Listen to this interview at the Mormon Women Project podcast, available on all platforms.

Elizabeth Ostler is a theater-maker, activist, and professor living in Brooklyn, New York. She specializes in directing and puppetry, and in coaching others on how to tell their stories. A survivor of childhood abuse and of an abusive marriage, she dedicates her artistic work to advocating for other victims and raising awareness about domestic violence and human trafficking. She has felt the companionship of the Savior throughout her life, and her knowledge of His love and of her inherent value helped her find the courage to walk away from abuse, to work through her trauma, and to shine a light for others. Elizabeth is co-editor of the Mormon Women Project.

Why are you a storyteller, and why do stories matter so much to you?

I’ve really been drawn to stories most of my life. I always loved being told stories, and I have early memories of spending time with my grandmother, my Grandma Laura, reading me Hansel and Gretel, and others she made up. I also have early memories of making up stories with my sisters and my cousins, and some of those would be plays that we would torture our family members by having them watch. It’s always been a way in which I have made sense of the world and made meaning out of the world, and that has continued throughout my life.

I believe that the shortest distance between you and me is a story. I see this in my own life and as a professional storyteller. If there is a distance between us—I don’t understand you, or you’re an other just because you’re unfamiliar, or even if I’m struggling with you—if I know your story, if I can hold enough space to hear your story or even a portion of your story, it changes me. I find this over and over again that even if I struggle with someone, once I hear their story, I at least can have compassion. I think in a world that’s becoming divisive story is an integral part of us finding our way back to each other. We need to have the courage to tell our stories and the courage to hear other people’s stories.

Elizabeth Ostler

As a storyteller, and a director, and an editor, you’ve taken on an activist role on behalf of victims of abuse. Would you like to talk about the experiences in your life that led to this?

This has been a very deliberate choice in my life, to take on this activist role. The causes that I have, I wouldn’t say I sought out. I would say my life experiences and the things that happened to me led them to become my causes. I wouldn’t have chosen to be an advocate around domestic violence or human trafficking and even now prison reform.

Somebody said to me once that you need to leave things better than you found them. I really internalized that, so whenever I come into contact with something, there’s a deep-in-my-soul part of me that wants to leave it better than I found it. There are also a few things I’ve known about myself, since I’ve had any sense of self, and justice in my belly is one of those things. I think I’ve always been an activist, and it’s been my life experiences that have galvanized these particular issues to be the ones I continually write about and create theater about and dialogue about.

Elizabeth specializes in puppetry and visual art, as well as theater directing

You, yourself, have been a victim of abuse and domestic violence. Would you like to share how you journeyed from there to being the very powerful advocate that you are now?

I do think it is a journey, and I appreciate you using that word because there are things that happen to us in our lives that we don’t have control over and profoundly alter us as humans. When we are empowered enough or courageous enough to do the work we need to do to step out of the victim role, we become survivors, and what I’ve learned in my own work is that we can then transition from survivor to activist. And that is a journey.

I grew up in a home that was abusive. There was emotional and psychological abuse within my family that I was growing up in, and then there was sexual abuse from a family member—an uncle—that had a profound effect on my development, on how I valued my worth, and on how I trusted other people. I ended up becoming quite rigid in my thinking and wanting to do everything right, so I wouldn’t get in trouble, as a way to mitigate the abuse I was experiencing.

Once I left my home to go to school, I met my now ex-husband, and his love was familiar. I was drawn to somebody who was also verbally and emotionally abusive. It wasn’t alarming to me when he started treating me that way. Did I like it? No! Did I try and stick up for myself? Sure. But at the end of the day, it was familiar. I was able to justify some of the behavior or explain away some of the behavior that someone who hadn’t been abused in the same ways I had wouldn’t have tolerated nor gotten into a relationship. These things don’t happen in a vacuum; that was a really important lesson for me to learn as I began healing. All of these experiences are connected.

We dated for two years, we were married for six, and then on our sixth wedding anniversary, I moved into my own apartment. It took almost another two years for us to get divorced. During that marriage, I lost me. I often say: to know me now is not to know me then. I became a shell of a person. One of the things about domestic violence is that you’re trauma bonded, and in a trauma bond you become an extension of your abuser. That was very much true for me. I didn’t have an identity outside of his wants and expectations for me, and I actively tried to squash my own identity and sense of being in order to maintain the relationship, in order to secure what I thought was love, in order to honor the vows we had made together, because I really, genuinely believed that without him I would be nothing. So, I sacrificed myself in order to be connected to him.

Elizabeth Ostler

How did you find the wisdom and the power to leave?

When I look back at that time, in some ways it feels like a book I once read, or a movie I once saw. There’s so much darkness around it. But when I really think back and meditate into it, there were moments of light.

Here’s the thing: I didn’t know I was being abused because it was so familiar to me. When we separated, I went to a therapist, because I couldn’t break the trauma bond. I couldn’t stop seeing him even though I wanted to stop seeing him. The therapist said to me, “You realize you’re in an abusive relationship, right?” I was like, “No, I’m not.” And she just looked at me as if to say, “There’s so much work for us to do.” The first thing she had me do was read this book, The Verbally Abusive Relationship, and within the first ten pages there’s a checklist of twenty questions about your relationship. At the end it says, “If you answered yes to five of them, you may be in an abusive relationship,” and I had answered yes to all but one.

I had to be taught that the way I was being treated wasn’t normal, and that I didn’t deserve it. Therapy was a huge part of that; creating art helped me find my identity again; friends and family members were a huge, huge part of that. When I was in the strong pull of that relationship, I was completely isolated. It got so bad that I wasn’t speaking to my parents, which is very normal in a domestic violence relationship. When we separated, I started slowly reaching back out to my parents. At that time, I didn’t trust any of my choices—his words and thoughts and ideology were so in my brain. In fact, domestic violence is on the Stockholm Syndrome scale: you become conditioned to think the way they think. That was part of my work in getting healthy. I had to unhinge my brain from his and identify my own voice. It was really scary and really hard, so I didn’t trust any choices that I wanted to make. My mom said to me once when I was talking to her about this, “Identify the two or three people that you really trust and that you know want the best for you, and only listen to them.” That’s literally what I did. I had two girlfriends and my mom, and whenever I had to make any significant decisions, I just went to them and asked, “What do I do?” And then I just did what they told me to do until I was strong enough, and got enough clarity, and enough distance from him, and enough healing that I could start to think for myself. That probably took me about eighteen months before I could really start hearing my own voice and trusting it.

Elizabeth Ostler

I’m curious about the role that the church played in all of this for you, and the gospel, because you grew up in a member family.

My family was in and out of activity all of my growing up. That was at times hard for me, because I was born with a believing spirit. One of my gifts of the spirit is that I, very early on, gained a testimony that Jesus was the Christ. I can remember at age five having an experience and knowing Jesus was the Christ, and that has never wavered in the decades since. That has been a real gift, even a life-saving gift for me because it has helped me be rooted. All these things happened to me that made me question my value, but knowing that Jesus was the Christ and believing in a loving Heavenly Father helped comfort me during really hard times.

Even though my parents and family were in and out of activity, I always wanted to be active, and there were times when I was the only active member. That was a real positive thing for me. I longed for the typical Mormon family—that all went to church together, that had Family Home Evening, that had family prayer study and scripture study. I longed for that, but at the same time, my mom was always willing to have really deep spiritual conversations with me at any age. My mom has been pretty active most of her life. One of the things I love about her is that she is so curious, and she taught me how to be curious. So while the gospel was a real touchstone and a real foundation for me, I still was able to have some critical thinking around it that helped me develop a testimony on my own. I didn’t have a family to lean on, my parents’ testimony to hold onto, or anyone else’s. I really had to develop my own. Believing that God knew me and that Jesus was the Christ was really helpful for me as I navigated being abused as a child and then in my marriage.

So even when you felt like you had lost Liz, you didn’t feel like you lost Jesus?

Exactly. Very much. Even when I was married, I had started to work through some of my childhood trauma, and I had some real choice moments of feeling Christ heal parts of that. I went to him in prayer and asked for help through the Atonement, and remembered that image of Christ in 3 Nephi asking for the little children to be brought to him. I knew that those children were suffering like I was, and that he could do the same for me that he did for them.

That’s so beautiful. He says to bring the children to him, and you brought your child self—your memories and your childhood trauma—to him for healing.

And I still do to this day, because this is, for me, a lifelong process as I continue to heal and work through things. Here’s the thing when you’ve experience trauma, particularly childhood trauma: it does impact the rest of your life. There isn’t a magic bullet. There isn’t just the one moment and it is forever fixed. What you learn are tools to do things better, and you learn how to let go of a lot of the pain, but that doesn’t mean you don’t get triggered, and that doesn’t mean that the obstacles don’t still manifest—you just have a better way of handling them. This is still one of my tools: when things get kicked up, when I find a younger part of me that I am aware is still hurting, I take that part of me back and use the Atonement.

Elizabeth Ostler

Were there any moments in particular that you felt the love of God, or that you felt empowered to reclaim yourself?

Yes. Of course there were small moments throughout, but I think of two in particular. At the end of the relationship I was so miserable and I was so lonely, and I caught my ex-husband in a lie. But I didn’t want to have caught him because I was living in a house of cards, and if it was a lie, then it would all come tumbling down. And I wasn’t prepared for that. I remember praying really fervently to believe this lie. I said, “Make this lie a truth.” And I was left hollow. It was one of those moments where I felt a real absence of the spirit, and it was so clear to me that this wasn’t of God, and that there wasn’t any way that He was going to say it was okay. Not even to give me comfort. There was a “No.” That really helped wake me up in a way. I view that as an act of love, as a way of helping me. What would happen previously is that I would seek comfort and I would get comfort, and then I would stay. In this case, I didn’t get any comfort. I got a hollow feeling, and I knew I had to make choices.

Then the last time I had contact with my ex-husband led to a real scary moment. I was living in my own place, and he tried to break into my apartment while I was in it. It was terrifying, and the police were called, and he was arrested. It was a rare moment of me standing against him and telling him no. I was living in Salt Lake City at the time, and I went to the courthouse to file a protective order. I didn’t know the resources that were available to me as a victim of domestic violence! There are so many resources available, and it was so—I don’t even know the words. To be able to walk into that courthouse terrified, not knowing what to do, shaking with my police report in my hands—and then a group of people, who were trained to do this, just took care of everything for me. Somebody stayed with me the whole time, and they gave me a victim’s advocate. That allowed me to become empowered. It was a real gift. It was such a transformative moment.

The process takes all day, and there was a moment when I was sitting in the waiting room, really overcome with gratitude that these resources were there for me when I was ready for help. I remember thinking, How is this possible? How does this exist? I realized in that moment that these things existed because other women before me had been either killed or maimed—that their advocacy work had led to this. I felt a deep kindred sisterhood with them, and in that moment, I made a vow to them that from that moment on, I would use my voice to bring awareness to domestic violence, that I wasn’t going to be quiet and I wasn’t going to be still any longer. This was my way of showing gratitude to them. It really was a vow that I made with them, and in that moment it felt sanctified. I felt the Spirit so strongly in that vow that it has been very much at the core of my advocacy work. At times when I get frustrated or tired, I remember that vow, and I remember what those women did so that I could have that resource, and it fuels me to continue to do this work.

How have you used your art and theater in your advocacy work and in your own healing process? What other means have you used to be an advocate?

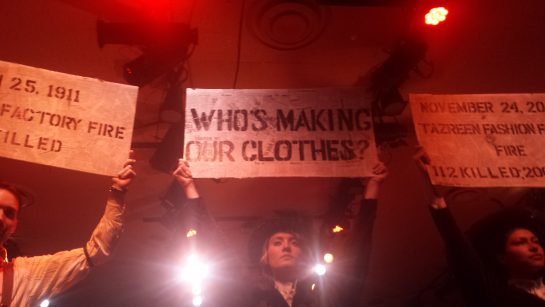

I was a master at denial in order to stay in the relationship. Willfully in denial. So a lot of my work is about bringing awareness, it’s about helping people who are currently in abusive situations to realize: Oh, when I’m treated like this that’s not normal, or this is actually not my fault. And also to bring awareness to people who are close to someone in an abusive relationship. To help them have more compassion and know what to do. I do it by creating theater pieces that I devise myself—meaning that I write or create with an ensemble—or by directing shows that already exist. I’ve directed a beautiful play by Victoria Nalani Kneubuhl called The Story of Susannah that’s about women in a domestic violence safe house. I’ve directed The Vagina Monologues, and The Triangle Factory Fire. (That one was to bring more awareness to labor trafficking in the clothing industry, because today there are more people enslaved than ever before in recorded history. It’s an $86 billion industry, and this horrifies me.)

Elizabeth’s production of The Triangle Factory Fire

I’m also a visual artist. Whenever I get really triggered or angry about a social cause or a situation, I often think in terms of visual art in order to work out my emotions. I’ve created a penny sculpture; it’s a female bodice to which I’ve wired pennies that I call “Victimless Crime,” and it’s a commentary on the way we treat prostituted human beings. I think we throw them away like we do pennies. The vast majority of the pennies on the sculpture were pulled from the street as I was going about my life and my friends were going about their lives. I want people to have an awareness and start having a conversation about these things. We can’t be in denial.

Elizabeth’s piece, “Victimless Crime”

Has it been hard for you to stay in that story so much? When you’re directing these pieces or creating this art, as someone who has been a victim, is it hard for you to be there in that space? How do you continue to heal through that?

That’s such a great question. At times it can be exhausting, but it’s not hard. I have done enough mental health work and spiritual work around these issues that it’s not re-traumatizing to go back in. It continues to heal my wounds because it further empowers me. It helps me understand it from different points of view and, yes, I travel into that darkness, but I bring light with me. I’m shining light into the darkness. I don’t feel when I leave it that the darkness has diminished my light; I feel like I’m even brighter for having done it. I think that’s part of the gift of doing the hard work of healing. One of my favorite quotes ever—it maybe needs to be on my headstone, if I have a headstone—is by a trauma specialist named Peter Levine. He said, “Unprocessed trauma is a living hell. Processed trauma is a gift of the gods.” Capital T truth. It’s a gift of the gods. Processing my trauma has helped me get closer to my divine self, and part of that divine self is the ability to stand in dark places and shine light.

Elizabeth Ostler

There’s been a lot of talk recently in the church about sexual abuse and ecclesiastical roles. What kind of support did you receive or wish you’d received from your local church leaders through all of this?

Particularly around my own sexual abuse, I never told an ecclesiastical leader. I was never a child or an adolescent who told. It was a deep, dark secret that didn’t break in my family until I was a young adult. But when I was getting divorced, I went to my Bishop in my family ward who I really admired and liked and trusted, and he was one of the first people that I told about the things that were happening. I was too scared to say divorce. I knew in my heart I wanted to get divorced, but I was too scared to say it to him in particular, a spiritual leader. I wasn’t married in the temple—we were married civilly, so I didn’t have to deal with any of that. But I remember telling him what happened, and he just listened and was so kind and supportive, and then he said, “Well, what are you going to do?” And I wanted to say, “Get divorced,” but I couldn’t. I was too afraid, and that word felt too big for me, so I said, “I don’t know.” He looked at me, and he said, “You do know what you need to do, you just need the courage to do it.” And I said, “I think I have to move and be released from my calling.” I was a Relief Society teacher, which is the best calling in the church, hands down my favorite calling. And he said, “You’re going to be going through a lot of changes in your life, and you need to be somewhere where people know you and love you, and so I’m not releasing you from your calling. You can live wherever, but you’re still one of our Relief Society teachers.” That was such a gift, because he was exactly right. That was really a choice moment for me because I felt supported.

This was during that time when I couldn’t trust my own thoughts, so it was very valuable to have somebody say: It’s really about courage here, and you’ll find it. Which reminds me of something my mom had said to me another time. A couple of years before I separated, my ex and I got into a particularly nasty moment, and I went to my mom’s house to get away from him for the rest of the day. It was one of the few times that I admitted to my family anything that was happening. They were acutely aware of the situation but didn’t know how to approach me, because I’d get super defensive. It was one of the rare times when I went to my mom and said, “This isn’t working and I’m in pain.” And she said to me, “What’s the worst thing that could happen to you in this?” And I said, “Getting divorced.” And she said, “No. Losing yourself.”

As I was trying to find my own self, these little seeds were getting planted—by my mom, by my bishop, by my therapist—until I could get the courage I needed to really sever it and take ownership of my own life.

Elizabeth recently served as Young Women president in her ward

What advice would you give to somebody who has a friend or loved one they perceive to be in an abusive relationship?

It’s about being a place of comfort and a place of listening, and not to try to fix it. This is the hardest part of it, because you can’t force somebody out of a relationship that they’re not ready to leave, even though you can see it destroying them, even when you can see that their life is being threatened. There’s this language: “Why doesn’t she just leave?” Because she can’t. For so many reasons. If you do try to yank them out of the relationship, you will be cut off. And then you have no influence. Tell them that they’re loved and walk with them as best you can. Be there, and be a resource so that when they are ready, you are someone who’s safe for them to reach out to because you have proved that you will walk with them. And any moment you can, tell them, “This is not your fault,” and “You don’t deserve this.” That is really powerful language.

The other thing to do is to take notes because the person is in it, they’re living through it, but as an outsider, you can say, “On this day, this happened. On this day, bruises here.” Because later, and hopefully there will be a time that they do leave, your record will help them get the legal support that they need.

Walk with them, and keep a record.

I’m going to steal another moment and speak to anyone who, in reading this, might be able to identify with me in some place—and say to them that this isn’t your fault. Nobody deserves to be treated without dignity. We are all entitled to love, and we are all entitled to dignity, and we are all entitled to peace, and we are all entitled to live as our best selves. Now that doesn’t mean that it’s not hard, and there aren’t struggles, but that’s different when you’re being abused. There’s a big difference between regular life struggles and when you’re being abused. There are so many resources available. There are so many resources available! Just have the courage to reach out to them.

You tell your story so well, and I know that your job in life right now is to bring out other people’s stories. But that’s a process—learning how to do it. Were you always so good at this? How do we learn, and why should we?

Those are great questions! I would say there was an innate part of me that was drawn to it. I absolutely had to learn what makes for a compelling story: beginnings, middles, and ends. There are so many books out there and TED talks and resources of how to be a good storyteller. To do a little bit of a plug, I hold workshops on how to tell yours story through my company, Life’s Echoes. I’m not the only one who does this. There are other people that can teach you how to tell your story.

Elizabeth Ostler

I would say if this is important to you, the place to start is to choose to live an authentic life. Find out what your voice is, because here’s the remarkable thing: No one is going to have the same mortal experience that you have had. No one. No one will have the same experiences and understandings and see things the way that you have. So yes, there are thousands and millions of stories out there, but there’s not your story. I think this is the other thing people get daunted by, where they say, “Why do I need to tell my story? This story already exists!” But yours doesn’t. Your story doesn’t exist. You’re the only one that can tell your story. And if you don’t tell your story, it is lost. There’s this beautiful quote by Alex Haley, “Every death is like the burning of a library.” It’s so true! If you don’t tell your story, it never gets told. And we need it. We need to hear each other’s’ stories, so that we can build strong communities and build kinship and belonging. That is an integral part of being disciples of Christ, of building up Zion, and one of our tools is telling our stories. Just start. You may or may not get it right or wrong at the beginning, but you just have to start, and the more you tell the story, the more you’ll learn. Start telling it with your voice, start writing it down, journaling, whatever, but start recording your story, because we need them. We need everybody’s story.

At A Glance

Name: Elizabeth Ostler

Age: 41

Location: Brooklyn, New York

Marital History: Divorced

Occupation: Theater-Maker, Storyteller-in-Chief at Life's Echoes, and Adjunct Professor

Convert to the Church?: Technically no, but spiritually yes

Schools Attended: Sarah Lawrence College (BA), and Brooklyn College (MFA)

Favorite Hymn: "I Stand All Amazed" and "As Sisters in Zion"

Personal Website: http://elizabethostler.com/

Business Website: http://lifesechoes.com/

Interview Produced by Meredith Marshall Nelson