Erica Glenn believes in the power of music and the healing process of creativity, and has seen from experiences around the world how creativity fosters communities. She started composing her own music from a very young age and has written and produced her own musicals, including The Weaver of Raveloe, which was performed at the American Repertory Theatre in Boston in 2014. She also actively uses her music abilities to bless others’ lives, whether it is through performance or teaching. Erica has received her education at Arizona State University, Longy School of Music, Harvard University, and is currently pursuing a DMA in Choral Conducting at Arizona State University.

In the past you have said that you’ve lived a circuitous life. Where did that start?

Probably with my decision to turn down the Hinckley scholarship at BYU to attend Arizona State University as an undergrad. That step of faith (which was difficult at the time!) led to a life of being willing to travel from place to place as it was needed. I’ve lived in Arizona, England, Ukraine, Boston, New York, and Russia for school, a mission, research, and two master’s programs. It’s been an interesting path. Lots of unexpected detours! And now I’m headed back to ASU for a doctoral program.

Something that runs deep in your life’s connections is the thread of music. What started your love of music?

I think there are two answers: First of all, as Mormons, music is in our blood. Whether or not we come directly from pioneer stock, we all inherit the musical heritage of our spiritual ancestors when we join the Church.

My personal love of music stems from my grandmother, who was a concert pianist and my piano teacher. My mom, who has a Master’s in Humanities, is also a great appreciator of the arts, so our home was always filled with classical music. My mom is a remarkable woman; she’s the kind of person who could convince a stone that it had potential! She encouraged all of us to dream big and work hard. She did her best to facilitate our dreams and to model what it takes to push through discouragement and make big things happen.

Erica in a piano recital at age 8

When did you first begin composing?

I was always putting on neighborhood productions in my backyard. I thought I was an adult when I was a child; I really did! In kindergarten, I informed the teacher that I was going to produce The Nutcracker. I brought in costumes and a cassette tape with recorded sections of the music. It was serious business for me.

Around the same time, I remember practicing the piano at home and suddenly realizing, “Hey! I don’t just have to play what others have written. I can write my own music.” I was always experimenting with things—melodies layered on top of each other, instrumental combinations. It’s like my brain is half musician and half scientist, which is useful for a composer. I wrote my first full-length musical when I was 10 and my second when I was 12. The show was based on one of my favorite childhood novels, Dancing Shoes, and I had the privilege of seeing it produced at a couple of theaters in Utah when I was 14.

Erica at age 14 performing as the character Rachel in Villa Playhouse’s production of her original musical, Dancing Shoes.

What an incredible opportunity to have at such a young age. What did you learn from it?

The whole experience lit a fire beneath me. It was a crash course in what it takes to get a new script to the stage. Writing musicals isn’t just about “composing”—it’s about weaving a narrative and working directly with people in a very hands-on way in order to move an audience. There’s something magical and collaborative about creating a “thing” where nothing has existed before—something that makes me feel a closeness to God.

Has it always been easy for you to compose music? Or was there a time when it was more difficult?

Composing was always natural. . .until I got back from my mission to Ukraine. There’s no reverse-MTC to prepare you for the cultural and spiritual shock of returning home. I loved Ukraine. I came away with such a deep love for the people, but it was more difficult than anything I had ever done before. In those early months post-mission, I felt directionless—something I’d never experienced before. I couldn’t rekindle my love of writing music, which was almost scary. I never had to search for motivation or inspiration—it just came. And suddenly it just wasn’t coming.

Erica in St. Petersburg, Russia

What helped you get back into musical composition?

As doors in Utah seemed to be slamming shut, I felt prompted to become a nanny in Boston as I applied for grad schools on the East Coast. It was while I was working for my nanny family that I became involved in Boston’s music scene and decided to pick up an old project—adapting George Eliot’s Silas Marner for the stage. Silas Marner has always been one of my favorite novels; it combines the sweeping themes of a story like Les Mis with the psychological depth of one like The Secret Garden. It’s a drama of epic proportions that somehow never loses its intimacy and humanity—a musical just waiting to happen. I began with a pivotal moment in the book and built a song around that moment. From there the show grew outward organically (which isn’t to say that it didn’t go through dozens—maybe hundreds!—of rewrites). In the end, The Weaver of Raveloe was produced at the New York Musical Theatre Festival and received a fully-staged premiere at the American Repertory Theatre in Boston with Dallyn Bayles in the lead and Melissa Leilani Larsen as my new co-writer.

And somewhere along the way, you got two master’s degrees in Boston?

Yes. My first was at Longy Conservatory in Music Composition, and the second was at Harvard in The Arts in Education. I went back for that second master’s after working for a year as faculty at the Franklin School for the Performing Arts and Dean College and realizing that, eventually, I wanted to open my own performing arts school. Attending Harvard was like drinking from the end of a fire-hose. I couldn’t get enough of the research opportunities, internships, lectures, and community outreach experiences.

What were some of the most meaningful opportunities for you during your time in Boston?

While I was at Longy, I began developing a theory about the therapeutic benefits of singing and Dalcroze Eurhythmics for orphans in Eastern Europe with RAD (a Fetal Alcohol Syndrome disorder). In 2015, a colleague and I traveled to St. Petersburg to explore the potential impact of this approach with Russian orphans. The results were very promising, and we were invited to present our research at the 2016 Western Division ACDA Conference in Pasadena. It was beautiful to see the way past experiences with music, Eastern Europe, and the Russian language were all coming together to allow me to serve others in ways that were meaningful to me.

Another pivotal experience was my internship with Broadway composer Charles Strouse (who composed the music for Annie and Bye, Bye, Birdie).

Tell me how you got that internship.

Well, the summer after my first year at Longy, I wanted to do something that would really move me towards my musical goals, so I started looking into internships. Nothing grabbed me. I took a step back and thought, “If I could craft the perfect internship for myself, what would it look like?” I knew I’d want to shadow a Broadway composer. I decided to be gutsy and send out some emails.

Did you find anyone to email?

Not right away. Big-name Broadway composers don’t just put their information out there. In the end, I ran across a page that was set up for Charles Strouse’s 80th birthday so that people could write “happy birthday” messages. I thought, “Okay, this is probably deactivated, and it’s not even set up for this purpose, but I’m going to write and let Mr. Strouse know how much I loved his musicals growing up and who I am and what I want to do.”

The very next day I got a call from Charles Strouse himself! I almost dropped the phone. He told me that he’d never had an intern before but that I reminded him of his younger self and that he remembered Frank Loesser reaching out to him when he was a young man. I moved to New York, and they paid me a small stipend to do some assistant music directing and transcriptions. It was an amazing, immersive experience. I discovered that once you have an “in,” red tape disappears and connections are easy. I found myself working as a go-between for Charles Strouse and Richard Maltby (who wrote Miss Saigon) during brainstorming sessions for a new musical. It was surreal.

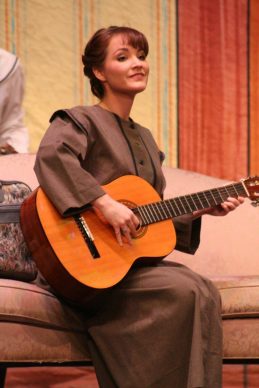

Erica performing as Maria in The Sound of Music (Franklin Performing Arts Company, 2013)

That is incredible! Were you able to find affordable housing in New York?

It was cheapest to live with nuns, actually.

Really? What was that like?

The nuns were very sweet! People think they just stay in the convent, but they actually saw Sister Act when it opened on Broadway, and they were the celebrities of the show (everyone clapped when they came in!). The convent had been converted into a residence hall for girls between the ages of 18 and 25, and I was one of the only Americans. You would come down to breakfast every morning and meet young people from all over the world!

What an education!

It really was! It opened the door for the production of my show at the NY Musical Theatre Festival and led me to the Marvin Hamlisch Broadway Conductors Program in NYC, which was instrumental in kindling my interest in conducting.

How have you seen the hand of God directing the experiences in your life, and how has He used your talents to bless others?

After finishing my master’s at Harvard, for example, I was determined to start a performing arts school somewhere on the East Coast. Then one of my Harvard friends told me about a new school called the American International School of Utah. I wasn’t really interested in moving back to Utah. But the superintendent called me up for a chat about educational philosophy, and after our conversation, he asked if I’d consider building and directing an innovative performing arts department at AISU! I hung up in shock, but I knew already that it was right. All of the logistics fell into place within a matter of days, and I took the job.

Erica dancing at the Bonneville Salt Flats, in Utah

And you were able to use your educational experiences in designing the school and the performing arts department?

Absolutely! Education can feel very theoretical and abstract, but Harvard did a great job of “operating at the nexus of practice, policy, and research.” They were very hands-on. I had already established a performing arts program at low-income community center in Boston, I’d worked as an intern at the American Repertory Theatre, and I’d engaged with the cutting-edge research coming out of Project Zero, so I knew exactly what I wanted at AISU. I was hired as part of the senior management team and was able to have a say in designing the whole school—what it was going to look like, how it was going to function. I thought that would be the most exciting part of the whole offer. I soon learned that working directly with students as the school’s choir director was the truly transformational thing—transformational for me and hopefully for the kids, too. I didn’t realize that the Lord needed to use me in those specific ways at that specific time, but He did.

How has working with the students changed you?

It has given me even deeper insight into what music can do for individuals. I didn’t anticipate that we’d have so many kids with special needs, autism, depression, anxiety, bipolar, PTSD. We’ve had two completed suicides and dozens of attempts. The beauty of our school is that it attracts kids who have struggled in traditional settings, and its innovative structure gives these kids a second chance. Our students were hungry for a safe learning environment, and my choir members bonded instantly. Music has been a literal medicine for these kids. I’ve watched many stop using drugs, start earning 4.0s, apply to colleges, and change their entire outlook on life. The collaborative creativity and success they experience in a choral setting fuels their confidence. They think, “Oh, I can succeed at anything I really put my mind to!” And for a lot of these kids, that’s a revelation.

That is amazing to hear how music has formed such a community at your school. Where else have you seen music form community?

Definitely through our heritage as Mormons. Music has sustained us as a people. Winter Quarters was a bleak place, for example—heavy storms, extreme suffering, malaria outbreaks. 2,000 people died. It’s interesting to me that Brigham Young received very specific revelation there, and part of that revelation was, “If thou art merry, praise the Lord with singing, with music, with dancing, and with the prayer of praise and thanksgiving,” which seems almost like frustrating advice under the circumstances!

It does seem a bit counterintuitive.

Exactly! But I think there’s a reason it was given at that point and not during a time of happiness and plenty. This wasn’t just a suggestion; it was an actual commandment from the Lord–something that was probably meant to help the people survive in a very literal way. Brigham Young recognized that music is an intrinsic part of who we are as human beings. It’s a survival mechanism. It’s so much more than just an outlet or release or form of entertainment.

Erica performing as Mary in “Mary Poppins” (Covey Center, 2015)

That’s beautiful.

I think so too. I also think that music also helps us understand our spiritual selves more fully and gain emotional strength during times of adversity. For the pioneers, music was a potent medicine that traveled easily and cost nothing. And it’s the same for us. Music is equally available for everyone. It’s hard to pinpoint why it is so powerful (although science confirms the bonding and therapeutic effects of singing-released oxytocin). But it undeniably unites us and uplifts us and expresses who we are in an intensely personal way. Music combats feelings of loneliness and isolation in a manner that few other things can. It also helps develop empathy and attention to subtlety and nuance—qualities that seem to be rapidly removing themselves in this world. Across political and racial and economic divides, there’s this lack of empathy which affects our ability to discern between truth and error (in all their subtleties).

How has creativity helped you become more like Christ?

Creativity is an antidote for desensitization. Active participation in the creative process keeps our hearts, our minds, and our ears tuned to the whisperings of the Spirit, which leads us to Christlike love. There are two forces in the world: the creative force and the destructive force. And we all know which eternal power represents which. Our Articles of Faith tell us, “If there is anything lovely or of good report or praiseworthy, we seek after these things.” When I think about the kids in my school, so many of them are subjected to destructive forces at home and in their communities. Some of them have parents that tear them down, peers that tear them down, a world that tears them down, and so engaging in something that is creative is profound and healing. It really is. It’s a miracle. It pulls them back from that destructive spiral and points them in the direction of godliness.

There is something vitally important about learning to create rather than destroy, whether it’s creating strong communities or producing a work of art. Again, I think back to that experience when I was 14, watching a show I had written come to life on stage, creating something that hadn’t been there before. There is nothing more fulfilling, especially if it brings joy to others. When community and creativity come together, there is power.

That’s beautiful. Thank you so much. Is there anything else you wanted to mention or bring up about music, creativity, or communities?

I think one of the wonderful things about Mormon culture is the natural communities that arise from the Church structure. No matter where you go in the world, you’re going to find a ward. You’re going to find people who share your basic values and welcome you with open arms. There is a danger, though: sometimes people can feel lonely when they don’t fit into one of the naturally preexisting communities that the Church has established. Church doctrine celebrates diversity, but Church culture doesn’t always align. Those with divergent political opinions or an unusual life trajectory can feel disenfranchised. My hope is that we can all be open-minded and loving and actively create communities and contribute to solutions (rather than standing by passively or critically). There are always ways to connect with those around us. That’s part of the creative impulse.

Do you have any examples of looking actively for solutions in creating community that you’d like to share?

Have you heard anything about Mormon Women for Ethical Government? I’ll mention this briefly, since I think it’s a great example. People both in and out of the Church have felt discouraged by the current political climate and, frankly, a little helpless. A few months ago, my mom, a couple friends, and I began discussing ways we could make a difference. When my mom set up a Facebook group as a brainstorming platform, none of us had any idea how quickly our numbers would balloon. I added friends, and those people started adding friends, and within a week and a half, there were over 2,000 members. It was inspiring. We now have chapters in 40 of the 50 states.

And what is the purpose of the group?

It’s a non-partisan group dedicated to peaceful activism. Our mantra is, “We will not be complicit by being complacent.” It’s meant to be a constructive place for solutions, not just a place to air concerns or fling dirt. We have about 5,000 members now, and those 5,000 voices have combined to enact real change. When you have 5,000 people on Facebook who see a notice to call their representative about a certain issue, it does make a difference. I would consider Mormon Women for Ethical Government one of many communities that are actively confronting destructive forces in creative ways. Whether your tool is music or political activism or anything in between, I think the Lord can use those gifts to create communities and influence the world for the better.

At A Glance

Name: Erica Glenn

Age: 31

Location: Mesa, Arizona

Marital History: Single

Occupation: Director of Performing Arts at the American International School of Utah; Doctoral Teaching Assistant at Arizona State University; Freelance Composer and Playwright

Schools Attended: Arizona State University, Longy Conservatory, Harvard

Languages Spoken at Home: English, occasionally Russian

Favorite Hymn: “Abide with Me”

Website: www.ericakyreeglenn.com

Interview Produced by Megan Armknecht