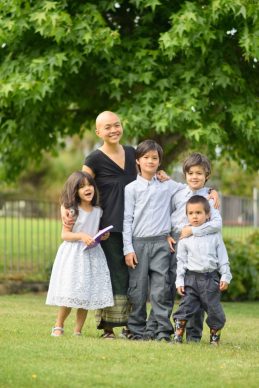

Melissa Wei-Tsing Inouye grew up in the Church. She earned her BA and her Ph.D. from Harvard University and now teaches history at University of Auckland in New Zealand. She and her husband, Joseph, are the parents of four children.

You have a long family history in the Church. Can you outline it for me?

My grandparents on both my Chinese side and my Japanese side joined the Church.

My Chinese grandmother, Marjorie Ju Lew, grew up in Salt Lake City, where her father Gin Gor Ju was known as the Celery King and was famous for selling celery. He had immigrated from Guangdong Province in China. She claims that he was the person who pioneered the practice of using rubber bands to tie produce together. That’s hard to verify! But he was a farmer in Utah. They had Mormon neighbors, in particular a family that lived near them called the Sorensens. The two families had a symbiotic relationship. They were good friends and they helped each other in various ways. My great-grandfather, Gin Gor Ju, hired the sons to work on his farm, and this is how they paid for their LDS missions. The Ju family kept a cow, which the Sorensen kids milked. The Ju family kept the milk, and the Sorensens kept the cream. When my great-grandmother, Gor Shee Ju, lost a child, the Sorensens told her that there was a way for her to be reunited with that little boy eternally. That was when they joined the Church.

My father’s side, the Japanese side, also came to Utah, but in a different way. They were “interned,” imprisoned rather, in the camps for Japanese Americans during World War II. They originally lived on the West coast in California and Washington State. There they had homes and farms. My grandmother and grandfather were native-born Americans who spoke English as their first language. In 1942, anti-Japanese sentiment spread throughout the United States. Roosevelt issued an executive order that all “persons of Japanese ancestry” were to be transported to camps in the middle of nowhere and locked up behind barbed wire. My grandmother and grandfather met and married in the camp at Heart Mountain, Wyoming. As the war drew to an end, they were given about twenty dollars and told to go and make a new life for themselves. So they ended up in Sanpete County, Utah, and that’s where Bessie Shizuko Murakami Inouye and Charles Ichiro Inouye encountered the Mormons.

My father was from Utah but he eventually moved to California. So I grew up in California. I spent most of my life in the city of Costa Mesa in the Costa Mesa First Ward.

You’ve written eloquently about being a teenager, doing everything that was expected of you but still struggling with your beliefs. What’s an experience that captures that tension of wanting to do what was right but then wondering if that in itself was right?

I have one memory that crystallized the problem in my mind. When I was a high school student I faithfully attended seminary and Sunday School. But one day my Sunday School teacher ridiculed the idea that the theory of evolution was correct. He said, “This is ridiculous. You think we came from monkeys?”

I thought, “Well, I don’t know!”

So I went to the counselor in my bishopric and he gave me a book that had been written by Joseph Fielding Smith, Doctrines of Salvation. In that book it says it’s impossible to believe both in Jesus Christ and in the theory of evolution.

And so I said, “OK, I guess that’s the position.” But I was still unsettled by it. My understanding of truth is that it’s like a line that you can continue to extend along a vector. If the line can be infinitely extended it’s true. But all of a sudden I felt like there were lines of scientific truth and religious truth, both pointing in different directions.

At the same time I was being interviewed at BYU for the Hinckley Scholarship, which was a scholarship that was given to people who were getting high grades in math and science, among other things. So here I’d been invited to visit BYU because I had been getting high grades in science, in which the theory of evolution plays a very important role. And yet it was supposedly not ok to believe in the theory of evolution and in Jesus Christ at the same time!

One night, when we were all hanging out, I asked the other girls interviewing for the scholarship–really smart girls—what they thought about the theory of evolution. They said, “Well, it seems like scientifically it’s a valid theory and it explains a lot of things.”

And then I pulled out my Joseph Fielding Smith and said, “Look at this book!” Here was a Church president saying it’s impossible to believe in Jesus Christ and believe in evolution at the same time. Everyone was stymied. Nobody knew what to say. We didn’t know what to think.

Later on during this same visit, I met with Bill Bradshaw, a biologist. So I asked him this question and he said, “Oh, evolution is beautiful! Evolution is wonderful! And Latter-day Saints frequently misunderstand it.” Then he produced for me an essay which he has since published, explaining the compatibility of the theory of evolution and Latter-day Saint theology.

That was my earliest memory of feeling that my current understanding left me with a contradiction that I couldn’t immediately resolve. I had to wrestle with it, to go beyond my comfort zone and seek guidance. It took a thoughtful scholar who had mastered both the science and who had been a Latter-day Saint for a long time to help me understand how these two apparently clashing lines of scientific and religious truth related to each other and actually pointed in the same direction.

A few years after this experience you served a mission. How did you decide to go on a mission?

I’d always wanted to go on a mission. I just wasn’t sure I would be able to look people in the eye and say that certain Standard Missionary Propositions X, Y, and Z were true. As a high school student or as a college student I certainly felt that those things were true but that’s different from telling somebody else to believe that whatever you’re saying is true, to change their lives and rearrange their world views. It seems irresponsible to go on a mission and spread that kind of message if you’re not completely sure.

So I finally went on a mission when I felt like I could take those positions. To get to this point, I leaned very hard on a friend of mine, also an undergraduate at Harvard, who left on a mission to Brazil after our freshman year. I corresponded with him on his mission about his experiences and reflected on what he was learning. Over the course of this dialogue, I finally decided that I could say what I needed to say as a missionary. I went on a mission to Taiwan after my junior year of college and then went back to Harvard for my senior year.

It’s wonderful that another missionary’s conversation is part of what led you to the decision to serve.

I think that’s part of how the church works. It’s through being thrown together all the time, living our lives together, that we develop relationships of trust. Through those relationships, we can live vicariously through other people. We are put into contact with the things they are experiencing. It’s this massive experience-consecration, in which someone’s experience, because of your closeness with them, becomes part of your own understanding. When they share their experience with you, or when you observe how they meet challenges and make choices, it’s not quite the same as having the experience yourself, but their insights, feelings, and righteousness all come to you in different ways. I think that’s what Mormonism does. It creates these communities of people who have had really different experiences and perspectives, and forces them to work together and love each other. That’s what I’ve found everywhere I’ve gone, from Spanish Fork all the way to New Zealand.

What are some of the best ways you’ve seen that we consecrate or share experiences?

This may seem kind of cliché, but I feel that sharing comes through our lessons—Relief Society lessons, college family home evening lessons. We’re teaching each other all the time. It’s a great format to exchange experiences and to supplement what you hear with your own experience. Our lay congregation structure is really conducive to that kind of exchange.

You are now a scholar. What path brought you here?

I’m a historian. I study Christianity in China. I started working in this particular field as an undergraduate at Harvard. I had to write a paper using primary sources and I discovered in the Harvard Library the unpublished manuscript papers of an American Methodist missionary who went to China in the late 1800s. I thought his papers were very interesting. Obviously as Mormons we’re very interested in missionaries, and I was amazed at the kinds of linguistic and cultural dilemmas this man was encountering. I watched him trying to figure out how to translate ideas that he had originally assumed were universal, easy-for-everyone-to-understand kinds of ideas, but which he then realized seemed absurd and ridiculous in a Chinese context. They simply did not make sense in this new context and he had to retool his assumptions about everything. I was fascinated by his particular struggles with language and with culture and with the bigger puzzle of the cultural worlds that shape people’s deepest beliefs. That assignment led into my senior thesis project which led into my proposal for graduate school.

Then in graduate school I was really lucky to have someone come to Harvard who had been writing a book on Christianity in China, Henrietta Harrison. I started working on heterodox Christian movements.

What does heterodox mean?

Heterodox means the opposite of orthodox. So orthodox is “correct” belief and heterodox means “incorrect,” or more accurately, different or divergent belief.

As a graduate student I began to learn more about the history of a church, the True Jesus Church, founded in 1917 in Beijing. Like our church, they believe that they are the one true church of Christ on the earth. I thought it was very compelling that the True Jesus Church has been seen by some as a cult or as a heterodox religion because I come from a religion that is also seen as a cult or a heterodox religion. So I was very willing to suspend judgment and investigate the True Jesus Church’s history, beliefs, and practices. There are actually many very compelling parallels between the True Jesus Church and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints! So that’s the world I live in today: global Christianity, religious history, new religious movements.

Tell me about the logistics of living in that world with a family. I understand you and your husband have taken turns being the primary breadwinner and also being the trailing spouse.

When I went to grad school my husband followed me to Boston and found a job at a middle school, so now he has all these great stories from being a middle school math teacher in Malden, Massachusetts. And then I followed him to law school in Los Angeles at UCLA. While there I did my general exam preparation out of residence. And then when I did my PhD research in China he deferred his job with a corporate law firm for a year and was a stay-at-home parent with the kids.

Then we went back the other way. In 2011 we moved to Hong Kong. By this point I had my Ph.D. and three children—it became four in 2012—so I was busy picking kids up from school and going to cello lessons and shopping and stuff like that. I had a regular part-time babysitter, which gave me a couple of hours each day to work in the archives at Hong Kong Baptist University. When I had a tiny baby, I took him with me to the archives and he just slept. I also taught a class at Hong Kong University on the history of religion in America, which was very fun.

My husband was a lawyer in Hong Kong, which is basically the worst place in the world to be a lawyer. It was so terrible. If he came home early he got home at 10:30 PM. Normally it was more like midnight. Late was later than that. It was just not very sustainable in terms of having a good, balanced family life, so I decided to go on the job market. I got a job offer from University of Auckland. I wasn’t really serious about taking the job, but my husband, from his desk in his law office would daydream about this other fantasy life and google “New Zealand.” One day he came home and said, “They have glow worms in New Zealand. Let’s go see the glow worms!”

So I said, “OK. Let’s go see the glow worms!” That was what brought us here. He was home with the kids for about a year and a half while we were figuring out our life in New Zealand and now he works at a law firm. He takes the kids to school and I pick them up. We have four kids; they are 10, 8, 6, 4. Three boys, and one girl.

It’s an interesting career path!

I’ve had other friends who have taken the same meandering route into academia. I think it’s common with many women academics. They don’t go full force for a while because the time when you’re usually establishing your career happens to correspond with the time people are establishing their families, and women often disproportionately bear that burden.

Before going to grad school I talked to Laurel Thatcher Ulrich and she said, “I had my family and then when my kids were basically grown up, I had my career.” So I felt like if Laurel could do that and still have the amazing academic career that she’s had, then it’s almost like a bonus, to be doing research now, and I’m really grateful for the opportunity.

You and your husband have managed the transitions in your career paths by not necessarily staying tied to traditional roles. But I’ve read that before you married, while you very much wanted to marry your husband in the temple, you were intellectually uneasy with issues of patriarchy. Can you talk about that tension?

It’s very interesting, right? Because the temple liturgy itself is very patriarchal, especially the marriage liturgy. It puts man in the position of God and the words and actions of God into the husband’s mouth and hands. So as I thought about getting married and going through that ritual it was ironic to me because I was an ordinance worker in the Boston temple at that time, with a thorough mastery of the entire temple liturgy. And yet my husband, by virtue of being male, was going to be the one speaking those words authoritatively, guided from the side by a male ordinance worker. I thought: I’m the one who knows the temple ceremonies and who guides people through the temple ordinances, and yet because he’s a man my husband is going to be the one who “instructs me,” and I’m just supposed to respond to what he says?

Maybe that was a prideful attitude. But it made me think about the patriarchal order of the Church and about who we put in positions of power to speak powerful words. In this case I realized it wasn’t going to be me speaking powerful words, simply because I was a woman. That’s kind of difficult. On top of that, I had to ask myself, why is the liturgy structured this way? What meanings do these words convey? So I had to ask myself, what are these words trying to tell me? Is Joseph, my husband, supposed to be God to me? Am I supposed to worship him? Do whatever he says? These propositions didn’t sound like the foundation for a happy partnership.

At the same time, I knew Joseph was a wonderful person. He was supportive of my plans to get a Ph.D., and I felt like he embraced everything that I was. I felt like he’d gotten that way because of his parents and his parents’ teachings, and because of his deep beliefs that he’d gotten through his lifelong training in the church.

So, liturgically, I was being told to submit to a lower position within a patriarchal hierarchy, but functionally I was getting this awesome, egalitarian husband who loved and respected me, which is what you want in a husband! I thought it would be wonderful to be married to him for a really long time.

So in this case, you have the patriarchal system on the one hand and then you have the living breathing human being on the other hand. The more substantial thing, the more immediate, persistent reality in my life is the human being, the person with whom you live and share your cares and raise a family. And I was in love with Joseph because he was so wonderful and smart and funny and so on. So I thought, that’s still a really good deal.

I had also seen historically how even the temple liturgy has changed considerably over time. So I thought that maybe the troubling aspects of patriarchy within Mormon religious structures was not a deal-breaker because it was probably subject to future transformation.

Have you found that experience has made a difference when people come to you for counsel who are struggling with their church membership? Does that inform how you talk to friends?

I think in some ways we’re only good at counseling other people if we’ve actually experienced these or similar challenges ourselves. So I’m a very terrible mentor to people who have been, for example, sexually abused by male Church leaders, or who have been physically abused by their Mormon temple marriage husbands, and so on. I have not had those experiences myself, although I try to do what I can to foster a safe and supportive culture at church.

Where I do feel I’m able to offer some counsel is with problems stemming from history, doctrine, liturgy—information, narratives, perspectives, the stuff in books, the stuff you make flowcharts out of. I feel that in my experience I really have found that the competing narratives that we think about, argue about, and worry about are not the core of Mormonism. The core of the faith as I understand it is our relationships with each other and the communities we build, and the relationships we collectively establish with each other and with God.

Tell me about your family’s participation in your ward community.

Our ward right now is quite small. I play the piano in Primary and my husband is the elders quorum president. He’s working really hard to revitalize the elders quorum and to get people to come into church.

I really love going to church. All the times I’ve experienced church in a small unit it’s lots of fun. It’s a lot of work because you have to be involved but you get to know people and the kind of individual personalities of the people in the ward influence the culture of the ward noticeably, more than it would in a larger kind of institutional ward. It’s how I feel Mormonism works best organically.

Are there other things you’d like to talk about?

I wish that we as a Church would get a little better about talking about women. I feel that for various historical reasons this has become a sensitive subject for us. Which is in some ways silly because half of us are women.

What would you hope for when it comes to talking about women?

Especially in America, but also in places like Hong Kong and New Zealand, society has become partisan or polarized to the extent that if you express an opinion, that opinion immediately gets associated with a whole gaggle of ideas that’s quite complex and all-encompassing, though the scope of what you intended was much narrower. That partisanship can lead us to discount or ignore the positions or perspectives of women whom we perceive to be on the other side of whatever it is.

You’re not talking about political partisanship but idea camps.

Political partisanship is part of it but it’s not everything. It’s not Democrat and Republican. There are camps of women. I feel like we spend a lot of time showing how one camp is right and the other is wrong when that’s counter-productive.

Are there ways you’ve found to try to change that dialogue?

Well, I deliberately am cautious of affiliating with groups that have large platforms for that very reason. I’m the kind of person who doesn’t like to buy a set of knives. I’m Japanese, so in my kitchen I have many different kinds of sharp knives. It seems silly to me to think that some company could sell you a set and every single knife would be exactly the best kind of knife for every kind of job.

My point is that I’m frustrated with parties, institutions, and organizations in general. Which is ironic because I love organization! I believe people can do a lot better in groups than they can separately. That’s one of the great things about the Church. It’s like an organization machine.

Organization can be great, but partisanship is problematic. In the worst cases, it creates tribes of people who are invested in either seeing other tribes of people look discredited, or in talking over them.

I have good friends who are members of groups, like Ordain Women or Mormon Women Stand or Big Ocean Women or other groups. Those groups do a lot of good in terms of the causes they espouse and the values that motivate them. All of those groups display Mormon women’s desires to act on the teachings of the gospel, using the tools we have to try to make the world or the Church a better place. I just think that we could do a better job, generally speaking, of making space for each other in the pantheon of Mormon women.

A positive example of making space is a recent dialogue posted by Gina Colvin who is the podcast editor of A Thoughtful Faith. She just did an interview with Carolina Allen who is the head of Big Ocean Women. Gina is more on the liberal side of feminism: egalitarian, progressive, postcolonial. Carolina is a feminist too but is on the side that people would usually call more conservative, traditional, domestic, etc. That interview is an example of the kind of conversation that we need to be able to have more and more, conversations that really include everyone.

Inclusivity can be a very exclusive term sometimes. For example, in the recent Women’s March, it was thrilling to see pictures of all those women all around the world protesting against various forms of misogyny. But what was sad in my eyes is that some women’s groups that were against abortion were specifically excluded from that march.

If we’re talking about women’s power and women’s voices, then all the women should be there. Not just the women whom we think are the “real” feminists. Because who can say who the real feminists are when they’re all women? How can we not honor women’s voices and women’s positions?

So maybe what you’re describing as the ideal is an inclusivity that includes disagreement.

Yes, definitely. And obviously it’s hard for everyone to be in the same room when people are so different. But I feel like we should be able to do it, at least within the Mormon women realm. We have so much in common! We are so weird and awesome!

At A Glance

Name: Melissa Wei-Tsing Inouye

Age: 37

Marital History: Married

Children: 4 kids ages 10, 8, 6, 4

Occupation: Lecturer in Chinese Studies at the University of Auckland

Convert?: born in the church

Schools Attended: Estancia High School, Harvard College, Harvard University

Languages Spoken at Home: English, Chinese

Favorite Hymn: In Humility, Our Savior; I Feel My Savior's Love

Interview Produced by Annette Pimentel