Esther Hi’ilani Candari is an artist and advocate who was raised to love global community and sharing resources with those in need. She finds fulfillment in connecting people with opportunities and expanding representation in visual art.

What’s your bio?

Esther Hi’ilani Candari

I was born and raised in Hawaii. My dad is an immigrant from the Philippines, and he also has Chinese ancestry. My mom is European American, and she grew up all over the Pacific, so she’s definitely not your standard white American. It was a unique upbringing that exposed me to different cultures, a lot of different perspectives on the world. We traveled a lot and lived overseas when I was in high school. At a young age, I developed a deep love and fascination with different cultures and different ways of communicating ideas and expressing yourself, and an awareness of environments where this kind of variety was scarce.

That awareness was brought into sharp contrast during my mission, in Utah, while working with immigrant and refugee populations. It was a wake-up call of how American the Church can be in the way that it’s administered. I’d experienced a very international church at the ground level but realized that while the individuals in the Church might be international, the approved materials often weren’t. So how do we reconcile that and help to create a global culture in a church that already has members all over the world?

Do you have a specific example of this?

The limitation on musical instruments in sacrament meeting was always ironic and funny to me. In Hawaii, everybody plays ukulele, everybody plays guitar, a lot of people sing. It’s a musically rich cultural environment. Piano is not the main instrument, and the organ is definitely not either. I’ve been to so many girls’ camps and firesides where we had guitar and ukulele worship songs, and it was extremely spiritual for me. It’s one of those funny things—in our church, the European perspective on devotional music was imposed on the Pacific culture that had been Christian for a long time and had its own traditions and its own ways of worshiping. Things like this aren’t usually malicious but stem from a lack of understanding of what religious practice can look like while still maintaining the same doctrines. The updates in the new general handbook have loosened this a lot.

What are some traditions from your heritage that you practice that emphasize different parts of the world?

I grew up with more Chinese cultural practices than Filipino in many ways. Chinese culture has a lot of influence in Hawaii, and more things were preserved and accessible than for my Filipino roots. Growing up, we always celebrated Chinese New Year, which has a huge list of foods you’re supposed to eat. It was one of my favorite holidays because we’d have a big multi-course meal with all my cousins. If I was lucky, people would give me a red packet—little red envelopes that adults give to children with cash in it. You could get some good spending money that week. My childhood perspective was that I got basically a double Christmas every year—big, big celebrations with memorable food and gifts. I’ve tried to keep that tradition. I’m the only person of color on my husband’s side of the family, and I’ve handed out red packets to my nieces and nephews a few times, and they’ve given me weird looks.

Being born and raised in Hawaii, people assume that I’m Polynesian and that has caused some confusion with people accusing me of pretending I’m a different race. I was born there. I spent the majority of my life there, so people equate that with being Hawaiian. There’s not a word in American English to differentiate between being from Hawaii and being indigenous Hawaiian, so it can be confusing. People don’t understand how to talk about me because it’s a unique racial and cultural circumstance. The overarching approach to life and the day-to-day cultural practices I was raised with are generally Polynesian. That affects the way I perceive the world, the way I relate to people, the things that I prioritize, the symbols that I have affinity to. I’ve had to figure out how to strike a balance in my professional life, to pay homage to things that are meaningful to me in a way that is respectful and aware of the complicated relationship I have with it being an indigenous culture I don’t have blood ties to.

A broad Polynesian theme that’s big for me is being communal. The idea that it’s your responsibility to share resources with those that need it. It’s very rude in Polynesian culture to eat in front of someone else. If somebody comes to the house, you immediately offer them food. If you’re out eating lunch in the park and a friend stops by, you offer them half of your lunch. When everybody’s doing that, it’s sustainable—you’ll always be taken care of because you take care of other people. This ties into the gospel mentality of how we should approach the world, being service-minded and consecrating our work to the betterment of the community.

What was your art education, and how does art play into your global perspectives?

Both of my parents are very creative—they met in the art program at BYU Hawaii. In high school, I thought it wasn’t cool to do what my parents did, so I planned on studying marine biology. I thought, “That’s much more serious than being an artist.” While taking a class during high school at the community college, I had an early-life crisis. I realized that scientists mostly spend their time in labs, writing boring reports. I had to ask myself, “Is this what I want to do for four years of college and potentially for a career? What do I enjoy enough to dedicate myself to make the most out of my education?”

It was creating things. I love building stuff. Growing up, I made rabbit hutches for pets, tree forts with my brothers, and little home renovations with my mom. I love working with my hands. I love coming up with creative solutions, making things beautiful and practical at the same time. Sculpture fulfills all of those things—it’s a hands-on art form, and I could tap into some skills I’d already developed. So, I started college pursuing a degree in three-dimensional art.

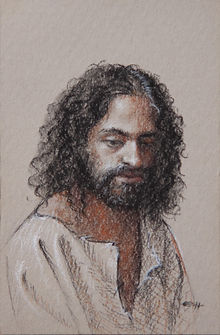

Sketch by Esther Hi’ilani Candari

Then, I served my mission. When I came back, they had discontinued the sculpture program at BYUH, so I had another early life crisis—do I switch schools or switch majors? I prayed and cried a lot and felt strongly that I should switch to painting. I had never painted before, other than some basic watercolor projects in high school. I was a fish out of water but felt strongly that was what I was supposed to be doing. By my senior year of undergrad, I kind of felt like I knew what I was doing and that it was going to be okay. But it took a year and a half to even begin getting there. I still have days when I think, “I have no idea what I’m doing.”

Painting was something I never would have picked of my own accord, which is the story of God in my life. They know I’m stubborn, and I get dragged kicking and screaming, and I ended up really enjoying it. I can look back and laugh at it now, but at the time, it felt like the world was shifting.

My bachelor’s is in painting, and I double minor in sculpture and photography. I did a residency at the New York Academy of Art, checked the box as an art student in New York for as long as I could handle it. New York is not my speed, but it was a good experience for the summer—I made great connections, and learned a ton, and spent so much time with museums. I did my graduate degree at Liberty University, a big Baptist school in Virginia, which was a fascinating experience. I don’t know if I’d make the same decision if I could go back, but I’m grateful for the things that I learned from being there.

During the first summer of graduate school, I did an internship with Joseph Brickey and helped him with the Rome Visitors Center mural. It’s the landscape behind the Christus statue. Sadly, I didn’t get to go to Rome because it was painted in Utah. I spent a summer in a very hot warehouse in Orem, but I can say that a painting I helped with is in Rome. Every time they use it in church photos, I go, “oh, I painted that tree.”

My husband and I met online my first year of grad school on a little app called Mutual. He was doing a PhD at BYU, and I was obviously in Virginia. We flew back and forth to visit each other for about six months before we got married, and he moved to Virginia with me. He took a sabbatical from his program because he could do that, and I couldn’t because I was on scholarship.

My last semester of grad school was spring 2020, and when I finished school, we moved to Utah. I never would have picked to move to Utah. I served my mission here, I thought, been there, done that. I’m not the biggest fan of the weather, not the biggest fan of the culture. But it’s where I’ve needed to be to accomplish what I have. I’m really grateful that I’m here now, even though it was not how I envisioned my life ten years ago.

Are you involved with the Instagram account called Meetinghouse Mosaic, working for diversity in Latter-day Saint art?

Tangentially so, I function as an unofficial advisor consultant for them. I’m not officially part of the organization, but I do work very closely with them. I’m very involved with helping organize their February 2024 show of diverse images of Christ.

Am I Not Hannah by Esther Hi’ilani Candari

Visualization is a huge part of conceptualization of anything religious, especially a deity. Our doctrine as Latter-day Saints is that we are all alike unto God, all races are created equal, gender is created equal. But if we’re not depicting that, it’s hard for people to fully internalize. That doctrine has not been taught accurately through portions of LDS history, so we have a lot of work to undo the harm. In the past, it was taught that black skin was lesser and white skin was more divine. Many well-meaning people in the church don’t even realize that was taught. They’re younger, or they were never exposed to it, or they were lucky enough to not be in congregations that focused on that false doctrine, so they don’t recognize how it subconsciously permeates our culture and how many people of color have internalized some of those ideas regarding their own divine nature, their own worth, their perception of even just their beauty.

I think everyone deserves to see beauty in themselves. There’s great power in beauty. Aesthetics are a huge part of our spirituality. That’s something I see a lot as an artist. While we live in a church that preaches the fleeting nature of mortality, we also live in a church that invests millions of dollars into making temples absolutely beautiful places. Clearly, there is some degree of understanding of the connection between aesthetics and spirituality. Understanding how that functions for people on an individual level is really important, but I think it has been underserved in our public, communal consciousness.

What did you study during graduate school?

We’ve talked about the importance of race in art representation, but I feel equally strongly about gender representation in religious work. I focused on integrating academic theological, sociological, and historic research into paintings. I want to help people reframe how they literally visualize the role of women in our religious spaces and narratives. We often put them in boxes with how we talk about and paint them in our culture, because humans are creatures of habit. When we see something painted one way, or hear a story told one way, we assume that’s the only way to paint or tell that story. In our church, we aren’t always the most academic with our approach to especially biblical studies for various reasons, so people aren’t given a lot of opportunity to question preconceived narratives.

It’s been a little bit heartbreaking sometimes, but also exciting to be speaking at a fireside and take a complicated story like Bathsheba, or an under-told story like Huldah or Deborah, and pull it into the light and pick it apart in a way that helps women to see the empowering narratives within the stories, and wrestle with the complexities in a way that is not denigrating to women and ultimately points to Christ. I’ve found so many women hungry for this, even women who appear to be completely satisfied with their understanding of scripture or their participation in church. There’s often an unrecognized or unspoken hunger to better connect with femininity in the narratives, and in the theology we’re teaching and practicing.

How do you paint a story to shake things up and introduce a new perspective?

My MFA thesis focused on stories of infertility in Judeo-Christian religions and how those stories are told both narratively and visually. My secondary research was current data on the experiences of infertile women in modern religious communities—how many women experience infertility and compounding factors for mental health in those circumstances. I also looked at the theological evolution of how infertility has been taught, especially in Christian circles, the explanations surrounding both fertility and infertility in those traditions, and how they affect modern-day narratives even in Latter-day Saint culture.

As Grains of Sand Sarah and Hagar by Esther Hi’ilani Candari

I think a lot of people don’t realize how much of our theology we inherited and take for granted. It continues to be refined, and purified, and restored, but there’s still a lot that we got as a hand-me-down from the Protestant Reformation, such as the idea that women who have lots of children are blessed. In my research, I came across a quote from Martin Luther. Most people have an idealized view of Martin Luther, and I believe he was a person who did amazing things for the history of Christianity. But like anyone, he had some views that we definitely don’t agree with in our modern church.

One of his theological views was that women are the source of original sin and are therefore responsible to atone for that original sin through childbirth. If a woman dies giving birth, it is an atonement for her being a woman and the source of original sin. When I share that in firesides, it’s a shocker line, but it’s a good wake-up call for people to realize that one of the main fathers of modern Christianity was actively teaching things like that. And even though we don’t teach that directly, those ideas and ideals still permeate our culture.

I also did some primary research with a survey of Judeo-Christian women who experienced infertility, asking about their experience in their religious community and how they did or didn’t connect with art. I specifically asked about the narratives—stories told in their Sunday schools and women’s groups, and if art either supports their experience positively or adds to the pain of being infertile in pro-natalist communities. A strong majority felt they had never seen art they could connect with.

That correlated with another set of primary data that I collected—databases of some major art museums and online art databases, such as Deseret Book, that categorize paintings of women in the Old Testament who experienced infertility: Hannah, Sarah, and Rachel, and Elizabeth in the New Testament for good measure. I looked at what part of their lives the paintings were about: having a child, not about experiencing infertility. That reflected the data from the women that I interviewed—they felt that the full focus was on the solution to infertility of having a child. The missing piece is understanding and finding meaning in the experience of infertility and finding value in themselves in spite of it, or even through it.

So, I painted a series of three paintings depicting that time of Sarah, Rachel, and Hannah’s lives—when they were experiencing infertility. I explored the complexity and pain of their lives in a way that, based on the data I collected, was almost never touched on both in spoken narratives and in the painted narratives and communities surrounding these stories.

What was it like for Sarah to be promised by God that she would have a child, and then spend years watching Hagar birth and raise that promised child? What was like for Rachel and Leah and the constant “the grass is greener on the other side” dynamic they had? For Hannah, I painted the scene at the temple feast when it came into focus that she was one of two wives, and she was childless. Her husband went up to her and said, “Well, I love you, and aren’t I as good as ten sons?” … the typical loving husband who completely misses the point and doesn’t fully conceptualize the female experience in this pro-natalist culture.

We all do that to some extent, fertile women to infertile women, in many ways. I was trying to bring to light these aspects of the stories that are prevalent in the scriptures but are uncomfortable. We don’t talk about them. We don’t paint about them. I’ve talked to women who see these paintings and read my research, and their response is, “I’ve experienced this thing as a woman with infertility, but I’ve never felt like there was a sacred space for me to talk about or to experience these things within my religion.”

What are you doing now in Utah?

Of the Barren and Fruitful Rachael and Leah by Esther Hi’ilani Candari

My technical title is Director of Programming at Writ & Vision, an art gallery and bookshop in Provo. We’re a small company, there are three of us who run it, and we’re all part-time. We have areas that we focus on and overlap as needed, as people are traveling or sick or whatever. I’m mostly focused on developing community relationships, finding opportunities to get the gallery out to conferences, or partner with other organizations. We’ve discovered that we appeal to a niche market, and it’s not efficient to market through traditional means. The best way to connect with our potential audience is to partner with other organizations that are trying to reach the same audience, so we cross-pollinate each other. We’ve done things with the Arch-hive, Dialogue, and BCC Press. Right now, we’re doing a ton of stuff with Faith Matters. I also on the board for Faith Matters, so it’s a nice crossover to provide access to the art world for Faith Matters, and a lot of opportunity for the gallery through them. We function kind of like a nonprofit, and in some ways, that’s why we’ve been able to stay afloat in a market that is not easy. We care about the community, and the community cares back.

It’s hard to describe my job because I’ve kind of created my own. A friend said he describes himself as an “orchestrator” and that’s how I feel too. I’m connecting people with people, and connecting opportunities with people, and connecting resources with people, trying to get all the right things in the same space at the same time to have the best outcomes. Sometimes that’s glamorous, and sometimes it’s not, but it’s really fulfilling. I recognize that without those connecting links, the opportunities would never materialize for authors and artists who wouldn’t otherwise have access to platforms. It’s fulfilling to see a young artist, or female artists, or artists of color sell a piece in the gallery for the first time, knowing that they wouldn’t have been able to get into one of the other galleries. Galleries are weird—you have to have experience to get experience. We’re the gallery that tries to give people experience, and we have no hard feelings if they move on to a bigger, more prestigious gallery. We’ve done our job because we know they couldn’t have gotten there without us.

What I’m hearing through our conversation is that you’re taking all of these different pieces and connecting them together. How do you then connect all of these pieces into your faith and into your relationship with God?

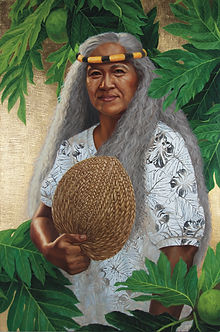

Painting by Esther Hi’ilani Candari

The reason I do these things is because of my faith. It’s not about connecting secular practices back to my faith. My faith informs the more secular aspects of my life—the reason I care so much about social justice, about representation in the arts is because I believe to the very roots of my soul that every human is valuable, that every culture is valuable, and everybody benefits from understanding that they are a child of God. They are made in the image of God. They have inherent value, inherent beauty because of that. If I see any lack in that understanding, I feel like it’s my responsibility as a person of faith to help spread that truth. My research and art are missionary work—I am striving to teach the pure doctrine of the eternal plan and help God’s children through what I’m doing.

Some things I do might seem like they don’t connect. But at the end of the day, everything always connects back, even when I’m stripping floors and repainting them at the gallery, so we have more and better space to showcase art. The art helps people to connect with eternal truths. Even when we’re showing art that seems secular, the pure experience of experiencing beauty and the creation of another soul, there is a glimpse of God in that.

I think there is great significance that one of the first terms used for God is Creator. God is first and foremost a creator. When humans exercise their creative capacities, it is a shadow of the Divine. When we honor that and share with each other, we are honoring and recognizing the divine in each other.

At A Glance

Name: Esther Hi’ilani Candari

Age: 29

Location: American Fork, Utah

Marital History: Married

Children: 2 dogs

Occupation: Artist and educator

Convert to the Church: No

Schools Attended: BYUH, NYAA, New York Academy

Languages Spoken At Home: English

Favorite Hymn: Be thou my vision

Website or Social Media You Would Like Featured:: https://www.instagram.com/hiilanifinearts/?hl=en

Interview Produced By: Trina Caudle