As a psychotherapist practicing in Chicago, Jennifer understands how important sexual intimacy can be to healthy, honest marriages. Jennifer professionally helps LDS women find ways to overcome cultural and psychological barriers to sexual desire, and shares some of her wisdom in this interview.

You wrote your dissertation on LDS women and sexuality and have given presentations on making marriages more passionate. How did you become interested in this?

I began my studies at BYU in 1985. At the time, I wasn’t very educationally driven. Honestly, my bigger goal was to get married, but because I had to pay for my own education, I recognized it would serve me well to get scholarships, so I became more of an academic and really enjoyed it. It shifted my vision of who I could be. I was initially interested in design and architecture, but when I returned from my mission to southern Spain, I decided I wanted to be a therapist. I graduated with degrees in psychology and women’s studies. I also returned to BYU in the midst of the turmoil happening in the early 90s when Tomi-Ann Roberts, a non-Mormon psychology professor, and English professor Cecilia Konchar Farr taught there. I was fortunate to be at BYU during that time, grappling with questions about women’s status in the church and how it related to my own experience and anxiety and grief about who I believed I was supposed to be as an LDS woman. It was very helpful for me to be exposed to feminist ideas and thinking; I’m very grateful to have been there during that time.

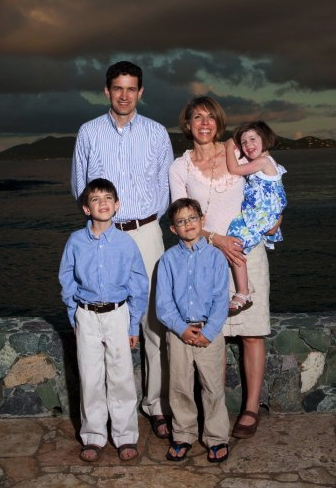

I went on to get my master’s and PhD in counseling psychology from Boston College. New England was closer to the culture and geography that I was most happy in (I grew up in Vermont). It is also where I met John, to whom I’m now married.

In grad school, I remember someone presenting a case about a woman who, at age 25, was still a virgin for religious reasons. The senior clinician who was giving feedback said that the client was obviously sexually repressed and must have had a lot of anxiety about sex. I remember speaking up and saying I didn’t think that was necessarily the case—her sexual abstinence could be because of her own integrity, a reflection of her own convictions. I was—not surprisingly—the only one with that viewpoint.

I grappled with how feminism often mischaracterizes conservative religious women’s choices. Most feminist theories see religious women’s choices as a result of fear and limited exposure, and not necessarily a result of genuine conviction and empowered choice. Yet at that time in my life, I saw many smart, strong, capable LDS women who were choosing to be active members of the church, women who wanted the good things that the church offered.

During my graduate studies, and in part because I was asked to teach an undergraduate course on human sexuality, I became more reflective about the sexually conservative environment I had grown up in. I saw that our perspective on sexuality gave it deeper meaning than I thought the larger culture did, and I was grateful for that. At the same time, I saw LDS friends getting married who had a lot of unhappiness in their sexual relationships. There is a lot of cultural anxiety about sex among our membership, and I had inherited some of that as well, so it made me interested in what Mormon women’s experiences are with sexuality and how they compare to non-LDS women’s experiences, as well as if they fit with the feminist perspectives I was familiar with. So I decided to write my dissertation on LDS women and sexuality.

How has your faith helped you in your profession?

While I was in my PhD program, I was told that I took the pursuit of truth very seriously in comparison to other students—I think that was a reflection of being a Mormon. Discovering what is true really matters, and I think that’s been an important part of my own evolution as a thinker. I deeply value the reference point the church has given me as I’ve explored other ideas and viewpoints. The church’s positions have enriched who I am, particularly around being a mother.

What are some of your core beliefs about sexuality?

First, I think sexuality is God-given and fundamental to our human experience. It’s not peripheral. Our sexuality is fundamental to our spiritual and moral development. Our theology, more than any other Christian faith, teaches us that the body is fundamental to our spiritual development; we were given a body to become more like God, with all of the parts and passions of our heavenly parents.

Second, I think a healthy sexual relationship is fundamental to a good marriage. When sexual relationships aren’t working well, they account for about 65 percent of people’s stated dissatisfaction; when a sexual relationship is working well, it accounts for about 20 percent of people’s satisfaction. In other words, sex has a more powerful negative effect than positive effect. When it’s working well, it really enhances and makes people happy to be in their marriage. When it’s not working well, it deeply undermines a marriage relationship. Of course, it’s not the most important part of a marriage, but it supports a happy, healthy marriage.

What would you say are the most common cultural or psychological barriers for healthy sexual relationships?

For Mormon women, and I’m speaking in general terms, I see a deep disownership of their sexuality. In other words, they often say to themselves: “This isn’t really my domain. My way of relating to sex is accommodating my spouse’s desire.” Often, when women first get married, they might be a little excited and curious and interested, but when they transition into marriage, it quickly becomes about duty and obligation, another job, someone else to care of; it isn’t passionate or desirable, and then they feel guilty about that.

I think part of that disowernship comes from a sexual double standard that tends to bleed into our theology. While we expect both men and women to be chaste until marriage, it often gets communicated in ways that create different meanings for them. For women, it’s often conveyed that they’re less sexual than men and that because they’re inherently less sexual, they shouldn’t associate sexuality as part of their identity. This is problematic for women because they don’t feel like they should think “I am sexual” or “I have desire.” For many LDS women, the idea of loving sex and embracing their eroticism seems so incongruent with the idealized Mormon woman, and therefore a lot of women have a hard time seeing the possibility of healthy sexual desire in themselves.

Women in my research who were comfortable with themselves as sexual beings rejected this double standard completely. They understood that physical intimacy doesn’t have anything to do with placating a man or earning his approval. It’s about expressing themselves to the one they love and maintaining and respecting their own dignity and desire at the same time. They also saw the law of chastity as being positive and protective for them—that it held men to a higher standard than men in the larger culture, and this provided them with what they wanted: committed sexuality, domesticated sexuality with men who were willing to commit to them and create a family with them.

Also, many of the women I meet often have a spouse who thinks they’re attractive, but the wife has a hard time feeling sexual when she doesn’t fit an externalized standard of beauty. Part of the work I do is helping women embrace themselves—to stop living for everyone else, to develop deeper self-acceptance. When people say they want intimacy, they imply that they want to be validated and to hear that their partner approves of everything about them. But true intimacy is a willingness to bring your very flawed self to somebody else, to be fully seen by that person, and to embrace yourself enough to let your flawed self be known. I think that truly letting ourselves be known to another person is something both men and women need to learn in order to have positive, intimate relationships.

So how do you suggest women overcome those cultural and psychological barriers?

I don’t know why, as a church, we need to be invested in telling women who they ought to be, because if we are so naturally those things, then let us just be what we naturally are. Let women define themselves, because as soon as you tell a woman that she is inherently nurturing and giving and happily goes without, it tells her that wanting and desire and self-care are somehow not feminine and therefore not okay. Yet I think those qualities are inherent to good sexuality.

One example of this is found in the Young Men and Young Women lesson manuals. One of the chapters in Aaronic Priesthood Manual 3 is “Choosing an Eternal Companion” and the Young Women’s corollary lesson is “Preparing to Become an Eternal Companion.” It’s indicative of the way we talk about men and women—men are agentic, making choices, deciding what they want, while women are passive, preparing to be chosen, trying to be wanted, supportive of male roles, etc. That kind of language and ideology doesn’t prepare someone to have pleasure and desire in sex and life. It preps them to feel needless and wantless and depressed. To be clear, I don’t think it has anything to do with the gospel. I don’t. It’s a cultural thing. I believe there are natural differences between men and women, but we would do much better if we would express our uniqueness to one another rather than trying to live up to cultural dictates of who we are supposed to be.

One way to reverse this is to talk about what you want in your relationships, and what you want in life in general. Define who you want to be, what you want your relationship with God to be, and then be true to those desires as they relate to your sexuality and to men in your life. I think it’s a much more powerful way to motivate young women to obey the law of chastity and other gospel principles. She’s doing it because she wants the positive benefits of living by it, and she expects the men she’s with to live by it, too. Knowing what you desire gives you the courage to go after the things that matter to you. It’s the best antidote to depression.

In one of your presentations you mentioned that sex is like learning a new language. How so?

If you’re trying to learn German, you’ll learn it a lot better if you truly want to learn how to converse in it. You bring a different energy to the process. So, desire is the first step. I don’t mean physiological desire. It’s truly wanting to want. Often in my work, I’m first helping people discover why they don’t want to even want sex. A lot of women don’t want to be sexual because they feel like they will be taken over by their spouse’s desires, or sex will be a way of condoning their husband’s bad behavior in their relationship. For these women, not wanting sex is their way to hold on to their sense of self or rebel against the pressures in the relationship. An important piece is learning how to hold on to your sense of self while expressing yourself to your spouse. For many people, as soon as they are intimately connected, and I mean even in an embrace with their spouse, they begin to feel anxious and start thinking about who they’re suppose to be or who they don’t want to be with respect to their spouse. Learning to be intimate is about calming yourself enough to actually be present and more genuine in those interactions.

I often have couples engage in physical interactions lower than intercourse, like hugging one another, and track what’s going on in their minds. This can expose what’s undermining the sexual relationship. One client’s throat literally closes up when she hugs her spouse because she thinks about all of the things she needs to be in order to please him. I help women learn how to calm themselves and understand that intimate interactions won’t work out of a sense of duty or obligation. Instead, you often need to learn how to be truer to yourself while you’re with your spouse in order to find more genuine pleasure. Being less reactive and more emotionally grounded becomes the emotional framework of all emotional and physical interactions. Otherwise, you’re just trying to be who someone else wants you to be, and interactions end up being stilted or uncomfortable, which eventually undermines intimacy and desire.

Any final advice you’d like to share?

It’s way too cliché, but be yourself. Don’t disown your strengths, and certainly don’t disown them and call it being Christ-like—that drives me crazy when we throw ourselves under the bus and then say it’s Christ-like. Women have tremendous capacity, creativity, ability and wisdom that’s needed in order for ourselves, our communities and our families to thrive. Don’t devalue your strengths and desires. Keep evolving.

At A Glance

Jennifer Finlayson-Fife

Location: Chicago, IL

Location: Chicago, IL

Age: 44

Marital status: Married

Occupation: Professional Counselor

Children: Graham (13), Elliot (10), Jane (6)

Schools Attended: Brigham Young University, Boston College

Languages Spoken at Home: English

Favorite Hymn: “Come, Thou Fount of Every Blessing”

On The Web: www.finlayson-fife.com and www.drjenniferfife.blogspot.com

Interview by Kathryn Peterson. Photos used with permission.

At A Glance