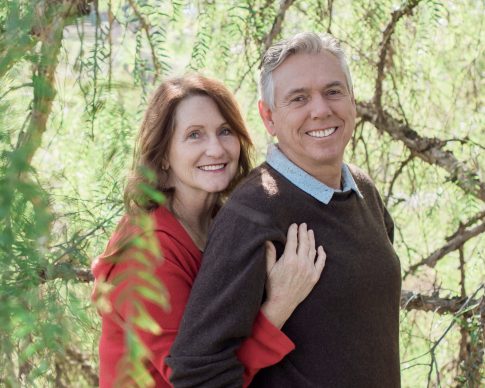

May is Mental Health Awareness month. Fiona Phillips and her husband have supported multiple family members experiencing mental illness. Their experience is being put to good use as they serve as Area Medical Advisor, supporting the health needs of full-time missionaries in California.

Tell me about yourself and your family.

Fiona Phillips

I am currently serving as a senior missionary, living in Vista, California. My husband is retired from his profession as a physician, and for our assignment, he is the Area Medical Advisor and I’m his assistant. We help to coordinate medical and mental health care for all the missionaries in the southern California area. We work with nine missions – the mission health councils, the mission leaders, the mission nurses, and mental health professionals. It’s been a wonderful experience. We’ve really loved it. It’s wonderful to know how well the Church takes care of the missionaries. There are so many things in place to monitor the health needs of the missionaries and we feel blessed to be a part of this process.

At one point, my siblings and I had been sharing the care of our father who had dementia, but when my sister and her husband were called as mission leaders in Chile, we decided it was best for Dad to stay with us. After Dad passed away, we received a mission call to New Mexico but six weeks later, my husband’s mom also received a diagnosis of dementia. Our mission was postponed and we moved to California to take care of her.

We previously lived in Cedar City, Utah for 22 years. We have five children and twelve grandchildren. We don’t live close to any of them except one son, and we’re very happy that he and his family recently moved nearby. We wish we could have them all nearby! But with the miracles of modern transportation and Zoom calls, we stay in close contact. We visit a lot and they visit us a lot.

I’m also an artist. I used to teach drawing, painting, and art history at Southern Utah University (SUU). I also taught high school and junior high school art. Now I’m a studio artist at home. I paint professionally, I sell my work, and show a lot.

What types of mental health challenges, in addition to your parents’ dementia, have you worked with and supported?

My daughters all suffer from anxiety and depression. Other things have come into play too – childhood insomnia, complex PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) brought on by childhood trauma, suicidal ideation and eating disorders. It’s a lot. I’m so proud of my daughters and their intentional efforts to heal. They are amazing, intelligent and beautiful! But life has definitely taken a turn that I never expected or thought would happen when we were first having children. You learn and you grow, and you adapt and do the best you can.

What are some specifics about how your own life has been affected by other people’s challenges, who are close to you?

Fiona Phillips with Grandchildren

When my children were young, I don’t think I even knew what mental illness was. I was quite an idealist and I thought that if I did everything I was supposed to – if I fulfilled my callings, went to the temple, had family prayer and scripture study, the whole bit – then everything was going to be fine!

It was a rude awakening when my children started exhibiting behavior that was troublesome in one way or another. To be honest, I struggled to cope because I didn’t understand. Some of the consequences of their choices were difficult as well. I went through a period of self-blame that wasn’t healthy. I still have those feelings from time to time – sometimes I wonder if they’ll ever fully go away, but I know now how to manage them. But it affected our family relationships, and it still does to this day.

Our daughters have all received counseling. My husband and I have been to counseling ourselves for help in dealing with some of these trials, and also to learn how to better help our children and our aging parents. We’re not trained professionals – we’re just parents, a daughter, and a son. We pray and fast and go to the temple, but we need professional help as well.

My husband has been with me through this whole process. I think we have leaned on each other at different times – sometimes he’s been my support, sometimes I’ve been his. That’s been a wonderful thing, I just appreciate him and his wisdom and his courage.

All these experiences have prepared us for the mission we’re serving, which came about in such an interesting way. Heavenly Father has placed us here in a miraculous way, I truly believe that.

What are some things you do for yourself to maintain your own mental and emotional strength?

Fiona Phillips & the Fifty Faces Project

Mental health challenges have been in our family for 25 years. It’s not been a short experience, in part because of the different ages of my daughters and when they started to exhibit symptoms of illness. Their therapy and other treatments have happened over a long period of time and are still ongoing. So there are things I did at different points during this extended time period.

At first, I tried to put more effort into everything with church and callings and family. Funny enough, I started walking early in the morning with a good friend who was in the Young Women presidency with me, and she also had some struggles with her teenage boys. Walking every day and chatting with her was really therapeutic. Having a good friend is important, if you are lucky or blessed enough to have that.

One thing I did was go back to school – through distance learning, I got a Master of Arts in Humanities and a Master of Fine Arts through the Vermont College of Fine Art. It was something completely different to focus on. It was also a way for me to work through some of my grief, especially when my mother died.

I was teaching at SUU, and we had sold our home and were living in a rental in anticipation of moving to North Salt Lake. Our youngest daughter was struggling and moved home with us, and we were also caring for my father. A year later, we moved to North Salt Lake. A couple of years later, with my daughter in crisis and diagnosed with a mental illness, I began the Fifty Faces Project.

What is the Fifty Faces Project?

Fifty Faces Project

We started attending support groups and classes through NAMI (National Association for Mental Illness), a wonderful organization to help people like us and those who suffer from mental illness. My husband and I began to realize just how prevalent mental illness is. Statistically, one in five people – including children and adolescents all the way to senior citizens – suffer from some form of mental illness.

I decided to paint fifty large-scale portraits. The smallest is three feet by three feet, the largest is four and a half by five and a half feet. The paintings are just of the faces. The models were friends, family members, acquaintances, acquaintances of acquaintances, even some strangers. I did them all in less than two years, so it was an intensive project.

I was thinking, “With fifty in my group of models, possibly ten of them are suffering from some kind of mental illness.” I painted them the way they actually look, like everyone else, because I wanted to erase the stigma. I wanted to open a conversation about the stigma of mental illness and how we’re so afraid of it and of people who are struggling. So I painted them so you can’t tell who does or doesn’t have a mental illness.

At the very end of the project, I sent an email to all the models and asked if they would share their experiences with mental health – whether it’s themselves personally, or a close family member or friend, or as a caregiver. The responses that came back were touching and heartrending and humbling. The stories were presented in a slideshow with music and photography that was projected during the installation of the Fifty Faces exhibit at Dixie State University and also at Art Access Gallery in Salt Lake City.

That was very therapeutic and my family supported me wholeheartedly in this project, even though it was very time-consuming because they wanted me to get the word out.

So the models weren’t sought out as people with mental health challenges, it was just random selection and you figured that ten had connections to mental illness. How many did?

More than I expected. Mental health is so misunderstood. When someone’s behavior is outside the norm of what we consider proper and good, they can be labeled and ostracized. We’re asked to love everyone. We need to understand more about how the brain works and that the process of getting healthy is a long one.

What if someone wants to know, How long is long?

I would tell them that’s not the correct way to look at it. They need to be patient and educate themselves as to the specific diagnosis, symptoms, and treatments. In my mission experience, we see a lot of missionaries that have troubles with anxiety, depression, perfectionism, a lot of things – there are many who get better with a few counseling sessions and sometimes medication, and they do great. The ones who have underlying or past trauma in their lives – they are going to take longer. If it’s a diagnosis of a more serious complicated disease, it may take a lifetime of management.

So I would counsel them to get educated to understand the disease and learn how to help their loved ones get the best treatment that they can. It’s a three-pronged remedy – counseling, medication, and other therapies. There are many therapies.

Getting educated is one way for family members to support a loved one in a mental health challenge. What are other suggestions?

Acceptance is huge – to realize that mental illness is not because of something they’ve done wrong. It’s maybe something that was done wrong to them, but they didn’t do anything wrong to get this illness. That’s another stigma. Mental illness is an illness, like any other disease. It’s an illness of the brain. We have illnesses of the heart or the lungs or other different things in our bodies. We look at those and say, “Oh, someone has heart disease.” We don’t ostracize them and there are strategies to help them get better.

Fiona Phillips with her family

There are also strategies to help people with mental illness get better. I advise that people get counseling earlier rather than later. One of my daughters has three adopted children – she was very proactive about having them see counselors when they were quite young, to help them with separation anxiety and some of the other struggles they came with, and it has really helped them.

If the counselor doesn’t fit, try somebody else. That’s an interesting dynamic – the patient/therapist relationship. It has to work both ways. It doesn’t necessarily mean that the first one you find will be the one that works.

We need to communicate often with the person who has mental health challenges, even though it’s sometimes difficult and painful. It’s important for them to know that you love them unconditionally, and no matter what, you’ll always be there for them. It doesn’t mean that you accept bad behavior, and there are times when you need to set boundaries. But make sure they know you’re always there and you’ll always love them.

Is there anything you did or said at any point that you wish you hadn’t, and what did you learn from that experience?

As my children grew through their teenage years, I knew they were troubled. I tried so hard to talk to them and get them to talk to me, but I couldn’t figure out what was going on. I tried everything I could think of, and they just wouldn’t ever open up. It has come out only recently that they couldn’t get past the fear of disappointing us because we had such high standards for ourselves. The fear of being shamed was just too great.

If I could do it over, I would have done something different in trying to learn how to communicate with them better. Maybe counseling to learn communication skills or how to put them at ease. That’s something I would love to do over.

Right now, we are going through the Dialectical Behavior Training workbook in solidarity with our daughter – it helps a person to reprogram their brain to process information in a different, more positive way, rather than a negative, detrimental way. One of the things I’ve just been learning about is the behavioral principle of “radical acceptance.”

So when you ask what I wish I would have done differently, I am at a point where I am trying to let go of that and realize that I can control today, how I feel and how I think today, and I can look to the future. I don’t have to keep beating myself up about the past. So I’m going to practice radical acceptance right now.

How do you define “radical acceptance” and put it into practice?

Fiona and Doug Phillips

I have my workbook open to this page: “Being overly critical about a situation prevents you from taking steps to change that situation.” You can’t change the past. If you spend time fighting the past or wishfully thinking that your emotion will change the outcome of an event that’s already happened, you’ll become paralyzed and helpless. Then nothing will improve.

So the other option is radical acceptance – to acknowledge the situation, whatever it is, without judging the events or criticizing yourself. Instead, try to recognize that your present situation exists because of a long chain of events that began far in the past, and basically refocus your attention on what you can do now.

So it’s definitely connected to mind focus, bringing you to the present and being mindful of what’s going on at that moment. Radical acceptance is a little more broad than mindfulness, because mindfulness wants you to be in the moment, but it’s a very similar thing. It helps to calm you, let go of guilt, and move forward in a positive way, which is important when you have a lot of things in your past that are sometimes eating you up.

From your perspective of experience, what is some advice for someone at the beginning of the road of mental illness?

Number one, honestly, is that we need to have an awareness that the predators of children are most often family members and friends. Ninety-three percent of the time, children know their abusers. That just goes to show that we can’t just think everyone is going to be good to our children. Be proactive in protecting your children – be very careful who you leave them with and whose house they’re going to when playing with other children. I was not aware of that. But radical acceptance – I’m trying to deal with that positively.

And we have a gift! The gift of the Holy Ghost, and I do believe that gentle guidance is truly a blessing. This life is long, and it’s so hard to watch our children suffer. But we can trust in the Lord’s compassion who suffered everything for us. Even though we were blindsided by our children’s abuse and illness, I have felt the Savior’s love and grace in countless ways.

The other thing is: there’s just so much education available. I go back to that a lot because it’s really important. On the Church website, there’s a lot of great material. That’s a good place to begin, and then you can branch out to other trusted sources like NAMI. That’s where I would start.

What are the challenges you see in the stigma about mental illness, and how do you think they can be overcome?

Talking about mental health challenges is uncomfortable for a lot of people, and it can be uncomfortable for those of us who are in the middle of it. But talking about it is the best way to find solutions. I do believe that we’re talking about mental health more at church than we ever have, and it’s wonderful and I hope it continues. I think it will.

The relationship of childhood trauma and abuse to mental health is so common, but that’s another thing we don’t talk about because it’s too difficult. People don’t want to believe it’s that prevalent. People who have had it happen to them feel ashamed, including at church even though shame is not anyone’s intention – it’s an internal thing. I think if we could be a little more open and welcoming and love the way Christ wants us to love, things could change. That’s my hope.

The stigma about mental illness not being real – we encounter that on our mission. Sometimes a missionary needs counseling or medication, and their family says, “No. It’s not real, there’s no such thing. You just need to work harder.” But for someone who has a mental illness, no amount of “working harder” is going to cure that. Sometimes it just makes things worse. We’re hoping that people’s perceptions about mental illness will change – not just in the Church, but in the world.

There are so many different kinds of therapy. There’s cognitive behavior therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, talk therapy, EMDR (eye movement desensitization and reprocessing) therapy, (that really works, by the way), and in very serious cases, electro-convulsive therapy. They’re also starting to do therapy with some medicine that was previously considered taboo in our society, but when under medical supervision, it has proved to be helpful in some cases. That’s further down the road, more of a last resort. But it’s something they’re continuing to research because it has possibilities.

The last thing – we need to help people understand that it’s a chronic illness so we can’t ever give up. We don’t give up on somebody who has chronic emphysema or cancer. We love them. It’s my hope that we think of mental illness in this way. It changes the way we think of and look at people.

How has your faith helped you through all of this?

Fiona Phillips

I had an experience that is sacred to me, but in this context, I think it’s appropriate to share. I increased my temple attendance. I was driving to the St. George Temple and praying and crying and praying and crying. Along the way, I heard a voice clearly saying, “Be still and know that I am God.” That changed my thinking in a very significant way. Up to that point, it was, “What do I need to do more? What am I doing wrong?” It was about me and how I could help others. I wasn’t letting Heavenly Father do His work in their lives.

Doing what we can is important but I don’t think I was allowing Heavenly Father the space to do what He needed to do or being patient to let that work in someone else’s life. We need to trust Heavenly Father that He can affect change that we can’t. That was a big lesson and I’m so grateful for it.

We also need to let go of our personal guilt. There’s nothing healthy about guilt – it does nothing for us. We need to give our guilt to the Lord and let Him take that from us. That is part of the Atonement. Heavenly Father sent the Savior to suffer all these things for us so He would know how to succor us. We put our guilt in this precious little package that we don’t want to unwrap but we want to hold on to it – that’s not healthy and it’s not good for our spirit either. If we let go and let God – as President Nelson says, “Let God prevail” – then the Savior will be able to take it from us and that burden will be lifted and we’ll be in a better place.

We need to trust in God’s mercy and love – that He will not forget our loved ones. He knows them and loves them, more than we could ever imagine. He will help them heal when we put our trust in Him. I truly believe that. My husband and I have seen many little miracles along this path. I think we’ll continue to see them. We can’t get discouraged when things may bottom out again, but it’s okay, it’s part of the process of becoming more like the Savior. We can trust in God’s mercy.

At A Glance

Name: Fiona Phillips

Age: 68

Location: Vista, California

Marital History: Married

Children: Five

Occupation: Artist, Missionary

Schools Attended: MFA, MA, BA

Languages Spoken At Home: English, and some Spanish

Favorite Hymn: Where Can I Turn For Peace

Website or Social Media You Would Like Featured:: http://fionabphillips.com

Social Media: @fionaphillipsartstudio

Interview Produced By: Trina Caudle