schools and non profits. Since we’ve started this, we are beginning to see women who are determined to develop children’s abilities to be peaceful joining together in what is being called now the PEACEABILITIES movement in order to break violent patterns. This is exciting. Here’s a real key: peace is not the absence of violence. That’s just parallel living. Peace is not something warm and fuzzy and lovey and dovey. It’s very specific skills you have to interact with other people. And they can be taught.

I read a good portion of Sex and World Peace, but I didn’t finish it cause it is heavy stuff. All of your work deals with heartbreaking circumstances. In the face of all of this devastating information, both statistically and anecdotally, that you have worked with over the course of your career, how do you stay positive and optimistic about the future of women?

There’s nowhere else to go. We have to go up. We have to get better. We have to make a way for things to improve. Again, it’s not just one person. All of us have to work together. President Hinckley famously implored us to be a little kinder, be a little more considerate, be a little more gentle. That’s the only way to go. I don’t want to contribute to the negative things. I guess that’s where the mustard seed comes back to me. I still believe that if we will try just a little bit, peace will grow. You just have to have hope and keep trying. I don’t have a magic ball. I don’t know if we are going to destroy ourselves as human beings; there are certainly some pessimistic prophecies ahead of us. But among those prophecies and that pessimism, is always the constant promise that hope and charity and faith will keep us going. Those three things, in a very applied way, keep me going.

I think when I started out as a graduate student, I had no idea what was going on around the world for women. I did not know. But as I tried to study and figure out how to remove barriers, I considered only very little barriers until I was actually truly studying world issues. Then it seemed overwhelming. But you just have to pick up your feet and take one step and then another and another… Hopefully, it’ll make a difference, if not to many then to one or two.

I find it fascinating that the greatest advocates for women’s equality in the academic world come from Mormon women like you and Valerie Hudson. What do you say to a critic who wonders how this emancipation of women globally can be led by Mormon women?

It is our theology that gives root to the ability to keep going. My passion is a natural outgrowth of our doctrinal beliefs. One of the things that concerns me most is we are not teaching our young people the theology. We’re teaching them behaviors: do this, don’t do that. But we’re not teaching them things like the forever existing intelligences which we all are, and the whole concepts of our eternal identities, especially our identities as females. That concept gives me great energy to try to figure out what that means and to try to encourage females to be females! I think a lot of females have sold out, frankly, and try to live in a male world according to male norms. But I don’t think we know what it means to be a female from a spiritual perspective that is eons old; I think we’re so culturally bound. I’m on a detective mission. I’m on an intense search to try to figure that out for myself… and for my daughters!

I believe in the contagion theory. We’re all worried about one flu or another spreading the world and wiping us out. My vision is, Let’s spread these ideas! They do catch on with some, and we can remove the violence against women and the barriers in developing their creativity and voices. I think that is the last phase of the development of the earth. We have a responsibility to do it.

The last chapter or two in Sex in World Peace talk about specific things that can be done and individual women who’ve stood up and done things in their own countries. There’s a movement in India, for example, for the women not to marry the pursuing male if he doesn’t have a toilet in the home. They’re standing up for having things that make their lives better and more manageable. We’ve moved away from the collective forum of formal violence like world wars. We don’t do that anymore. But we have so much informal, personal, neighbor-against-neighbor, intimate, family, bullying in schoolyards violence. These things can be fought at a personal level if we give our children the tools to teach them. That is the major challenge of the 21st century: to stop violence. Violence begins in the mind, long before weapons are fired or abuse is afflicted. So preventing violence also has to take place in the mind.

Just as women are in the most vulnerable position during wars, they are also in a key position to lead this challenge against violence. They are with their little children before those children are socialized to hate. And if they could get started teaching peace, not just one woman with one child, but dozens of women with dozens of children, and hundreds of women and millions of women… I get a little emotional. We’ve got to figure out a way to fill the world with these abilities. Women have got to believe they can change the young hearts around them, and that if they do so, the momentum will build and peace will ripple through homes and neighborhoods and even countries. Peace will triumph, quietly and tenderly.

At A Glance

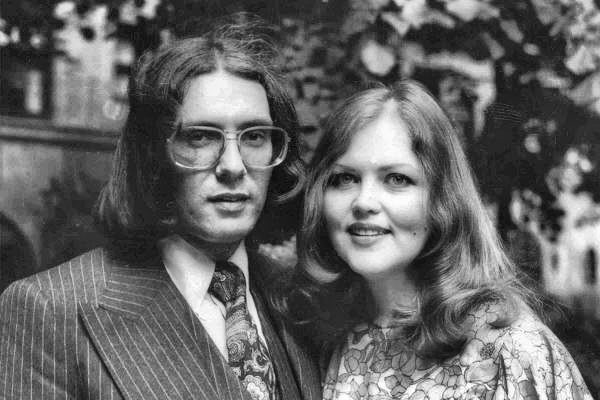

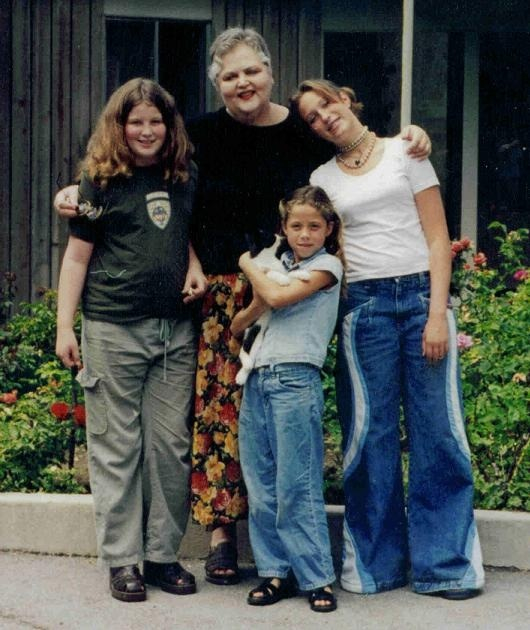

Bonnie Ballif-Spanvill

Location: Provo, UT

Location: Provo, UT

Age: 72

Marital status: Widowed

Children: 3 girls ages 28, 25, 23

Occupation: Research Psychologist, Writer

Convert: Baptized at age 8, converted gradually until I had sure knowledge at age 18

Interview by Neylan McBaine. Photos used with permission.

At A Glance