Gospel Doctrine Old Testament Lesson #18, Joshua 1; Joshua 3–4; 6; Joshua 23; 24:14–31.

You cannot tell the story of Jericho, critical to Joshua’s prophetic narrative, without a woman—Rahab[1]. I particularly like this story because it complicates our assumptions and judgments of others and remind us that though women may be a minority in scripture they always enter the narrative at critical junctures. Rahab was considered a “Woman of Valor” in Jewish Midrashim. Her name means “to be wide or enlarge”—perhaps a shortened version of “God has enlarged.” The children of Israel could not have entered the promised land without her. Her story reminds us that God is no respecter of persons, that God’s grace can transform all of us, and that no matter our past we can extend the same salvation we have received to others and help lead them to the promised land. We can all become “saviours on Mt. Zion” (Obad. 1:21).

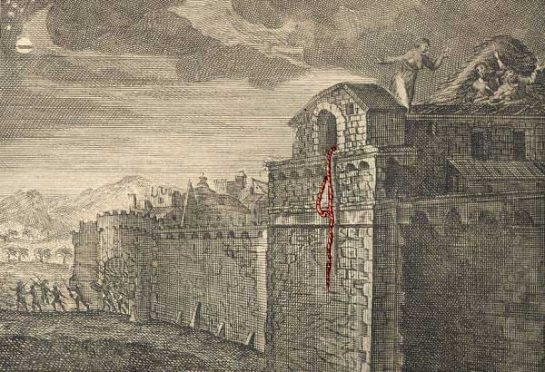

Rahab lived on the margins of Jericho’s society and Jericho itself. The city boasted of two walls of protection and her house was attached to the most outside wall of the city. Her flat roof provided storage for flax (which she might have spun into that salvific scarlet rope) as well as a convenient hiding place for spies. Be sure not to miss the comedic elements of the narrative—the hero of the story is not actually a hero at all by Israelite cultural ideals. A woman could never be the hero. Yet our antihero is not only a woman, but a Canaanite, an owner of her own public house, and a member of the “world’s most ancient profession”—a harlot or prostitute. Some have tried to say she was not a prostitute at all, but the Hebrew zonah used here consistently denotes illicit sexual relations. I come from a long line of women who have done what they needed to do to care for their families—this did not mean that they were always right or exempt from the judgment of others. Discomfort is essential to the narrative.

As the new-minted leader of Israel, Joshua sent spies to assess their position as Moses had done with him—however, these spies sent to Jericho were not nearly as effective as Joshua and Caleb. They arrive in Jericho and enter into Rahab’s public house. The narrative is immediately subverted as the bungling spies are found out within two verses. The King’s Guard knows exactly where they are and confront Rahab. Countering our own assumptions about such a woman, she misdirects king’s guard and sends them far away.

After surprising us, she finds the “spies” on the roof and stuns us again as she offers her powerful and prophetic witness of Jehovah:

I know that the LORD hath given you the land,

and that your terror is fallen upon us,

and that all the inhabitants of the land faint because of you.

For we have heard how the LORD dried up the water of the Red sea for you,

when ye came out of Egypt;

and what ye did unto the two kings of the Amorites,

that were on the other side Jordan, Sihon and Og,

whom ye utterly destroyed.

And as soon as we had heard these things,

our hearts did melt,

neither did there remain any more courage in any man, because of you:

for the LORD your God, he is God in heaven above, and in earth beneath (Joshua 2:9-11).

She prophesies that the Israelites will be successful. When the spies later report, they quote her witness to Joshua.

She then asks for a “true token” from the spies—a sign of loyalty. The woman from who we don’t expect loyalty offered it and now is vulnerable. She who has protected and cared for her family as well as these strangers now asks the strangers to offer her and all who she protects the same—to “deliver our lives from death” (Joshua 2:12). After they made an oath with her, she let her scarlet rope over the city wall to bring freedom to these models of spycraft ineptitude.

Her scarlet rope offered salvation and, despite their idiocy, the bumbling spies were reciprocally given an opportunity to participate in the salvific work. They too could transform into saviours on Mt. Zion.

As well as a signal to the sufficiency of the grace of God for all, Rahab also serves as a type for Christ in the narrative. This woman on the edge of society—figuratively and literally—offered salvation. The discomfort with our antihero highlights the enlarging and expansive theme of salvation. Salvation comes from the unexpected—from one with “no form nor comeliness.” Yet Christ saves all who come unto him no matter if they be guilty of serious sin or just bumbling idiots. As a believer in the God of Israel, Rahab could accept the salvific offering on her own behalf and then share salvation with others as a saviour on Mt. Zion. Her discipleship comes full circle as she trusts in the loyalty of the spies and offers them the opportunity to likewise join in the work of salvation and save her family. The scarlet rope signaled the encompassing salvation offered, accepted, and shared.

[1] There are at least 2 different Rahabs in scripture—one is deified sea-monster purveyor of chaos in Jewish folklore closely connected to Babylonian creation narratives (Isaiah 27:1, 51:9—2 Nephi 8:9, and Psalm 89:10) and the other is a Canaanite woman who saves the Israelite spies (Joshua 2, Heb 11:31, James 2:25)—here we are concerned with the latter. In reference to the former, Rahab is also used as a pejorative for Egypt.