A popular professor at Brigham Young University, Susan Easton Black was the first female full-time professor in the school’s religion department. When Susan become a single mother to three sons, she was forced to evaluate how best to provide for her young family. In her academic pursuits, Susan rediscovered her childhood love of church history stories and has crafted a vibrant career for herself which includes her most recent publication, Women of Character, a book profiling a hundred well-known LDS women through our history.

You were the first female full-time religion professor at BYU. Would you describe how you got to that position?

I grew up in Long Beach, CA and my grandmother lived with us. And she would tell me stories about various pioneers and Joseph Smith and family members who had crossed the plains. My interest in Church history started with that. Then I attended Brigham Young University and I took classes from a man named Milton V. Backman Jr. He told me the same stories my grandmother told but he knew how to document them. It was very exciting for me to listen to this professor, especially after my grandma had died. I went from the back rows of his classroom to the front rows. I convinced my parents to let me go on a Church history tour that Prof. Backman led one summer, and after I had seen Nauvoo I was completely enamored with everything about Church history.

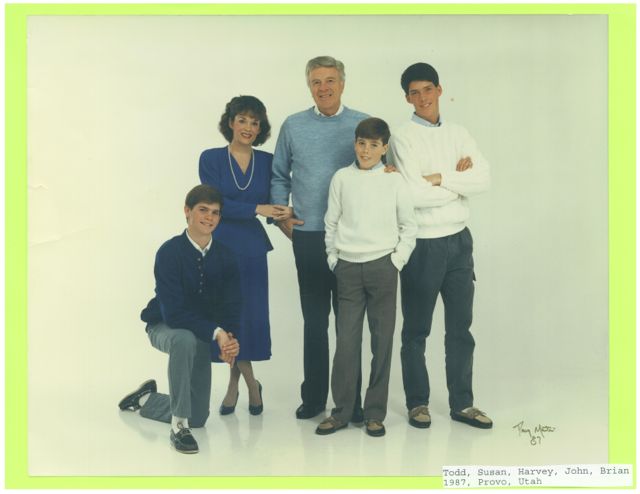

I graduated from BYU, married, and then had my family, but kept a friendship with Milt Backman.

Did you know this would be a professional pursuit when you graduated from BYU? It doesn’t sound like you anticipated going back to school after you started your family.

Like most of the women of my era, I anticipated that I would graduate and marry and have a family and that that would be my life. I had seen Church history as more like a hobby: something I’d continue to be interested in but not as a career.

I had three children but then I went through a divorce, and I had to figure out how to support myself and my children. I concluded I’d go back to school. I was living in California at the time and although I had a bachelor’s degree from BYU, I discovered that if I wanted to teach there I needed more than a provisional certificate. I would need another two years of schooling to be hired by a California school district. I could get a master’s degree in one year, and then I could teach at a junior college, which would mean less time away from my children, who were four, three, and one at this time. So I concluded that going back to school to get a master’s was the quickest thing I could do.

I had done my undergraduate work in political science and history and my master’s was in counseling. I thought I would end up at some junior college or at a high school as a counselor. When I finished my master’s degree, I got a job at a junior college in San Bernadino. I taught Psychology of Women and Psychology of the Individual. Nothing through all of that suggested I’d end up doing Church history. But interestingly, at the same time, I had a great interest in the scriptures–I was the gospel doctrine teacher in my local ward, and I enjoyed teaching as much there as I did in the professional teaching arena.

During this time as a single mother, did you feel supported in your endeavors to provide for your family?

I always felt supported by my family. A visiting teacher in my ward watched my children one day a week while I was in school. I could pay state tuition but not state tuition and babysitting, so she made it possible for me to go to school and I will be forever grateful to her.

In my master’s program, I discovered that I was doing well in school. I hadn’t felt like a particularly strong student as an undergraduate. But now I had a different attitude and I had a goal in mind: I felt that if I pursued a doctorate degree I could help my family have a house, a car, a real middle-class life. And at the same time, as a professor, I could spend fewer hours in the classroom–fewer than I would in the public school system–and I could write. I could write anywhere, even at home, so I felt that would enable me to still be a mother in the home as opposed to spending hours away from my family. That was the impetus. I got my doctorate in educational psychology with a minor in Church history at BYU.

While I was working on my doctorate, I taught Book of Mormon and Church history classes part time, but before I had even finished my degree I was hired to be part of what was called the College of Family Living at BYU. I taught about such things as the psychology of consumerism and financial portfolio analysis.

Were there other women you could look up to at that time?

There weren’t a lot of women who were professors or had doctorates. I was only in that department for a few years – from 1978 to 1981 – but those years corresponded with the push for the Equal Rights Amendment in the United States. At that time the president of BYU was Dallin H. Oaks, who was raised by a single mother, much like my own sons. He began looking through the University to make sure there were female faculty members in each college. He discovered through that process that the Religion Department had not had a female full-time faculty member since the beginning of the University – 107 years! By this time, I was an ad hoc professor. I was teaching in my own field but also teaching about three religion classes at any one time. I was publishing in Church history and Book of Mormon, and so I was invited to transfer out of Family Living into a full-time position in the Religion Department. I’ll be forever grateful to Elder Oaks.

To some extent, it was a difficult decision because I realized I’d go from opportunities to speak at professional organizations and conferences around the country to doing firesides and “Happy Birthday Relief Society” talks. So it has been! For example, I have a son who is a professor who asked me recently if I’d spoken in Washington D.C. I assured him I’d spoken at visitors’ centers, at the Washington D.C. Visitor’s Center, at mission conferences, firesides… Well, he was about to speak at the Pentagon! So the differences professionally are there, but so are the blessings that have come from making that choice. I don’t think I would have had the highlighted career I’ve had if I had stayed in psychology. The decision appears to have been right.

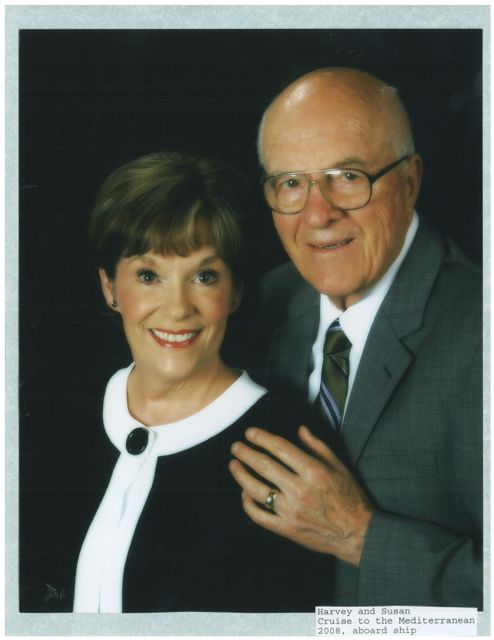

Would you tell me about your second husband?

My husband is now deceased. He died this past summer. I was a single parent for thirteen years. I had finished all my schooling and gotten well into my 40s as a single mother. When I remarried, my oldest was seventeen and I had been raising him alone since he was three. My husband and I were married for 25 years.

You recently published a book of profiles of LDS women, Women of Character. What perspective have you gained on women in the Church since you’ve taught Church history and worked on this book?

Our women go through different phases. For example, in Nauvoo only a few of the women were journal writers and there were many who fulfilled traditional roles. But once you get women crossing the plains and especially during the efforts to get the right to vote in Utah, women had opportunities to go East to get degrees and you see women being very vocal in the Church. Then you fast forward to today and you see women being cheered for stepping out and making a wonderful difference in their communities. We’re more featured than we have been in years past. In years past, we had a handful of women, like Eliza R. Snow and Emmeline B. Wells, who were public figures, but that was mostly associated with their high callings in the Church. But now our women around the world have a voice, whether it’s through a blog or politics or something featured in Mormon Times… I see a willingness to embrace women who are saying, “I can do the traditional roles and reach out with something to benefit my community.”

Readers may already know some of the women profiled in Women of Character, but by putting them together in one book, my co-author and I are giving readers a wonderful perspective on what women throughout our history have done for the Church. That involvement builds in momentum until you get to today, with modern women who are making a difference all over the world.

Would you share one or two stories that meant a lot to you as you researched the book?

I had an opportunity to speak at the Winter Quarters’ Visitors’ Center several years ago about the pioneers. Metropolitan Opera soloist Ariel Bybee had also been asked to be on the program with me. She was to sing “Come, Come Ye Saints,” a hymn that is so closely associated with our own heritage. How many times had I heard that hymn? But this time I actually saw the professional singer perform it. It was such a physical performance; you would have thought she was on the opera stage in front of thousands of people. There was so much energy and power in her performance. At the end, sweat was just pouring down her face like she had given it her all. I remember saying to myself, “I always want to be a teacher like that; I don’t ever want to go into a classroom saying I’m just winging it today or I don’t know much about this topic so don’t worry about taking notes.” I wanted to magnify the talent I had in the same way she magnified hers. It was the first time I’d seen someone who really put “might, mind, and strength” into what she did. It didn’t matter that we were in the basement of a visitors’ center with barely a hundred people present. It was phenomenal.

Another woman who had a big impact on me was named Ettie Lee. She never married. She had a strong interest in young men and was concerned that so many were dropping out of the Los Angeles school system. She felt the reason was that they didn’t have a lot of support or guidance at home. She tried to get grants and government support and philanthropy to help with these young men but she was having no luck. So she decided that if no one would support her work financially, she would. At the time, she was making $200 a month teaching junior high. She decided she’d take $100 of that each month and invest in real estate. It turned out she was really good at it and by the time she got close to her death she had purchased ten homes where young men could live and be mentored. She took 300 boys off the streets of Los Angeles each year and gave them an opportunity to live in those homes. She reached beyond her circumstances and helped so many others through the years. She made a marvelous difference.

If you were to write this book in fifty or one hundred years, how do you think profiles of LDS women would change in the future?

If I were to write a similar book, it would be even more difficult to narrow the field than it was for this one! But the ethnic backgrounds of the women would be much more diverse, much more international. The Church is moving forward and as it becomes established in so many countries, we’d still find women who have honed their talents and become exceptionally good at what they do, but the faces of the women would look dramatically different. There would be an international look to their profiles.

Is there anything else you’d like to share in closing?

For me, the message that I’ve learned in my life is that it isn’t what happens to the woman, it’s what she does with what happens. If women learn what their strengths are, and if they stick with those strengths, their lives seem to be happy. If you keep the commandments, there’s a sense of peace but there’s also a sense of confidence that you can do what you set your mind to regardless of the obstacles. I express a sense of gratitude that during the ups and downs, the good, bad, and ugly, we can know there’s a Father in Heaven who’s pulling for us, even when there are others who are claiming we can’t do things. Doors do open. You have a chance to be who you’re meant to be. I’m forever grateful for those who opened doors on my behalf and gave me a chance to teach the subjects I love.

Interview by Neylan McBaine. Photos used with permission.

At A Glance