Listen to this interview at the Mormon Women Project podcast, available on all platforms.

Emily Bates suffered severe migraines from a young age, leading her to pursue a career in science in order to study the genetic causes of the condition. She now is an associate professor at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, and runs a lab studying the molecular mechanisms of birth defects. Emily has led groundbreaking discoveries in the field of genetics, overcoming dyslexia, cultural pressures, and self-doubt along the way. She feels that God has led her from the beginning down this path. Emily sees science and faith as compatible methods of seeking truth, and relies on both as she runs her lab, partners with her husband to raise their daughter, and works to understand the nature of God and of the human body.

I don’t know if layman’s terms exist for what you do, but can you explain what your current work entails?

Right now I study how the brain forms and how the face forms—so birth defects that include brain malformations or facial abnormalities like cleft palate, cleft lip, or a smaller jaw. We use human mutations that are identified in people with these birth defects to try and uncover how things happen normally, and then to understand what goes wrong when there’s an abnormality. Usually that entails identifying a mutation that exists in humans who have these kinds of birth defects, and then putting the gene with the mutation into a mouse, or a fly, or cells.

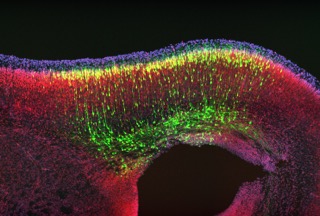

An image of a section of mouse cortex (a region of the brain) stained to look at migrating neurons, taken by Emily’s PhD student, Dr. Jayne Aiken.

How do you change a fly’s genome?

Fruit flies and mice have mostly the same genes that we have, just fewer of them. All of the genomes have been sequenced for flies, mice, and humans. (Not all of the human population is sequenced, but we know what a general human genome looks like.) So we can find a similar gene in a fly, for example, and we can edit it. One of the things that you can do in fruit flies is just inject an egg (or eggs) with DNA that’s encoding what you want it to, and then that can get taken up into the fly’s genome, and then they just pass it down into their progeny. We’ll put some kind of genetic marker to let us know that it got incorporated into the fly. These genetic markers are visible, like an eye color marker. The process is fairly similar for mice, but you have to implant the embryos into the uterus of a mouse, similar to in vitro fertilization. I don’t do either of those myself; we design the DNA, but we send it to a company that actually does the injection.

I’m trying to picture a syringe small enough to inject a fruit fly egg…

They are tiny.

So why birth defects? What led you down that path?

This is not where I thought I would end up. I started out in high school wanting to become a scientist, and I wanted to do research on how migraines happen using genetics, because I suffered from migraines really severely and frequently. So when I started at the University of Utah I applied to a women in science program called the Access Program. They picked twenty female students who had interest and aptitude in science, and then gave us a summer-long course that included computer science, chemistry, physics, math, and molecular biology. We also got to enroll in a research lab as soon as we started college. I was placed into a genetics lab because I wanted to study the genetics of migraines eventually, but no one was studying that at the time. The lab I got into was studying how birth defects happen using fruit flies, and I loved the research and I really had a great mentor. Her name was Dr. Anthea Letsou (she’s still at the University of Utah). I really loved research. I presented my research as an undergraduate, and I gained a lot of confidence from that mentor.

I grew up in a family where my older brother was really a genius, and I am dyslexic. When you’re a little kid, you kind of define smartness by reading, and since I was slow at learning to read and my brother was really fast and amazing, that defined me. I always knew I was a hard worker, but whether I had aptitude was always in question for me. Then I got into this lab and was successful, and my mentor really valued my contribution. At the end of college she told me that I should apply to all of these fancy fellowships, and also that I should apply to the top graduate schools in the nation. I thought she was a little bit crazy to have that kind of confidence in me, but I still took her advice and I applied to a bunch of schools that she had recommended for me: Harvard graduate school, Harvard medical school, Berkeley, UCSF, UCSD, so basically the top-tier schools. Then I also applied to schools I thought were more realistic to me, but it turned out I got into all of them! And they pay your way, so that was kind of an amazing thing for me.

Emily with her grandma, upon finishing her PhD.

I wish I had taken that as a sign that I belonged, but I still had a lot of confidence issues that I think did cripple me in graduate school a little bit. I still worked hard, and I started doing neurological studies, working on Huntington’s disease, which is a neurodegenerative disorder that is completely genetically inherited. That got me a little bit closer to my goal. I studied ion channels also, which is a type of pore in cells that regulate the electrical properties of brain cells, called neurons. So it was in graduate school that I started working on how the brain works and doesn’t work. And then in my post-doctoral work I really did get to follow my long-term dream which was to study the genetic causes of migraines. I joined the lab of Dr. Louis Ptacek at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), also a top medical school in the country, and research facility. There, I was introduced to someone else’s project, studying a very, very rare syndrome caused by mutations in these ion channels that cause periodic paralysis, differences in heart beats (arrhythmias), and cognitive deficits as one might expect, but also birth defects like cleft palate.

I had never read anything in any developmental textbook or article that said that ion channels, which usually work in your brain or your muscles, influence the way your body forms in utero. This seemed like a big mystery to me that was completely unsolved, and it also seemed like I was in a really good position to answer how this happened because I had studied how the brain works and also how development works and I spent a significant amount of time doing both. When I started my career as a professor at Brigham Young University, I started two projects in my lab. One of them was following up on the genetic causes of migraines and the other was studying how these ion channels that regulate electrical activity in your brain and your heart and your muscle could be influencing how your palate develops as a person when you’re in utero (because that’s not something that normally people think of as having electrical activity). So that started the whole project of studying birth defects, and what we found was that these ion channels regulated how developmental signals are sent from one cell to another to tell that cell what to become. That was a really big discovery and really exciting for me, so that project took off and the migraine project kind of fizzled. When I moved to the University of Colorado I was hired by the medical school to do the birth defect research, and so the migraine stuff has been put on the back burner for now. Part of that also has to do with funding. Migraines affect three times more women than men, they affect 30% of the female population and only 5-6% of men. So it’s just not a priority in the funding I think, because mostly older men are in charge. Their priorities are where the money goes.

But I actually really love understanding these rare disorders that are never going to get funded or examined in a pharmaceutical company (because they’re too rare and there’s not any money in it). The only way the type of research I do can be funded is by the government. I do have to say thank you to everyone who pays taxes because that’s what funds all the research into rare disorders, and if you are a mother of a child who does happen to have some of these rare birth defects, you really do want research to go into preventing them and maybe potentially finding a way to cure them. A lot of the developmental processes that we study can also be used for regeneration, potentially. So like if you break a bone, how do you repair it better and faster? Stuff like that.

Did your family encourage you in the sciences? Was that part of your family background?

Yes. My father is a math professor, and he was always very, very encouraging of science and math and educational pursuits. My mother has a masters degree in nursing. She is a pediatric nurse practitioner. So both of them have a strong science background, and both of them were very invested in my education along with the education of my siblings.

I credit my mother with most of my success because if you can’t read, you can’t do really anything in science either. She spent hours and hours and hours reading with me—reading every other sentence, then reading every other page, so that the stories would move fast enough that I didn’t get completely bored. She was really strict. It was a requirement for me to practice reading every day, until eventually I could read (I think) pretty much average pace. That’s because of my exceptional mother. Dyslexia is genetic by the way! My father is dyslexic and so is one of my brothers. But we’re all three professors, so you can get over it with hard work.

Emily with her family. (Photo credit: Robyn Kessler Photography.)

You talked about the lack of confidence that you felt going into these premier schools, and I wonder how much our society or our cultural church messaging about girls and science played into that for you.

That’s hard to parse apart because my upbringing was really intertwined with church. I can’t really distinguish what came from church and what came from my family dynamic. I also think it was really great for me to have this older brother who was so smart, because I figured I had to be as successful as he was, and that just meant I had to work harder. If he had been maybe not so invested in reading and learning and had a great curiosity and did really well in school, I may not have done well in school either, because it was hard for me. I’m really grateful that I followed my brother, even though it probably did contribute a little bit to thinking, “He’s the smart one, I’m the one who works hard, but I’m not smart.” I do know that I noticed when all of my friends switched from being interested in science and math to absolutely not wanting to go into that. It was around puberty, when they started getting interested in boys, and learning that what boys wanted in our church culture was a stay-at-home-wife with children. I do recognize that that didn’t happen for me until much later, but I did have those thoughts. Once I was in graduate school, I recognized that the selection process in our church favored people with different educational goals than I had.

Emily with her husband. (Photo credit: Robyn Kessler Photography.)

Can you share an example of an experience you had with that?

Sure. There were a lot. Some of them would be kind of superficial, like having a conversation with someone that seemed like that they were really interested in me, and then I would say that I was teaching, and they would still kind of keep interest. And then when they would ask, “What grade?” I would be like, “Well, undergraduates at Harvard.” And then, “In what subject?” And when I answered, “Molecular biology,” they would just drop interest. That was a typical thing. Other people would directly quote—and sometimes even physically bring and point to—the Proclamation on the Family, and say, “Women are supposed to be the nurturers and men are supposed to be the providers, so are you willing to give up your career?”

Because you can’t be a molecular biologist and a nurturer…

That was what they were saying. I actually have really bad feelings towards the Proclamation on the Family, just because so many people would point to it saying I was not a worthy or good woman because I had a career goal. It probably didn’t help that it was science and not elementary education or nursing, for example, which are more accepted. But that happened a lot of times. I think it might also be my particular generation. The Proclamation came out basically when my peers were starting to find spouses. So maybe it was emphasized in a way in my particular age group that may not have been for the later time point or the earlier time point, but I know that it affected me.

But it all turned out well. I’m happy now and I’m happy to be with the person that I’m with. He’s always been encouraging and proud of my career, so I wouldn’t have it any other way. But it was painful at the time to hear people saying that what I was doing was not faithful, when it was actually really, really hard and I felt like it was called of God. Actually most of my patriarchal blessing is about my career, and very little of it is about having a family. I feel like it came from God in the first place, and I’m following what he wanted from me. But that just didn’t fit with the church culture.

Emily with her husband and daughter, in front of her husband’s ice cream stand at the Breckenridge Art show. Emily’s husband owns and operates an artisan organic ice cream shop, named after her (Em’s Ice Cream)

You ended up marrying a man who’s not a member of the Church. We recently published a series on mixed-faith marriage, so I’m interested in that story, if you’d like to tell it.

He was definitely the best match for me that I’d ever dated. Part of that was that he was funny and intelligent and we had great conversations, and I enjoyed his company so much. Part of it was that it was really the first time I’d felt like the person I was dating was impressed and proud of what I was doing in my education and in my career. That was so empowering to me, and it felt like I could be me and I could be proud of what I had worked so hard to do. I really had not ever had that in dating. So maybe part of it was that too. I felt like I could be myself and be proud of myself. Getting a PhD was really hard. I love, love, love what I do now, but it’s a hard road. To have other people telling you, “Well, you shouldn’t be doing it anyway. It’s bad of you to have those aspirations, or it’s prideful,” definitely doesn’t feel good.

And the opposite of that is just an amazing thing. I felt like he would be part of a team with me for the first time. He took care of me while we were dating. He cooked for me. He took me to the airport when I went to job interviews. I just fell in love with him. We talked a lot before we decided to get married about how it would work. He’d actually been raised in a mixed-faith family—his mother was Catholic and raised him going to Catholic church, and his father wasn’t and didn’t go to church with them. So he already had a good model of how that could work. He thought it was good to be raised with religion, and he was happy to let me raise any potential children in going to church with me. Then he requested that he also be respected in his viewpoints and that we don’t try to push that on him. He’s always been very supportive. We still pray over meals and now we have a daughter and she knows that’s part of the habit, part of our family culture. I go to church with her, and he doesn’t go with me most of the time.

Emily and her husband. (Photo credit: Robyn Kessler Photography)

Now that you have a family, how has that impacted your work?

I think anyone who has children will tell you that the children become your top priority. I worked a lot harder, I think, before we had a daughter. I put a lot more time into work. I put even more time in to work before I was married, because that relationship also needs nurturing and time. I think the hard work that I put in earlier helped to get me where I am, and now I can be more flexible because I run my own lab. I basically followed the advice of Ruth Bader Gisnburg—she worked I think from 9-4 and when she came home she was completely concentrated on being a mother until her children went to bed, and then she would work again after they went to bed.

So I try and follow that model. I leave work a bit before 4:00 to get to her little school, then I take her home and we play or read. Depending on the day, we get dinner ready together, and have dinner, and read books, and then do our bedtime routine. Usually there’s a game of chase and hide-and-seek in there. Once she goes to bed around 7:00, I usually work after that again for a while until I go to bed. Right now, she’s an only child, and I had her when I was 40, so I don’t know if there will be another child. If I was at home with her all the time, she would be so spoiled rotten, because she’d have all of my attention all the time! She’d never need to learn to share, and I think it would be really hard for me to not spoil her. Being in a little school where she has to share is actually a good scenario for her.

Emily and her daughter.

People often talk about science and religion in mutually exclusive terms, like they’re opposed to each other. You are a scientist of faith, so I’d like to hear what synthesis you see between the two.

I see them both as seeking truth. To me, they’re not at all in conflict with each other, in any way. But that also means that I don’t just accept anything, really, on either front. If the truth from one source is conflicting with another source, then I will try and figure out which one I think is right, or how they could work together. I do think that they are valuable complementary methods.

When I was in either high school or junior high school, I was living in Provo, Utah and I had a Sunday school teacher say that I could not believe in God and also believe in evolution. I had just learned about evolution in school, and the different theories of the origin of life, and they made a lot of sense. I felt like I had seen evidence of evolution in a lot of different things that I was learning about and it was a beautiful theory in my mind. So I was really conflicted, because here this guy is telling me that I can’t believe in God, and I did believe in God, and believe in this theory that I thought made a lot of sense. It seemed like, “Well why would God make everything fit together so perfectly in this theory if it weren’t true?” That just didn’t make sense to me because the God I believe in is a loving God who wants our happiness and who is not out to deceive us. It was actually keeping me up at night.

One night I had been praying, “Please help me to find what’s wrong with this theory so I can be at peace with my beliefs.” I was drifting off to sleep and I had this big impression that I should read Genesis, the beginning of the Bible. So I read it and it was amazing to me how closely it followed evolution. It felt like a personal revelation that was saying, “Actually, these aren’t in conflict at all. If people just read the Bible more closely, they would have come up with it earlier.” Because it’s saying that life didn’t just appear—there was an order to it. At that point, I really did feel like it was a revelation from God that there didn’t need to be any conflict, that basically the Sunday school teacher was not right. You could believe in both. And you should follow truth no matter what the source. Whether you learn it by physical senses or spiritual senses. They’ll lead to the same place if you’re in tune with both, and if you put the effort in to study and learn and practice.

Emily with her family, and chickens.

Does revelation play a role in your current work?

I don’t know! This is a million dollar question. I’ve wondered this, and I’ve asked it in so many Sunday school classes—how do you really distinguish your own thoughts from the Spirit? It’s hard. It’s really hard. I thought I knew when I was a teenager, but since then I’ve had more complicated experiences where I felt like I got an answer from God and then maybe it was just what I wanted. So now, I don’t really know. I kind of think that all good things are inspired in some ways from God. But I definitely need to work to get there, right? So there is effort on my part, and maybe God meets me with that. Certainly I was inspired to follow this career path by my patriarchal blessing, which I think that comes from God.

Emily with her first PhD student at BYU, Dr. Giri Dahal. (Photo credit: Mark Johnston/Daily Herald)

Do you feel that you’ve learned anything about God as you’ve studied the human body and disease and genetics?

I really believe strongly that only good comes from God and nothing bad comes from God. When things go wrong, they just go wrong because of how mistakes happen in biology. I don’t think that God intervenes very much in that. That’s important because there’s a lot of suffering in the world due to disease and sometimes people attribute that to God. They’ll say, “What did I do to deserve this? Why doesn’t God change this or take it away?” I think it can really strain the relationship with God, because if you’re begging him to take away something that’s giving you pain, or giving someone you love pain, and it doesn’t change then you may feel abandoned, or that he doesn’t love you, or that he’s not there.

Studying what I study, I see these mistakes happen all the time. It’s actually a miracle that anyone is born whole without major health problems, because just so many things have to come together at the right time, at the right place. Millions and millions of reactions have to happen precisely correctly to get someone who hasn’t got a birth defect, for example. And on top of that, there are neurological disorders and cancers and all sorts of things. These are all biological processes and I think seeing how it works with science you can see how God just set it in motion, and then is there to inspire and comfort and give you strength to get through the challenges of life without physically intervening in how life happens. That’s the view of God that I have. You can be as good a person as you can possibly be, but that doesn’t mean that you’re going to escape challenges in your health or real struggles with your own body. I don’t really think God intervenes in that very often, or maybe even at all. I’m not sure. But he does always give you strength to get through things and he can send you peace and comfort, and through that you can become a better person even without the challenge going away.

Emily with her daughter.

Have you experienced that personally?

Yeah, I have. My migraines were really, really painful. About 45 minutes before the pain arrived, I would start to lose my vision beginning at the periphery and then moving inward. Then I would get this intense head pain and I still couldn’t see, and I would vomit uncontrollably, and it basically knocked out an entire day. When I was in high school, those could be as frequent as once or twice a week, particularly in my senior year of high school. I never was a time waster, so it felt really unfair to me that I would lose days when some people just gave away days by watching TV. I was following the Word of Wisdom and I was taking care of my body the very best I knew how, and I was trying to be a good person, and I was following the commandments as best I could, and I was reading the Book of Mormon. I was doing everything I could and praying for these to be taken away, and they were not taken away throughout high school, college, my mission, or graduate school. I could have studied really hard for an exam and then I’d get in there and the exam would start disappearing. It was really hard. It was hard socially too. I could never be relied on to do anything because I didn’t know if I’d have a migraine the next day. I remember throwing up in public a lot of times. That’s terribly embarrassing.

I really struggled and asked God for a long time to take the migraines away. I actually read in a novel a conversation that was basically what I just recounted, saying God will give you strength to get through things, but doesn’t always take them away. Then after learning about biology, it seems like it would kind of be breaking his own rules to intervene on that level. Maybe it’s better to just learn from the challenges that you have because of the imperfection of biology, and learn to have compassion and learn to be a better person through them instead of wishing them away, and wishing God would take them away.

Emily at her wedding. (Photo credit: Robyn Kessler Photography)

Is there anything else that you’d like to share?

I guess I would like to share that the reason science is so amazing as a career, is that sometimes you’re the first in the entire world to know something. That discovery process is like being on a mountain top. It is so exciting. There’s almost nothing else like it in the world. I can remember some of the discoveries—we thought something might be the case, we designed an experiment to figure that out, and when we saw that it really was what we thought it was, I remember literally jumping up and down, just dancing in the lab because it was just so cool. That’s happened multiple times. I think a lot of times people think of science as the class that you go to at school where you memorize a bunch of things and then you spit them back. Science is actually the exact opposite of that. It is learning what no one knows yet. Sometimes it actually overturns what you learned in your textbook in your high school biology class, or your college biology class, or even what you thought you interpreted from earlier data. I think the excitement of science is something I would love for people to know. It’s continually learning and continually searching for truth.

At A Glance

Name: Emily Anne Bates

Age: 42

Location: Denver, Colorado

Marital History: Married

Children: One daughter who is 2.5 years old

Occupation: Professor

Convert?: Raised in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

Schools Attended: University of Utah in Salt Lake City, UT and Harvard Medical School/Graduate School in Boston, MA.

Favorite Hymn: How Great Thou Art

Websites: http://www.ucdenver.edu/academics/colleges/medicalschool/departments/pediatrics/subs/DevelopmentalBiology/researchlabs/Pages/Emily-Bates.aspx, and http://www.emilybateslab.org

Interview Produced by Meredith Marshall Nelson