On April 6, 1994, the airplane carrying the Presidents of Rwanda and Burundi was shot down over Kigali. That moment was like “oil on fire,” setting off the devastating Rwandan Genocide. Yvonne Baraketse’s father, Chief of Staff of the Rwandan army, was also on the airplane and killed in the attack. Yvonne was 14 years old. Her immediate family lost many relatives and friends in the violent aftermath, managing themselves to escape to Belgium. Although prayer had sustained her through the terrors of war, now a refugee she ceased to pray, feeling God had abandoned her and her people. But while in Brussels, she found the Restored Gospel of Jesus Christ, which enabled her to forgive and look forward. She subsequently was made a refugee a second time in Hurricane Katrina, and was inspired to seek an MPA after observing relief efforts there. Yvonne lives in gratitude for her life, and has dedicated it to building bridges and lifting others: through service, through education, through dance. Listen to this interview on the Mormon Women Project Podcast here, or on iTunes or Stitcher.

I understand that you recently traveled to Belgium to visit your family and to remember the experiences you had together in Rwanda. What was that gathering was like?

Oh the gathering was very important and very beautiful. When we fled from Rwanda in 1994 we went to Belgium. I was there all my teenage years and I did my bachelor’s degree there, so that’s really what we called home for a long time. That’s where I met my husband, and that’s where I converted to the Church. My mom has been living there ever since, and it was the logical place to go and remember those 25 years since our dad was assassinated. It was really emotionally charged and at the same time, I’m very grateful that we were able to do that gathering.

Sometimes I look at my family and I’m like, “Who are we to have been saved through that tragedy?” There are so many people who died in that war and genocide, so for us, being able to get together those 25 years later was first of all a moment of gratitude to Heavenly Father. It was also a moment of remembrance of dad and his legacy. The Mass was full of people who were there to support us. You know the whole war in Rwanda was about ethnic groups that were killing each other—the Tutsis and Hutus—but everyone was there regardless of their ethnic group, because there was a need to have a moment to remember those dignitaries who died during that time.

It also was just a moment to remember all the Rwandan people. In fact, during the Mass I was asked to pray, and I prayed for peace for all Rwandans who died in the tragedy. For me, it was also a moment of healing, a moment of forgiveness, a moment of really passing on that message that it’s important to forgive in order to have a peaceful life the way that the Savior taught us. So yes, I did it as a Mormon in the Catholic church and I really felt the Spirit and it was really powerful.

There’s one other experience I want to share about what happened that day. We went to the Mass, and then the Mass ended, and then we went together in private with our close family and friends, and I was also able to pray for my father on behalf of the family. Something really strange happened. The Spirit prompted me to gather everybody to sit together around my father’s big portrait, including the kids because my dad loved kids so much. I felt the Spirit prompt me to call all the kids who were playing outside to come and sit next to the portrait, and that took about twenty minutes. By the time everyone had settled down by the portrait to pray, it was the exact minute and hour that my dad was killed. And that wasn’t planned! To me, that was really a sign that he’s at peace and he was happy, and his spirit was there with us.

When that prayer happened the exact moment he died, to me it was a big testimony that we can do so much for our deceased ones. Commemorating them is part of it, praying for them is part of it, temple work is part of it.

Yvonne with all of her siblings: Maurice, Denise, Fabrice, Josiane, and Alice.

Can you tell me a little bit about your father? What was his legacy?

My dad was a people person. He loved people. He was humble. By the time he died, he held a high rank in the country as the Chief of Staff of the military. He used to take us to visit places where he lived when he was a kid—in the villages where he’d walk miles without shoes on. He’d take us there and hug people and laugh with them and there would be people who would have almost no clothes who were really poor. At that time we were kind of a privileged family living in the city. He would take us every weekend to go back to those roots.

He was a very faithful person too. He used to take us to pray almost every day at the Mass. He was a hard worker. He was a public servant. His career and his life were devoted to his country, to the extent of dying the day he came back from signing the treaties of peace with the president of Rwanda. He was a very strong man. Very charismatic too, obviously, a leader.

He loved people, that’s for sure. Regardless of where they were from, regardless of their ethnic group. My dad was a Hutu in the government, but he wasn’t extremist. He loved everybody. We had friends at home who were Tutsis, who would come to our home. That is a legacy I take with me. Even after the war I remember seeing some of my friends who were Tutsis, and obviously both of us will have lost our loved ones, right? On my dad’s side, almost everybody was killed in his village. Some friends who are Tutsis lost a lot of their loved ones, so we have been able to find ways to sympathize.

When I was in school in Rwanda in primary school, I went to school with Tutsis and Hutus and Twa (Twa is the third ethnic group whom we never mention much). When we were growing up in Rwanda, racism wasn’t as obvious, you know what I’m saying? At least for us kids in schools, and at home too. My dad never taught us, “Oh, you should hate Tutsis,” or “You should hate Twas,” or “You should hate Hutus who are from this region.” I’m really, really grateful for that because I know a lot of people in Rwanda who were taught that they have to hate somebody different.

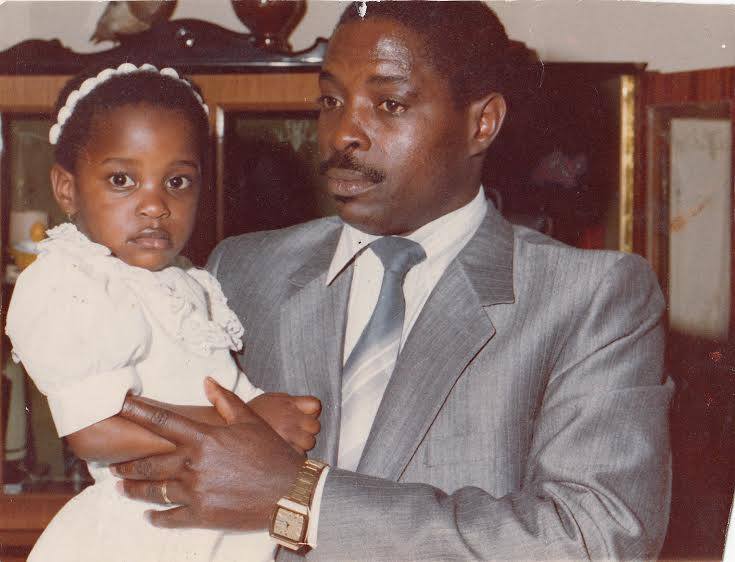

Yvonne, 3 years old, with her father.

How old were you when your family left Rwanda?

I was almost thirteen. At that time, my two older siblings were in Europe because they were in college. There were six of us.

You were raised in a tradition of faith. When you had to flee Rwanda—and I know that’s not the only time that you’ve been made a refugee—what role has your faith played in those moments of dislocation?

It played a very important role even throughout the war. Let’s actually back up. The war in Rwanda started in 1990—people don’t mention that as much—and I was nine. I remember clearly the moment it started, and the fear that I had in me, seeing the shooting going on in the hills. Dad wasn’t there, he had to go and do his duty of defending the country because he was in the military at that time. It was a very fearful moment, and for me, faith is what sustained me throughout all those moments. I remember starting a prayer when I saw the shooting, pleading, “Please Heavenly Father, I don’t want to die. I want to stay alive.” I wanted to do a lot of things in my life. “Please, please, please!” And because I was Catholic I recited the Lord’s Prayer.

Then on April 6, 1994 the airplane of the president was shot down, and my dad was in it. Everybody was so scared because the moment they got shot down, there was this huge noise that everybody heard if you lived in the city, in the capital Kigali. I remember praying again, “Please Heavenly Father, let us leave. I don’t want to die.” I prayed for my family to be safe, and of course at that moment we didn’t know if our dad was still alive or not. There were so many phone calls and we had a lot of confusion. There were two airplanes… he’s not in that one… until the moment we found out that he really died.

I remember again praying so much, because we were so scared. Nobody knew how we were going to get out of there. The war had been going on and you had all these groups that were already in the country. The rebellious army who started the war, that we knew had attacked the country, was already inside, and we were like, “What is going to happen to us?” Because we had heard stories on how they killed people, how they cut women in half, and all this crazy stuff for a little teenager, right? Prayer was what sustained us from that moment, of course.

Yvonne, 11 years old, on their last family vacation at Akagera Park in Rwanda. She remembers these as days of happiness and innocence before the war and her father’s death.

That moment that the airplane was shot down containing the president and my father and a lot of prominent people—that was like fire, that was like oil on fire. That’s really what started the whole killing. Neighbors started killing neighbors, there was no control. I remember praying so hard, constantly, until I would fall asleep. After that, we had to go and witness where my dad’s corpse landed, and I remember getting there as well, and praying so much. We had to constantly be praying all the time, all the time, all the time. Just really as to not fill our spirit or mind with negative thoughts, because at that moment, it wasn’t only the sounds of the war that were happening, but the smell of all those people who were dead. So you couldn’t even hide from it.

We stayed in Kigali from the moment the airplane got shot down April 6, until we were able to get out, I think on the 11th of April. So during those 5 days, I can tell you we were praying all the time. All the time. Because we had no idea how we were going to get out. And to this day, any time when I’m confronted by very, very hard moments in my life, I pray.

When I arrived in Belgium I was completely distressed and traumatized. There was a moment I stopped praying, to be honest with you. I stopped praying because I was angry with Heavenly Father. I would say from age fourteen to maybe sixteen or seventeen, I stopped praying. I was like, “There is no God. There is no God who loves me. Because if there’s a God who loves me, he wouldn’t let me go through this. He wouldn’t take my father that I loved so much. He wouldn’t have let all those people die in vain. He wouldn’t have let the hatred go on to the extent of Tutsis and Hutus killing each other’s families and stuff.” I was so angry I stopped praying, until later when I converted to the Church. Although before I converted to the Church, I tried. I told you I grew up in the Catholic church, and in the Catholic church you do confirmation—the gift of the Holy Ghost you receive in our church—you receive it in the Catholic church later, around seventeen or eighteen. At that moment I tried praying again. But I still couldn’t get any answers to all those questions about why we had to go through all that, until the day I started taking the lessons with our church and I learned about the Plan of Happiness—that it’s part of the test, it’s part of the journey. But that’s not all. There’s a continuity, there’s a way to see our deceased ones—I could go on. The knowledge I got, it’s what really shifted my mindset to be like, “Ok, actually God doesn’t hate me. God didn’t abandon me. It’s me who abandoned him and who didn’t know that there’s a way to return back to him through the Plan of Salvation.”

Yvonne, 14 years old, living in Brussels.

How did you learn about the Church?

My husband and I, we’d known each other for a while when we arrived in Belgium. People in the community who left Rwanda during the wars started mingling and getting to know each other. So we started dating when I was eighteen and we’d known each other for a long time, because he used to come home and help and he was a very nice friend to my mom and family. He also experienced the war, by the way, and he was much older. He was twenty-one when he left Rwanda, and he almost got killed like three times—a machete almost on his head, and a bullet almost going in his head. He saw more things than I did, so when we started dating in 1999, I asked him, “Hey, how come you’re not crazy?” This was during the moment that I was searching, wondering why God doesn’t love me and has abandoned me. We used to have a lot of spiritual conversations; we had philosophy that we liked to read and that he introduced me to. There was a lot of spiritual reading—you know how we say in our church, find knowledge in the best books. Really there were a lot of good books and we’d learn about different religions.

One day I asked him, “Where do you go to church? Because I want to know why you are strong like that—mentally, spiritually—knowing all you’ve been through.” Because me, I was dying inside. From hatred, because of what happened in my family, from questioning why God doesn’t love me, from not forgiving what happened in my family. One day he said, I go to this church, and he just described the area where it was located, and that was it. He didn’t want to tell me which church or anything. Then I just retained all the information he gave me.

One day, by surprise I went there without him knowing that I was coming. That was our church in Brussels that I think has been closed now for the last three years. It was the day of fast and testimony meeting, and boy, I felt the Spirit. I felt something I hadn’t felt for a long time, actually I don’t even think I ever felt. How people would open up and share about the Heavenly Father that is a loving Heavenly Father and how in their own current experience they have that testimony that he exists and a knowledge of his hand. I don’t know who spoke and whatever they said, but something really struck my heart.

But that wasn’t it. It took about two years—I was a stubborn person. I took about two years to have the sister missionaries teach me, and to investigate and read and learn and read the Book of Mormon, all those things. One day I remember reading in the Book of Mormon about those wars happening between the Lamanites and Nephites, and how they’d been fighting and fighting and then they decided to make peace. I could see what was going on in my country. I could see it through the Lamanites and Nephites; I could see the Tutsis and Hutus, that hatred that was going on between them. And I was like, “Oh, so peace is possible through the gospel!”

That’s how the whole negativity I had around what happened in my country and the negativity I had in my heart started to collapse. And then one day, the sister missionaries came to teach me as always, and they opened the hymn and they started singing “I Know That My Redeemer Lives.” Every single word of that hymn just kept opening my heart. I could feel it. It was after that hymn that I decided to convert to the Church, knowing that my Heavenly Father lives, he is a living God. He can be living in my life if I want Him to, if I invite Him in my life. He can wipe away my tears and my fears. Heavenly Father talked to me and reminded me of his love through that hymn and that’s really what shifted my decision to get baptized.

I got baptized on August 11, 2001. Then I had to go through forgiveness, forgiving myself for being really too hard on myself, and also forgiving those who killed my father and my extended family, and really wiping away the hatred and all the darkness that was in me. Just to tell you how hard things were, I had at one time contemplated committing suicide. I’m not the only one. I know a lot of people who have been through that because the trauma of the war was real, but in our community it’s not something we consider very serious. We don’t go to therapists or things like that, and I never did in Belgium either. In our culture, if you do those kinds of things, they consider you crazy. So my only real therapy became the gospel, the answer to all of my problems, and that’s really what shifted my life completely. I became a new person ever since.

Yvonne with her husband and children, 2015, visiting the temple.

What were the tools that you drew from? Were there scriptures that spoke to you? What helped you to cross that bridge of forgiveness?

What really helped me, first of all, was acknowledging that I was a child of God who loves me and who loves all his children the same way. That was the first step, because if you see the other person as a lesser person than you, or unimportant, that means you’re not acknowledging that God loves them. That is the first thing: develop that love for yourself and the love for “thy neighbor.” We need to develop Christ-like love for everyone, anyone who is different from who we are. Because it’s easy actually to hate people because they’re different than you. That’s how racism starts. In Rwanda what was going on was racism, end of story. Racism between two ethnic groups that speak the same language, had almost the same culture—we have about the same customs. It’s not even like in Congo or Ghana where you have two hundred tribes. In my country you only had three tribes that had so much in common, that had been intermarrying a lot.

The other thing I would say is you have to make that effort to get to know them if you don’t know them. Hear their version of things. Because sometimes when there’s a fight going on between two people and the fight keeps going on, it’s because one of the parties is thinking that they’re right and the other one is wrong. No. It’s not true. If we are equal that means we have to accept we both made mistakes and then talk about it and then move on. Unfortunately, in Rwanda we are not at that point yet. There are some efforts that have been happening within the country, but I hope one day I will be able to sit at the same table as somebody from the other side, from the other government, or maybe from the other side who killed my family and be able to shake their hands and say, “Yeah, I really forgive you.” But it starts in the heart, really, even if the physical forgiveness is not happening. It’s really a change of heart. That is where you can find the answers.

A “change of heart” as we say in the Book of Mormon and in our Mormon culture—it’s really deciding you’re changing your heart, you’re turning away from that sin that is just dragging you down, which for me was hatred and darkness and doubt and fear. You can change your heart and rely more on the Savior and have more faith in Him that He loves you and He knows your life, and that His Plan of Salvation is going to guide you in everything you do. He’s a loving father and He wants the best for you. And the way He wants the best for you is the way He wants the best for the other person. So that knowledge really just changes everything. Some people don’t have that knowledge, unfortunately, and we don’t realize that when we have those negative feelings it’s a cycle. You kill their family, and then their kids will come and kill your own kids, and then your kids will kill their own grandkids. That cycle was broken in the Book of Mormon by the Lamanites and the Nephites, and it is the one cycle that needs to be broken everywhere in the world, starting in Rwanda. When people have the knowledge that they have to stop the cycle, somebody’s got to make the sacrifice to stop the cycle of hatred and war. That’s how the whole forgiveness happens. Not everybody wants to go that way.

Yvonne Baraketse, 2016.

I imagine that the change of heart you had, maybe combined with your father’s legacy, are what have been behind your drive to build community and to lift up other refugees in your work. Could you talk about what you’ve been doing the last few years?

About two or three years ago, some other friends and I founded a non-profit called Ngoma Y’Africa Cultural Center with the motive of creating more awareness of people from Africa. I realized when I came to Utah as a student that a lot of people from Africa, when they get here, they get lost, or they want a place where they can go and remember their culture. But also, I will go a step beyond, it’s not only to get together and remember the culture, but it’s also to take that knowledge you have of yourself and put it at the benefit of the community. Because again—remember what I just said—if people don’t know each other, that’s when the hatred starts. People are scared of what they don’t know, or who they don’t know. I have myself been through that in my own country.

It was really what drove me, “You’re here, you’re African, great. You’re proud of who you are, but bring it to the benefit of the Utah community who never got a chance to go to Africa. Or to someone who maybe has been to Africa as a missionary, but they want to learn more.” That’s the reason Ngoma started in the first place. We let anybody come in, not only people from Africa. We have lots of people from America. We have people from Latino countries. We are learning and educating the community, then the biases become insignificant. This is why we keep doing this. Right now we are working on a play, and we’ve done other projects with that mission of educating the community. I’m no longer president of Ngoma now; I decided to give others that opportunity.

As far as working with refugees, I myself have been a refugee. I was able to go volunteer with refugees back in Salt Lake when I was a student at the MPA program. I did my internship for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and we developed some mentoring products to help underprivileged people. My pilot really was centered on refugees, so I did go and reach out to the Swahili branch over there that has mostly refugee families. I went back to help, because I’ve been through that. I felt like I could have an impact, understanding what they’re going through. It was painful sometimes though because it would bring me back to the memories of what we’d been through when we were in Belgium, newly arriving there.

I was also a refugee in America, after Hurricane Katrina, when my husband and I first came to America and were living in New Orleans. Being a refugee a second time and seeing how organizations like the Red Cross and other grassroots organizations helped people—that was really what made me decide to go back and do my MPA degree at BYU. So that’s how I ended up doing all these things and when the Spirit prompts me, I just do it. I don’t know if I can live differently now than living a service-driven life. It’s the Spirit that talks to me, the same Spirit that talked to me when I was in Rwanda and told me, “You’ll be fine.” The same Spirit that talked to me when 25 years later when we were praying for my father, “Pray at this moment to remember him.” You know, the Spirit of revelation that we all have.

I feel like it’s the least that I can do after being saved from the war. So many people died, I can tell you, Meredith, you have no idea. In vain. Kids, families, women. Who am I? I have this life and I don’t want to spoil it if I have a possibility of blessing someone else.

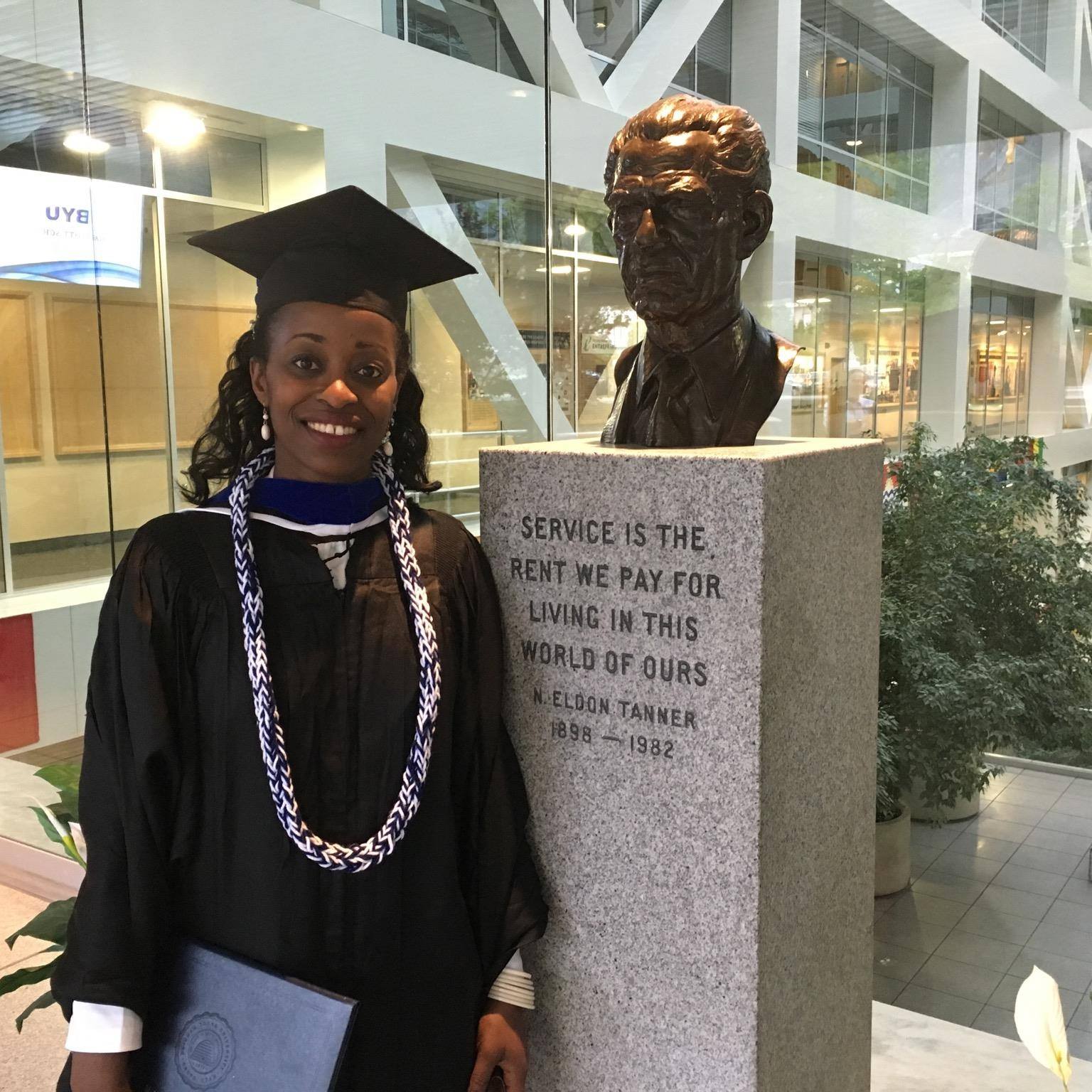

Yvonne’s graduation from Brigham Young University’s MPA program

That is very powerful. Ngoma Y’Africa tells stories through dance and music—what role have dance and music have played in your life through all these transitions?

Boy, that was therapy for me. Remember I told you how depressed and damaged I was, and how I was really traumatized from the war? That was the only thing that made me happy, when I was dancing. That would take me back to when my dad took us to his village, how the kids would come running, and dancing all the time and clapping. Some of the songs we used to sing, actually, came from villages of those people who were in Belgium as refugees, and some were from my father’s village and some of the songs really would just remind me of that time of innocence, the time of happiness in Rwanda. When we arrived in Belgium, we went to a dance group about the same as Ngoma, a cultural group from just Rwanda this time. I was a dancer from age fourteen, that’s about when the group started, until I left Belgium and I had already formed my own group when I was nineteen. That one was comprised of young people. Ever since then I realized that was a therapy for me. Remember I told you we never would consider seeing a therapist in our culture? So dance was my therapy. In fact, I realized in the African culture people sing and dance all the time. For any occasion. If a kid is born, if there’s a wedding, if there’s a graduation. Really, seriously. It’s part of what people do every day. All those events would culminate into a dance or a song of happiness and joy.

That’s really what helped me to cope during those years. Ever since, everywhere I’ve been, I’ve duplicated that. I find a space that I have to express myself and just forget about my troubles and my problems through dance. From Belgium to when I came to America, and the very first time we came to Utah in 2005 after Hurricane Katrina I had to find a space. Then I met a lady from Michigan, an African-American, who was like, “Hey! I love African dance. I love African culture. Are you interested?” At that time I was a stay-at-home-mom, bored to death, and I couldn’t do anything else, so I started that group with her when I was pregnant with my second one, and we used to help these kids who were adopted by Utah families, to teach them about their culture and where they’re from.

Yvonne during her time in graduate school.

There’s something about keeping your identity. If those kids, who leave their culture, have a space like that, it helps them to be accepting of who they are—ultimately happier people, and less dangerous to the society. Does it make sense? But the other way around, if they don’t accept their identity, they will identify themselves with a gang or whatever the TV portrays as the best person nowadays. So for us, it was also a safeguard in Belgium to be part of a dancing group. That’s what I wanted to offer to anyone when I started Ngoma. And we’ve been able to impact refugee kids who are in Utah County to come and have that space too.

It’s interesting to see what they go through, it’s the same as we did as teenagers in Belgium. It’s like “Oh, who am I? Who am I?” And then when they get there it’s like, “Oh, ok! I guess these are my roots.” I’m grateful I was able to do that in Belgium because I don’t think I would be here right now if I wouldn’t have been able to express myself through dance and discover that I can be a happier person and I can be confident, I can be a leader, I can be useful, and whatever talent I have can be useful to other people because they’re happy when they see me. And above all, in that group in Belgium, we used to do humanitarian service too, and that was a way to give back. That is something that was dear to me too because there were refugee camps in Congo when we arrived in Belgium, and most of my extended family were still alive in those camps. So we used to send back books and clothes and stuff like that. That was also a good way to feel like we were useful and helping those we left behind.

I have to dance to feel healed. And through the dances we do we also connect. There’s a lot of meaning. For example, in Rwanda and in many African countries, we have dances that are tied to a rite of passage like maybe from young woman to womanhood. There’s a whole education and learning tied to it and so all those different movements we do really have an educational meaning and a spiritual connection to it as well. There are some movements that are praising God. We used a lot of those in Be One because they were dances of worship and gratefulness. So yes, we dance with our body, but we dance with our heart and spirit.

Yvonne Baraketse

Your group performed in the Be One Celebration?

Yes, we did. I choreographed the African scene and the dance with Alex Boye. Our group was there and we recruited some other people in the community. My husband helped me very much with it. Really everything came together in a month. It was incredible how the Spirit just, from the moment it prompted me to do it, how I kept meeting people who were ready for that project. It came together really beautifully I think.

I was reading one day in the Church News, and they were talking about how they were going to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the priesthood being given to black people, and I was like, “What are they going to do exactly?” That was the first question that came in my mind. Because I told you I did my internship at the Church Office Building, so I know there’s not many people from Africa at the Church Office Building, let’s be honest. So I felt like, “I wonder if they need some help.”

I told you, at that time I was president of Ngoma and we had already been there for two years, a strong group. I felt prompted to call different people and I tried but couldn’t get anyone until one day, I woke up and I was like “I know somebody who works there. I’m going to email her.” And then I emailed her and then she’s like, “Oh I think this person is going to be the one you need to contact.” And when I contacted these people who were on the committee to prepare the show, they had just got out of a meeting and three people had mentioned my name in that meeting without knowing me, without knowing anything about me. So this person was like, “Oh! Something strange has happened. Yvonne just called!” and they said, “Yvonne who?” He said, “Yvonne, that everybody has been talking about, she just called.”

So that person reached back to me and he was like, “We’ve been looking for you!” and I’m like, “What? You’ve been looking for me? I’ve been looking for you.” That’s how we all connected, through the Spirit. Then we started going places and trying to recruit people. I spoke first to my husband about it—usually my husband just lets me do my projects, but he felt prompted that he should help. He used to conduct an orchestra in Africa when he was young, and he’s done a lot of different projects like that ever since, so he’s the one who put the music together and the whole sound that is in the background on the African scene. He was just incredible. Everything came together just last minute. The Spirit we felt when we were performing, it’s something I’d never ever felt in my life, ever, ever felt in my life. It’s just something you do once in a lifetime. I feel I’ve accomplished something great.

The Baraketse family after the Be One Celebration performance

I have no African background and I’ve never been to Africa, but I felt so much joy watching that performance; I really felt the Spirit. So, thank you for what you contributed. Yvonne, is there anything else that you’d like to share?

The Plan of Happiness is real, but I will add that happiness is a choice. Happiness in life is a choice. Every day we have the chance to say, “I will wake up today and make a useful, fruitful day. I’ll make a little difference today.” Or we can choose to be oriented on ourselves and worry about our own little problems. What I’m trying to say is every day we can really make a difference if we look for opportunities and listen to the Spirit. Can you imagine if the whole wide world had this mindset—how different this world would be?

At A Glance

Name: Yvonne Baraketse

Age: 38

Marital History: Married

Children: Hilarion (15), Eloha (13), Amani (7)

Occupation: Educator

Convert to Church?: Yes, August 11th , 2001

Schools Attended: Brigham Young University and Western Governors University

Languages Spoken at Home: French and Kinyarwanda

Favorite Hymn: I know That my Redeemer Lives

Website: https://ngomayafricacultur.wixsite.com/ngoma

Interview Produced by Meredith Marshall Nelson