Because readers of the Book of Mormon today often wrestle to make sense of its portrayal of women, an otherwise obscure figure from the Book of Alma has in recent years become an oft-celebrated heroine. Mormon recounts the story of Abish in Alma 19, and we’d do well to slow down and sift this particular scriptural text whenever we come to it. In fact, we’d do well to return to the story often, since there Mormon gives us one of the very few glimpses into the gender culture of the Lamanites—which, as the prophet Jacob tells us from early in the Book of Mormon, looks quite different from the dominant Nephite gender culture we spend most of our time reading about.

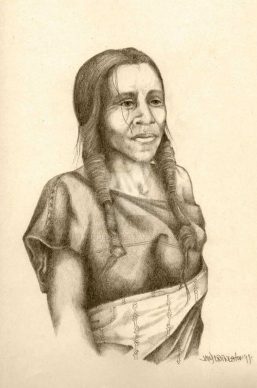

Abish by Jody Livingston

As one of only a few Book of Mormon women whose stories are told in enough detail to provide us with a real sense of their contribution, Abish deserves to be called a foremother for faithful Latter-day Saints today. Abish is in fact a remarkable example of what we’d today call intersectionality. That is, she finds herself without social privilege in three ways at once. First, as a Lamanite, she was or certainly would have been treated as a racial other by the light-skinned Nephites who stand at the center of the Book of Mormon’s larger story. Second, as a woman, she finds herself without certain social and cultural opportunities enjoyed by her brothers. And finally, as a servant, she was located at the bottom of a steep economic ladder, lacking rights and privileges others had.

Abish’s social circumstances echo a passage early in the Book of Mormon, where the prophet Nephi says that God denies none who come to him, “black and white, bond and free, male and female.” On all three of those measures, Abish could count on those around her denying her access to things and opportunities. In fact, the way Mormon tells Abish’s story, it seems he deliberately highlights her triple disadvantage. The story focuses first on the Nephite missionary Ammon, a figure of privilege in all three ways: he’s a Nephite, a man, and a prince. But then it comes to focus on Lamoni, the Lamanite king. Lamoni lacks one form of privilege since he’s a Lamanite, but he shares with Ammon the other two forms of privilege, in terms of gender and class. As Lamoni falls into a converting swoon, however, the story shifts its focus again, now to Lamoni’s wife. This queen lacks two forms of privilege Ammon enjoys—she’s not only a Lamanite, she’s also a woman—but she shares at least one form of privilege with him, since she’s at the top of the economic hierarchy. Finally, though, as the queen too falls into a spiritual trance, the story comes to focus at last on Abish, who lacks privilege in all three regards.

Mormon thus moves his readers through the story, tracking with them how each succeeding focal figure is less and less privileged but nonetheless stands at the center of God’s work in converting the Lamanites. This progress comes to its culmination with Abish, who essentially has nothing going for her. But, although she could count on human beings to treat her as less valuable because of her sex, her race, and her class, she didn’t hesitate to trust that God would use her. She seized the opportunity to set something crucial in motion, and it turned out that God had prepared her for exactly the moment she was willing to improve on. Abish marks the turning point in the history of the Lamanites. After five centuries of privileged Nephite men going among them hoping for missionary successes, it turns out that it’s this poor woman of color who stands at the fulcrum and initiates what is still the work of fulfilling God’s covenant promises to a misunderstood people.

Abish leaves us with work to do. She shows us that God sometimes has to push everyone with privilege out of the way so that he can call on those despised by the world to do the most crucial work. And she doesn’t hesitate to affirm God’s universal love despite social barriers, demonstrating to everyone that God means what he says through his prophets about real equality. Abish is a Book of Mormon figure for the twenty-first century. We struggle to achieve the ideal, and too often we resist making the changes God calls us to make so as to see that ideal realized. But Abish was ready and willing, divinely brought to the right place at the right time to begin to see God’s grandest promises fulfilled. Heaven help us to be so ready and so willing—and, where our own privileges obstruct the work, heaven help us to let God gently move us out of the way so that he can do his work.

(Guest writer) Joseph M. Spencer is a philosopher and an assistant professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University. He has degrees from Brigham Young University, San Jose State University, and the University of New Mexico, having earned his PhD in philosophy from the last institution in 2015. He is the author of four books (most recently 1st Nephi: A Brief Theological Introduction), the coeditor of four collections of essays, and the author or coauthor more than fifty articles and book chapters. His work focuses on philosophy, theology, and scripture.